Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love by telling your friends to sign up here and hitting the heart-shaped like button on this email.

Have you tried cutting your own hair, or made someone you live with cut it? Reply to this email or write to oversharingstuff@gmail.com with photos and a brief note about how it went to be featured in Overshearing, my new section on quarantine haircare.

Some housekeeping: a couple of you noticed Oversharing has comments now (and commented!). This is an experiment. I am generally skeptical of internet comments but also have faith in the good readers of Oversharing to maintain a friendly/civil level of discourse. If this doesn’t prove the case, I will disable commenting.

Taken out.

Uber is reportedly in talks to acquire Grubhub as soon as this month:

(Bloomberg) -- Uber Technologies Inc. has made an offer to acquire Grubhub Inc., in a move that would build out its food-delivery platform even as it shutters parts of its own service abroad, according to people familiar with the matter.

The companies are in talks about a deal and could reach an agreement as soon as this month, said the people, who asked not to be identified because the matter isn’t public. Deliberations are ongoing and talks could still fall through, the people said.

Investors love it. Grubhub gained as much as 38% the day the news broke, closing up 29% to $60.39 a share. Uber rose 2.4% to $32.40, never mind that the stock price of an acquiring company typically falls ahead of a deal on various investor concerns, for instance, that the company is overpaying, the acquisition is a bad fit, or that the need for a deal signals some weakness or inability of the acquirer to grow its business.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Grubhub asked Uber to pay 2.15 of its shares for each of Grubhub’s in an all-stock deal, a price Uber rejected as too high. The two companies are now considering a deal that would value Grubhub at around $6 billion. Uber announced yesterday that it is offering $900 million in bonds, the proceeds from which it plans to use for “working capital and other general corporate purposes, which may include potential acquisitions and strategic transactions.”

Grubhub and Uber look like a good fit. Investment firm Cowen suggested in a research note that only 38% of Grubhub monthly active users also use Uber Eats, meaning Eats could gain many new customers from a deal. Uber is accelerating its push into delivery of all kinds as the coronavirus batters its rides business, so gaining those customers is undoubtedly of interest. Grubhub is also dominant in US markets where Eats is weaker, according to data from research firm Second Measure, most notably New York City, Boston, and Grubhub’s home city of Chicago.

After a mid-2010s boom in food-delivery apps, consolidation has defined the past year. Uber refocused its Eats strategy on markets where it can be the no. 1 or no. 2 player, then pulled Eats from South Korea and sold it to Zomato in India. In January, Uber and DoorDash reportedly held merger talks at the urging of their common investor, SoftBank. Last week, Uber shut Eats in seven more markets and transferred it to subsidiary Careem in the UAE. Elsewhere, Amazon closed its restaurant delivery business and invested in Deliveroo (recently cleared by the UK competition authority); Deliveroo exited Germany. Just Eat merged with Takeaway.com, which previously acquired Foodarena and Delivery Hero’s Germany operations. Glovo pared its markets. Postmates, which filed confidentially but never publicly for an IPO, reportedly explored a sale to Uber or DoorDash last summer as an alternative to going public.

Grubhub has been rumored to be exploring a sale for some time. The Journal reported in January that Grubhub was considering “strategic options including a possible sale” as competition intensified in the food delivery space. In February, CEO Matt Maloney said on Grubhub’s Q4 earnings call that “industry consolidation could make sense, and like any responsible company it is something that we are always looking at.”

Grubhub was early to the food delivery game and unlike its VC-backed competitors, it was consistently profitable. That its business model worked should have given Grubhub a leg up, but what it actually meant was that the company was playing a different game from competitors bloated with venture capital and untethered to things like profit and unit economics. At a dinner in New York I attended in April 2019, Maloney griped that Grubhub could have huge growth like DoorDash if it also had $1 billion a year from “Uncle Masa” to spend, and he was probably right. Capital matters. Grubhub ran a financially sound business for public market investors who expected quarterly profits, even as its industry became increasingly detached from financial reality, guided by private investors with a growth-at-all-costs mindset. The market has finally started to rationalize, but for Grubhub the irrational exuberance died too late.

Frustrated by We.

After two years of renting the same dedicated desk at a WeWork in Washington, DC, Lisa Kaneff decided to make her month-to-month contract an annual one last November. Going annual kept her rent at $450 per month, or $13.49 off the new monthly rate. Kaneff, 38, a freelance copywriter, had met friends, clients, and her partner through the WeWork. She sat at a pod of four desks, in a glass-enclosed room affectionally dubbed the “fishbowl.” “The space really meant a lot to me,” she said.

Five months later, Kaneff was clearing her things from the WeWork desk as the coronavirus pandemic swept around the world. On March 30, the DC mayor issued a stay-at-home order that said residents could leave home for only essential activities, travel, business, and exercise. That meant Kaneff couldn’t go back to her desk even if she wanted to. But WeWork kept charging her $450 a month for the space. After Kaneff contacted WeWork repeatedly to ask for rent relief, the company offered to defer her rent for two months and distribute it over the remainder of her contract.

Quarantine is a bad time to be an office rental company. It’s also a bad time to be renting from one. Kaneff is part of a group of 20-some WeWork members in several US cities that recently threatened WeWork with legal action (arbitration, because WeWork has its members waive their right to class action, of course) unless the company stops charging fees to tenants who are legally barred from their offices and returns fees already paid under such circumstances. A letter from Manhattan law firm Walden, Macht & Haran claims the combination of the pandemic and government stay home rules has made WeWork’s membership agreement “valueless” to members, who shouldn’t have to pay fees. (In legal jargon, this is known as “frustration of purpose.”)

“WeWork continues charging these members full monthly fees and refuses to offer concessions or compromise,” the letter states. WeWork declined to comment.

On the other side of tenants resorting to threatening legal letters are WeWork’s month-to-month members, whom the company is desperately courting to stay. Bloomberg reported in late March that WeWork had offered some tenants half off their rent if they agreed to sign on for several months. WeWork offered free rent for the month of May to at least one month-to-month dedicated desk member at the same location Kaneff works from, according to an offer document she shared. More than half of WeWork members were committed for at least a year as of June 30, 2019, the company said in its IPO filing, but 28% were month-to-month. I’m willing to bet a lot of those monthly renters are cancelling right now, or already have.

Companies like WeWork are often called “flex office providers,” but flexibility isn’t a great business model in a pandemic. And so WeWork is doing its best to woo flexible tenants into less flexible arrangements, while keeping members in longer-term contracts locked in. WeWork has its own bills to pay and its payment of them has already been spotty, causing bonds backed by those payments to tumble. It recently cut more jobs, after previously laying off 250 people in March and 2,400 last year. Meanwhile, WeWork co-founder and former WeLeader Adam Neumann is suing chief WeWork backer and believer SoftBank for scuppering a $3 billion tender offer to shareholders, who of course include Neumann.

It’s unclear how far Kaneff and the others will get with their legal action. Kaneff’s contract, for instance, includes an “extraordinary events” clause that says WeWork isn’t liable for “any delay or failure to perform as required by this Agreement as a result of any causes or conditions that are beyond WeWork’s reasonable control,” a description that would seem to encompass a global pandemic, but I’m not a lawyer. In any event, the real risk to WeWork isn’t the arbitration, it’s that month-to-month tenants—roughly a third of members—flee, while the 54% who are locked in for at least a year become so embittered toward a company that refuses to help them out that they also ditch their leases as soon as possible and never come back.

Scooters!

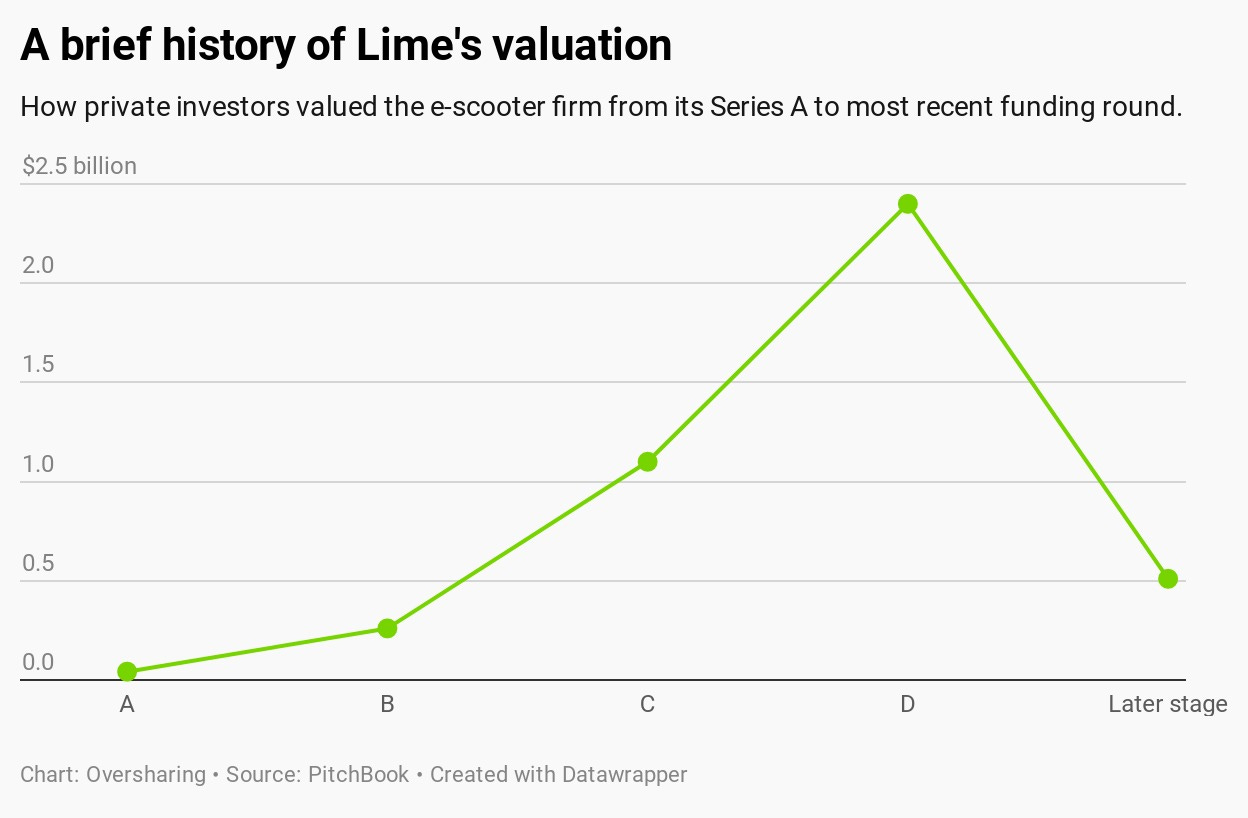

Uber led a $170 million rescue round into Lime at a $510 valuation, a massive haircut—which, let’s be real, we could all use after months in quarantine—from the $2.4 billion valuation Lime raised at in April 2019. Uber, which already owns a majority stake in Lime, will have the option to buy the company at a specific price between 2022 and 2024, The Information reported.

The deal gives Lime a chance to “fight back,” Wayne Ting, the former head of global ops who Lime recently promoted to CEO, told tech site Protocol. “This funding is going to be sufficient for us to weather the downturn and come back and compete and bring micromobility to more cities, which, especially because of COVID-19, is more needed today and more necessary today than ever before,” he said.

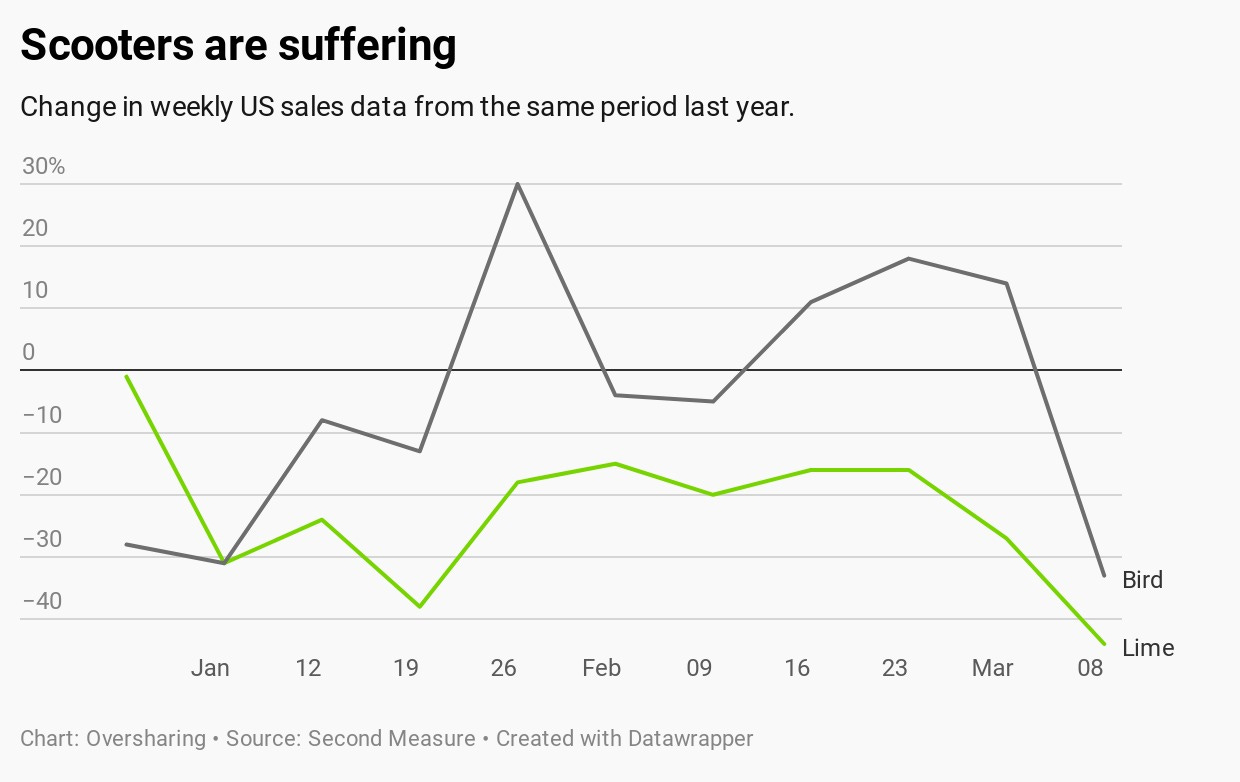

It is unclear who Lime is fighting back against… the coronavirus? Cities? Itself? Lime has already ditched a lot of markets—Santa Monica, Atlanta, Phoenix, San Diego, San Antonio, Bogota, Lima, Rio de Janeiro—and laid off about 200 people this year, but the business model was troubled before then. The unit economics of shared scooters remain questionable, a weekly subscription service failed to juice Lime’s business, and Covid-19 seems liable to kill it off. The week of March 9, Lime’s US sales were down 44% from the previous year, according to consumer purchase data from Second Measure, a worse plunge than competitor Bird took.

As part of the deal, Uber is offloading its Jump bikes and scooters business to Lime. Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said on the company’s Q1 earnings call on May 7 that transferring Jump to Lime, thereby taking costs associated with the business off its balance sheet, would result in $160 million in annual EBITDA savings, plus “meaningful CapEx savings.” At Uber’s annual shareholders meeting four days later, he described it as a “merger and a divestiture.”

Buying Jump in April 2018 was Uber’s first acquisition under Khosrowshahi, who by then had brushed off the ashes of the Travis Kalanick era. Uber framed the purchase as part of its mission to get personal cars off the road, reducing congestion and parking spaces. Jump and its founder Ryan Rzepecki were well known in the micromobility community, and Rzepecki’s nerdy enthusiasm for bikes made him a welcome contrast to the stereotypical startup founder.

Two years later, Uber’s dream of being a greener, multimodal trip platform has faded. Mounting evidence shows that ride-hail services worsen congestion, rather than ease it. Mobility services are costly to operate, and their business models still unproven. Jump remained a vanishingly small part of Uber’s business, according to the Googleseque “Other Bets” segment of Uber’s financial statements. In the latest quarter, Other Bets—which consists mainly of e-bikes and scooters—lost $63 million in “segment adjusted EBIDTA” on $21 million in gross bookings. That was less than 0.2% of bookings generated by the coronavirus-diminished rides business, which still turned a profit on an adjusted basis, and it makes the $85 million Uber reportedly put into Lime’s latest round seem like a bargain. Uber hasn’t necessarily given up on the multimodal future, but for now it seems wise to let someone else figure it out.

This time last year.

Uber drivers strike ahead of Uber IPO

Overshearing.

Jen Williams, a freelance UX designer in Minneapolis, gave her wife a buzzcut last week after brown roots started peaking through her platinum-blonde pixie cut. Jen writes:

My wife is naturally a brunette, and right before quarantine, she had her stylist color her pixie cut an awesome platinum blonde. Looked fantastic...until it didn’t. Apparently she’s always had a bucket-list item to shave/buzz her head (but this was the first I’d heard of it!), so she borrowed our daughter’s boyfriend’s dad’s Wahl clippers, and asked me to give her a buzz cut. I was less than enthused by the idea, but I also agreed that her brown roots and platinum ends were getting pretty ugly, so I gave it my best shot. Both she and I love the result—I think she looks super badass. :)

Other stuff.

Uber cuts 3,700 jobs. Online used car seller Vroom files confidentially for IPO. Driverless car startup Zoox is for sale. UK plans £250 million investment in cycle lanes, fast tracks e-scooters. Uber CEO outlines health benefits for drivers, after California sues Uber and Lyft for misclassifying drivers as contractors. Intel buys trip-planner app Moovit for $900 million. SoftBank-backed Opendoor resumes operations. DC temporarily caps food delivery commissions. New York City caps total food delivery fees at 20%. Chicago will require food delivery apps to disclose all their fees. Online grocer Ocado stopped selling bottled water to deliver to 6,000 additional homes. Put restaurants outside. How bike lanes boost local businesses. Coronavirus has shown us a world without traffic. Airbnb’s “talent directory.” “Demand for Instacart has risen to a level investors didn’t expect to see before 2025.” Travis Kalanick buys $43 million Bel Air mansion.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Stay safe in these crazy times! Send tips, comments, and Grubhub takes to @alisongriswold, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.

Oh and by the way: GREAT newsletter.

I will attempt to get my comment over the bar by inserting "Beyonce, kittens, sunrise over beach." (Perhaps my understanding of SEO is not fully mature.) I'd like to reiterate a question that has bothered me re micromobility (MM) for some time. (Before any Micronauts assault me, let me assure them I am not anti-MM!*) Why rent a scooter when you can just buy one? When do they become cheap enough and durable enough, maybe collapsible enough (to carry) so that one need not pay per use? I look at MM Nirvana (aka Copenhagen) and see shoals of bikes... but owned bikes, not rented? Just curious.

*Indeed I have my own MM start-up plan: we distribute pairs of shoes all across town. Approach a pair (lying on a sidewalk), scan their QR code, and don them: now you can micro-mobilize ( = walk ) all around town. No need to ever own personal footwear again!

I, perhaps inevitably, call it... Shoeber.

I am accepting investments in units of $50 mm (I am not greedy).