Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from two weeks ago, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

The prom.

Uber Technologies Inc. plans to go to the proverbial prom this week, in an IPO that could value it between $80 billion and $90 billion, per the Wall Street Journal. As much fun as I’ve made of this particular Travisism, prom is actually not a bad metaphor for what’s about to happen. An initial public offering, like the prom, follows a period of great anticipation, excitement, and anxiety. It’s the natural ending of one phase and the natural start of another. Uber hasn’t really been a startup for a long time, but an IPO brings those startup days to both a formal and a symbolic end.

It’s also fitting that in the days leading up to its IPO, the Uber news cycle is being dominated by a global Uber driver strike. Drivers have gathered to protest Uber and its labor practices in Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington DC. Protesters are also reportedly convening in Australia, Brazil, Chile, France, Nigeria, and the UK, among other countries.

The strike has garnered a fair amount of Twitter buzz, with support from Bernie Sanders and Catastrophe co-star Rob Delaney, and been covered extensively online and on cable news. How the demonstrations are going is less clear. The New York Post, for instance, reported earlier today that the strike was a “flop,” with cars plentiful and surge pricing scarce (the actual strike was scheduled for only two hours, from 7am to 9am). In San Francisco, things are only just getting underway, with 12 hours of demonstrations starting at noon local time. In London, hundreds of drivers began protesting at 9am local time and marched through the city.

Collective action has largely eluded drivers over Uber’s 10-year history. Uber regards its drivers as independent contractors, and in the US there are no collective bargaining rights afforded to contractors. Early attempts at strikes by driver groups were easily broken up by the company, which could pull one of its many levers—surge pricing, promotions, and so on—to ensure a critical mass of drivers stayed on the road. Uber has aggressively fought a first-of-its-kind 2015 law in Seattle that gave local drivers permission to unionize. It preempted a similar effort in New York City by sanctioning the Independent Drivers Guild, a non-union driver advocacy group that helped organize the strike taking place today.

I took an Uber earlier today, which I suppose makes me a bad person, but I was in suburban Connecticut and needed a ride to the train station, and had no other options. My driver, a nice guy named Andre, said he’d only briefly heard of the strike from a family member who saw it on TV, but didn’t know any details of where or when it was happening, or what was expected of him. We chatted about what it’s like driving for Uber and Lyft, how rising gas prices have depressed his wages, and New York City’s effort to set a pay floor for drivers. Andre is hoping that once Uber goes public, it will finally get serious about giving drivers the recognition they deserve.

While an IPO seems unlikely to make Uber change its ways, it’s also hard to see what a strike accomplishes. The public pressure may last a few days, but sooner or later people need to make money and get places, and Uber for all its faults helps them do that. The company emerged not unscathed but intact from 2017, a year that makes today look like a comparative blip. More to the point, Uber counted 3.9 million drivers on its platform as of Dec. 31, 2018. Tens, even hundreds, of thousands of those drivers could go on strike before the impact was really felt.

Drivers are understandably angry that Uber employees are about to get rich while they get additional pennies per trip, yet the company is still hemorrhaging money, and it’s unclear whether Uber could pay drivers more even if it wanted to. In New York City, where minimum driver pay rules took effect in February, the company paused new driver signups and said in an amended IPO filing that the rules “had a negative impact on our financial performance” in the first quarter. Uber, as we talked about before, has also basically admitted that it thinks of drivers as comparable to restaurant service workers, and that taking a bigger share of the fare is its path to profitability.

The tough reality is that Uber isn’t designed for workers to make good money, whatever it may have told them in the past, and it probably never was. Ahead of its IPO, no amount of striking will change that.

“Bending cost curves.”

Lyft Inc. is no longer a startup but it still loses money like the best of them. Lyft lost $1.1 billion in the first quarter of 2019 on $776 million in revenue, a hit it attributed to $894 million in stock-based compensation and related payroll tax expenses triggered by its March IPO. The company lost $234 million on $397 million in revenue during the same period in 2018.

Lyft said active riders, or the number of people who took at least one ride on a Lyft service during the quarter, increased by 46% year over year to 20.5 million, and that revenue per active rider jumped 34% to $37.86. Those rider numbers were likely boosted by the $275 million Lyft spent on sales and marketing in the first quarter, or $230 million excluding the portion related to stock-based compensation, up from $169 million in the first quarter of 2018.

Despite that sizable increase in marketing, Lyft chief financial officer Brian Roberts noted “competitive pressure in terms of rider incentives has recently receded” and said the industry was “becoming increasingly rational” on pricing. Lyft chose not to report gross bookings, a measure of the total dollar value of sales made through its platform that Uber has long shared with its investors.

Lyft’s first-ever quarterly earnings report as a public company made clear that it prefers to focus on its adjusted net loss, which strips out most of those stock-based compensation costs and related payroll tax expenses. By this measure, Lyft lost only $212 million in the first quarter, a lot better than $1.1 billion and also an improvement from an adjusted net loss of $228 million in the first quarter of 2018.

Whether Lyft should strip these costs out is a separate question. NYU finance professor and valuation guru Aswath Damodaran has long critiqued this treatment of stock-based compensation, arguing that stock-based compensation is how companies pay and retain employees they otherwise couldn’t afford. Here is Damodaran discussing a similar move by Twitter in 2014:

Attempting to give Twitter, the benefit of the doubt, the rationale for adding back the expense to get to adjusted EBITDA is that it a non-cash expense (though I will take issue with that claim later in this post), but that cannot be the rationale for adding it back to get to net profit, since net profit is an accounting earnings number, not a cash flow. One possible explanation that can be offered (and it is a real stretch) is that Twitter views stock-based compensation as an extraordinary expense that will not recur in future years and that the adjusted net income should therefore be viewed as a measure of continuing income. I will believe this explanation, if I see Twitter stop using stock-based compensation, but I don't see how they can afford to. They have a lot of employees, some of whom are highly paid, and they cannot afford to pay them cash.

Asked by an analyst to discuss the company’s path to profitability, which remains tremendously unclear, Roberts pointed to a variety of customized accounting figures, including the improved adjusted net loss, while pointedly ignoring that $1.1 billion number. “We have teams across the company dedicated to initiatives that will help us grow more profitably in the core ridesharing business by both bending cost curves and increasing the efficiency of growth levers,” he said, a perfectly vague answer fit for a public company executive.

Scooters!

Over 936,110 scooter trips from Sept. 5, 2018, through Nov. 30, 2018, in Austin, Texas, an estimated 190 riders were injured, or about 20 per every 100,000 trips, according to the results of an “epidemiological investigation” released by Austin Public Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on May 1.

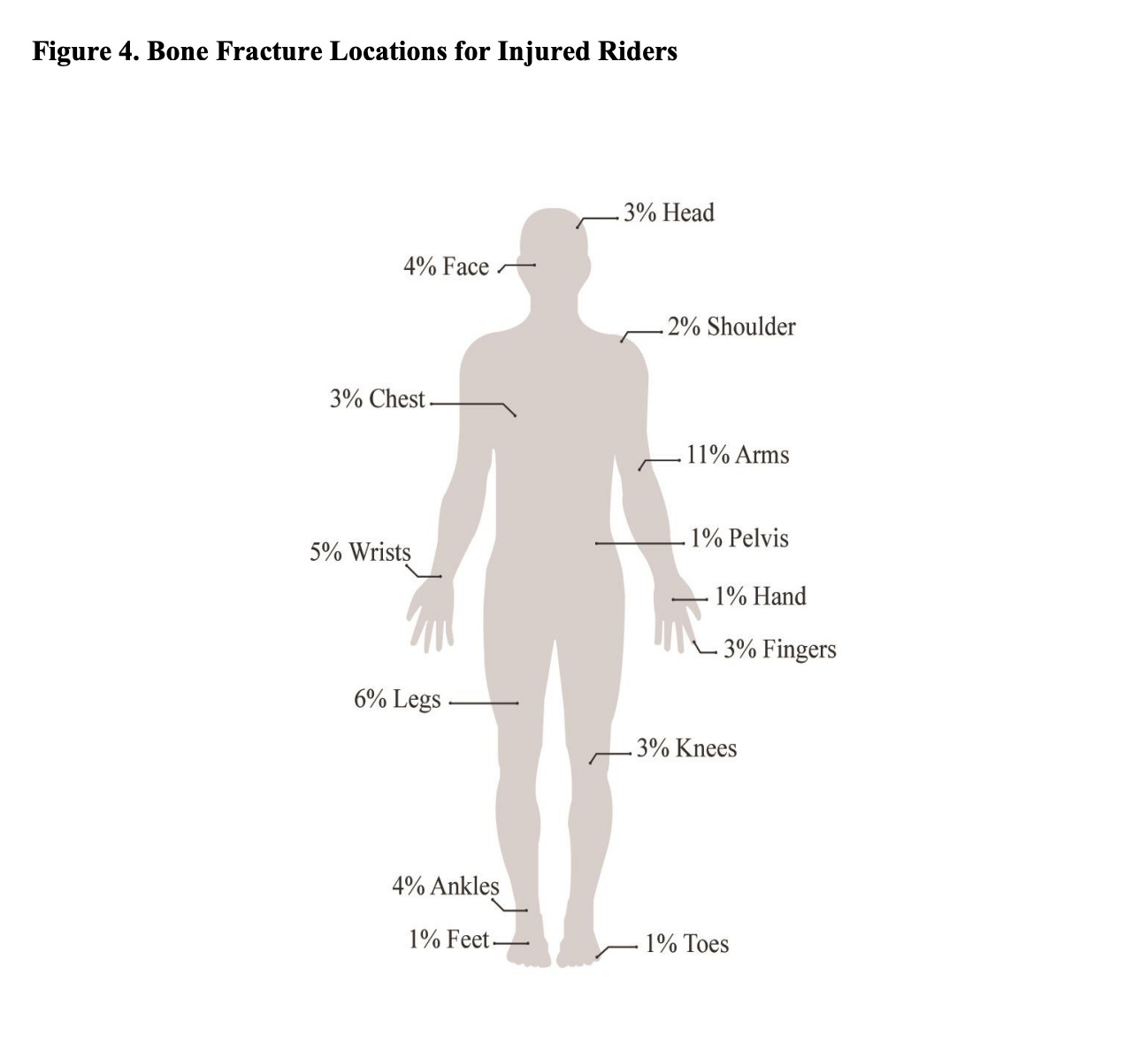

The study was the first in which researchers interviewed dockless e-scooter riders to learn more about the circumstances of their injuries. These circumstances tended to include riding on the street, going faster than expected, consuming alcohol, and perceived scooter malfunctions, like the brakes not working. About half of riders met the National Transportation Safety Board criteria for a “severe injury,” typically involving either bone fractures or nerve, tendon, and ligament injuries. Almost half of riders sustained some sort of wound to the head, with about 15% potentially suffering a traumatic brain injury such as a concussion.

Dockless e-scooters look like larger versions of the classic children’s toy, with their sleek designs and bright colors, but they go much faster on streets much busier than the neighborhood cul-de-sac. I recently tried one in Washington DC and was surprised by how fast 7 or 8 miles per hour feels—and most scooters go up to 15mph—when standing bolt upright on a narrow platform with only the handlebars to hold.

Scooter riders also don’t tend to wear helmets, as evidenced by the number of head injuries in the Austin study, and scooter companies have only tepidly encouraged helmet use among riders, with advisories in the app and the occasional offer to ship a free or discounted helmet to a customer’s home. Bird, for instance, says it will ship one helmet to each active rider for $9.99 to cover shipping, but what would the rider do with the helmet after that? Half the appeal of the scooter model is spontaneity; you are out for a walk and see a scooter, and grab it to accelerate your journey from point A to point B. It seems unlikely that the casual scooter rider would take to carrying around a helmet with them the same way a veteran cyclist might. Plenty more scooter riders probably never even consider that they should wear a helmet to go a couple miles on a device that resembles a toy they had as a child.

Since companies like Bird, Lime, Scoot, Spin, and Skip popularized dockless e-scooters last year, the devices have been linked to hundreds of injuries and a handful of deaths. In one of the latest tragedies, a 5-year-old boy died in late April after he fell from the Lime scooter his mother was driving and was hit by a car in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Scooters, of course, remain much safer than cars. There were 16.9 deaths from motor vehicle crashes per 100,000 licensed drivers in 2016 in the US, according to the latest data available from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. There were 1,418 injuries per 100,000 licensed drivers. Austin’s statistics aren’t exactly comparable, as they give injuries per number of trips rather than active riders, but they are an order of magnitude lower. In 2015, 818 cyclists died in motor vehicle crashes, making them 2.3% of all motor vehicle fatalities, and another roughly 45,000 were injured, according to NHTSA.

Is “safer than cars” good enough? Austin Public Health and the CDC say their study likely underestimates scooter injuries, as anyone who sought care at an urgent care center or doctor’s office, or didn’t seek care at all, wasn’t included. They suggest many of these injuries could have been avoided with greater helmet use, as less than 1% of riders were wearing a helmet when they were injured. And they clearly think scooters shouldn’t go so fast. Thirty-seven percent of riders attributed their injuries to “excessive e-scooter speed,” to which the researchers concede, “This perception may be true.”

WePO.

The We Company, yet another startup to distinguish itself by the tremendous amount of money it loses, has filed for an IPO. According to the Wall Street Journal, The We Company, formerly WeWork, in December filed confidentially for an offering, a move that “caught many observers and even some investors by surprise.” WeWork made its filing without the help of bankers, the Journal reported, an unusual move even for a self-proclaimed capitalist kibbutz, and perhaps part of the reason why the filing went undetected for so long (over at Axios, Dan Primack points out that no bankers means no leakers). Here is more from the Journal:

The public markets would mark a huge test for WeWork, which has long attracted scrutiny from landlords, analysts and many tech investors for its lofty valuation assigned by private investors, especially when compared with real-estate companies in similar businesses. WeWork is primarily focused on real estate, renting long-term space, renovating it, then dividing the offices and subleasing them on a short-term basis to other companies. Chief Executive Adam Neumann and his deputies have said investors should treat WeWork more akin to a tech company, pointing to its rapid growth and various services it eventually hopes to offer that cater to its tenants.

It is also aided by strong demand from a generation of young workers and large companies seeking hipper offices and which laud its avant-garde design and offerings like kombucha on tap.

I really hope kombucha is mentioned in the IPO filing.

This time last year.

“Earnings excluding gluten” and other suggested startup accounting schemes

Other stuff.

Uber’s Stunning Journey to a $90 Billion IPO Changed Transportation Forever. PayPal puts $500 million behind Uber. Goldman Sachs could see 12,000% return on $5 million Uber bet. In tight labor market, gig workers harder to please. Invest in the gig economy with this ETF. Waymo deploys self-driving cars on Lyft. The accounting practice that should raise eyebrows at Uber and Lyft. Wheely raises $15 million for luxury ride-hail app. Boston’s Logan Airport passes fee increases for Uber and Lyft. Bronx man sentenced to 39 months in prison for scheme to defraud ride-hail drivers. Can Uber Ever Make Money? Airbnb says no city makes up more than 1% of listings. Instacart adds new features to improve relations with shoppers. How much Americans spend on groceries every month. That time America almost banned chain grocery stores. Uber adds public transit ticketing to its app. Uber and Lyft “biggest contributors” to congestion in San Francisco. Whale With Harness Could Be Russian Weapon. Who Controls a Tech Company Once It Goes Public? Women’s health-care startup Nurx shipped returned drugs to customers. I Fell Out of Love With Microsoft Excel, Because Google Sheets Is Better.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and scooter injury reports to @alisongriswold on Twitter, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.