Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last week, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

I’m heading to Paris for work Wednesday through Friday, because a perk of being based in London is that Paris is quite close and going there is no big deal. I plan to test out all six bajillion scooters for the sake of journalism. If you will also be in Paris and would like to join me in this epic undertaking, or grab a scooter-free coffee, shoot me a note here or on Twitter.

“Uncle Masa.”

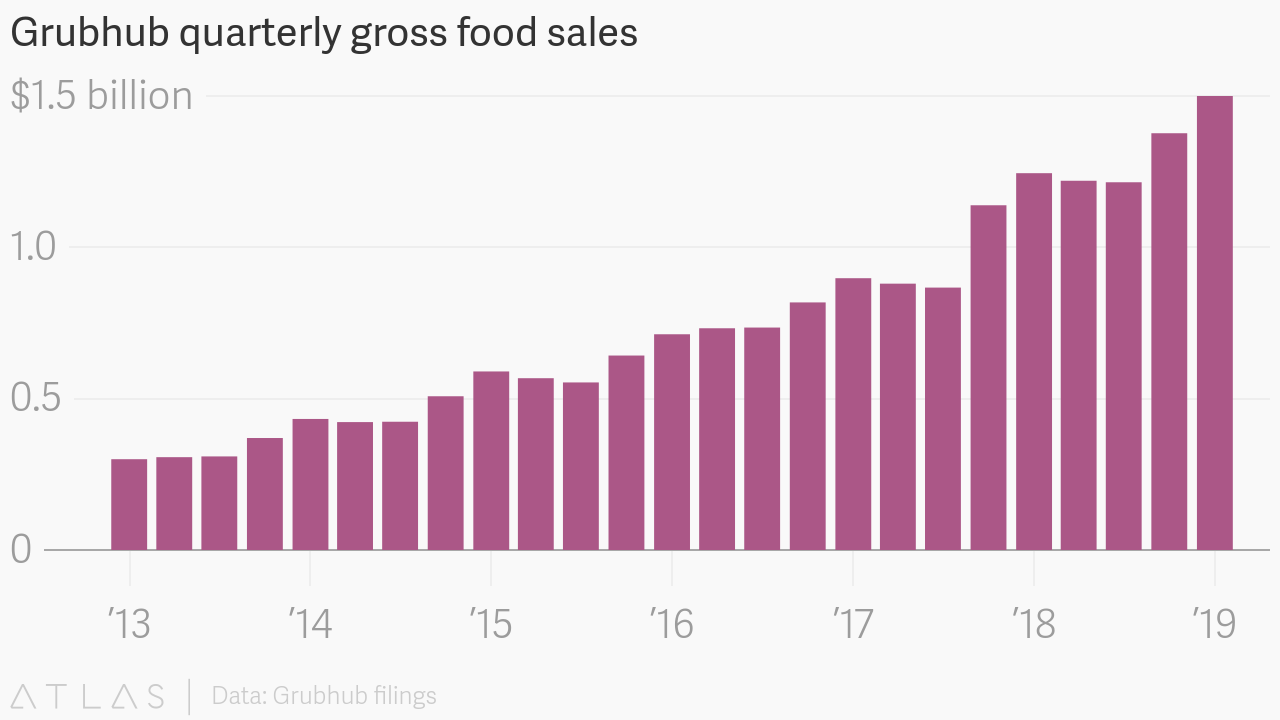

Grubhub, the longtime king of US online food delivery, fell to DoorDash in May, according to new credit transaction data from research firm Second Measure. DoorDash claimed 32% of sales that month among the food delivery companies Second Measure tracks—see chart below—compared to 31.7% for Grubhub. Uber Eats trailed in third with 19.7% of sales (a bad sign considering how much Uber spent on Eats driver incentives in the first quarter), followed by Postmates with 10.2%. Almost everyone’s sales are still growing overall with the market, but DoorDash is taking a bigger slice of the proverbial pie.

DoorDash has over the past year pulled away from a pack of Silicon Valley startups jockeying to win the food delivery space. It helps that DoorDash is the definition of richly funded. It’s backed by $2 billion in financing from investors including Softbank, of course, and was last valued at $12.6 billion, nearly double the $6.6 billion market cap of publicly traded Grubhub. DoorDash isn’t profitable, while Grubhub is.

This funding is a sore point with Grubhub execs, who have tired of hearing about DoorDash. Both DoorDash and third-party data providers like Second Measure were the subject of much conversation at a Grubhub dinner I attended in New York City in April. Grubhub CFO Adam Dewitt said DoorDash’s story was “aided by some grossly incorrect third-party credit card panels.” Grubhub CEO Matt Maloney called Softbank CEO Masayoshi Son “Uncle Masa” and said Grubhub could also post huge growth numbers if it were willing to spend $1 billion a year on subsidies for diners and restaurants. “Sometimes you can get free money and sometimes you can’t,” Maloney said. “The current practices have to break when there’s a cost of capital.”

Food delivery, as we’ve talked about before, is a tricky business, without much money to go around for all the parties involved. Companies like DoorDash make money not only from the fees their customers pay, but also from the cut of revenue they take from the restaurant on the sale side. As anyone in the restaurant business knows, margins are already thin enough without having to make room for a delivery startup.

Some of the biggest chains are now pushing back. “McDonald’s Corp., Applebee’s and Cousins Submarines Inc. are among chains negotiating to pay lower commissions and asking their delivery partners to spend more on marketing and promotional discounts,” the Wall Street Journal reported June 23. The irony is that these big chains are likely already getting a better deal. Uber, for instance, noted in its IPO filing that it charged “a lower service fee to certain of our largest chain restaurant partners,” which it said sometimes led to Uber losing money on the transaction.

Chains can extract better terms because they make up a bigger chunk of sales for delivery platforms. Smaller restaurants have the same problems with delivery companies but not nearly as much bargaining power. Take Mission Pie, a local favorite in San Francisco whose owner said she couldn’t afford to pay a 25% to 30% commission to delivery services, because it would eat up her entire profit margin. Last week, Mission Pie said it would close in September after 12 years in business, faced with the “extraordinary increase in the cost of living in the Bay Area.” Profits declined even as the cafe got busier, the cafe’s founders wrote in a Facebook post, adding that the options they considered for expanding proved to be bad for business. “We’re looking at you, delivery apps,” they wrote.

Scooters!

Nashville mayor David Briley would like to ban them after a man died riding one. Brady Gaulke, 26, died in May after being struck by a vehicle while riding a Bird scooter. Police said Gaulke made an improper turn onto the road from the sidewalk around 10pm on May 16, when he was hit by a Nissan Pathfinder. He died of his injuries three days later. Police later concluded that Gaulke “operated a Bird scooter in a reckless manner while under the influence of alcohol.” No charges were filed against the Nissan Pathfinder driver.

Gaulke’s girlfriend of four years set up a GoFundMe to raise money for his medical expenses, memorial service, and a foundation that raises awareness around brain trauma. The GoFundMe page, which at last count had raised $13,910 of its $15,000 goal, also called for Nashville to “ban these awful motorized vehicles in our cities.” It included a link to a petition calling for the mayor and city council to ban electric scooter companies that as of today had more than 2,700 of its goal of 5,000 signatures.

On June 21, Briley recommended the metro council end an e-scooter pilot and pass legislation to remove scooters from city streets and sidewalks. “We have seen the public safety and accessibility costs that these devices inflict, and it is not fair to our residents for this to continue,” Briley tweeted, adding that scooters could return in the future under a more rigorous permit process and “with strict oversight for numbers, safety, and accessibility.”

Nashville’s metro council is scheduled to take up Briley’s proposed ban on July 2. In the meantime, the city’s e-scooter companies—Bird, Bolt, Gotcha, Lime, Lyft, Spin, and Uber—are continuing to operate normally. Bird was quick to point out that Briley can’t single-handedly shut down scooters in Nashville. Bird also said it is on track to pay out more than $1 million in wages to locals who charge scooters in 2019 and that banning scooters would put all these scooter-chargers out of work. Uber used to brandish a similar line about drivers being hurt and out of work when cities threatened to ban or restrict its operations. Bird was started by a former Uber guy, so it’s not surprising that Uber tactics remain its M.O.

Meanwhile, in New York, electric scooters and electric-propelled bikes could soon be made legal in the state, if not yet New York City, which would have to nix its own rules prohibiting their use. The agreement clears the way for companies like Bird and Uber-owned Jump Bikes to start service in the state, the result of roughly half a million dollars in lobbying by scooter companies so far this year. More importantly, it brings the city one step closer to permitting so-called throttle electric bikes that don’t require the user to pedal and which are primarily used by food delivery workers. The city has aggressively ticketed these workers and at times confiscated bikes in a crackdown that seems to ignore the yuppie millennials who ride equally illicit scooters around.

Backpedaling.

Chinese bike-sharing startup Ofo has “basically no assets,” a Chinese court ruled June 17, and no ability to pay its debts to suppliers and users. Founded in 2014, Ofo raised more than $2.2 billion from backers including Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba and ride-hail company Didi Chuxing to popularize dockless bikes in China, then burned through it in a fierce, costly battle reminiscent of the war between Uber and Didi. Ofo’s banana-yellow bikes were plagued by vandalism and theft and discarded by the thousands in piles that became known as bike graveyards. Ofo briefly expanded to the US before shuttering most of its operations there last summer.

Supplier Tianjin Fuji-Ta Bicycle sued Ofo this year in an attempt to recover roughly $36 million. Ofo has also stiffed nearly 12 million customers who put down small deposits to use the service and have requested refunds totaling $170 million. The Chinese court noted that Ofo’s bank accounts either have a zero balance or are frozen and that it has no other valuable assets, because it is apparently that easy to get rid of $2.2 billion.

The story should be a cautionary tale for the Silicon Valley ecosystem and investors who pour funds into money-burning startups in the hopes that one of them will turn out to be the next Uber. Also, if your company’s product is ever trashed so intensely that the rubbish gets nicknamed a graveyard, maybe consider that something has gone horribly wrong.

New hires.

Same-day delivery company Deliv is getting ahead of California’s proposed changes to employment classification by hiring its workers. The company said June 18 it would form a subsidiary, Deliv California, Inc., to hire workers in the state who are currently independent contractors as employees, beginning in Sacramento and rolling out across California by the end of August.

As employees, Deliv workers will get an hourly base wage plus $0.58 reimbursed per mile (the federal rate as of July). They will also receive the hallmark benefits of employment: workers’ compensation and unemployment, paid sick leave, a retirement plan, and health insurance. Deliv will subsidize health care for couriers working 30 hours or more a week, and give other workers access to insurance plans at discounted group rates. For Deliv, making workers employees also means it can manage and train its workforce better than it could with independent contractors.

Deliv is fairly well suited to this change. Its workers already sign up for shifts to make scheduled deliveries, unlike workers for companies like Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Postmates, who sign on and off as they please and, when on, respond to immediate consumer demand.

Deliv will be an interesting litmus test of how smoothly workers can make the switch from contractor to employee. As California’s proposed changes have gained momentum, many gig companies have issued dire warnings about how classifying their workers as employees would destroy flexibility and limit potential earnings. It’s unclear how much of this is rhetoric designed to frighten workers vs. a legal or financial reality. Deliv’s new employees will be some of the first to find out.

This time last year.

Uber got its license back in London, also, Oversharing joined Substack 🎉

Other stuff.

WeWork sued by former execs for age, gender, discrimination. Presidio Trust rejects WeWork-led development proposal. Waymo partners with Renault and Nissan to “explore driverless mobility services” in France and Japan. Humanising Autonomy raises $5 million to work on driverless-pedestrian interactions. Female ride-hail drivers say companies fail them on sexual harassment. Uber driver sentenced for kidnapping female passenger. Lagos-based Max.ng gets $7 million for ride-hail motorcycles. Cairo-based Swvl raises $42 million for private bus service. Grocery outlet jumps 30% in trading debut. China’s favorite food delivery service worth more than its biggest internet search firm. European cities seek EU help against Airbnb. Uber clean air fee has raised £30 million. Number of US taxi drivers has tripled in a decade. Ampersands. Compost. E-unicycles. “There is no single source of truth for all businesses in all categories.”

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and your top Paris recommendations to @alisongriswold on Twitter, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.