Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. Hope you are staying safe, healthy, and moderately sane.

Have you tried cutting your own hair, or made someone you live with cut it? Reply to this email or write to oversharingstuff@gmail.com with photos and a brief note about how it went to be featured in Overshearing, my new section on quarantine haircare.

Delivery time.

We talked last time about what Uber should do now: suspend all but essential rides and devote its resources to delivery. Yesterday Uber announced two new products along those lines, called Uber Direct and Uber Connect. Direct will let consumers place orders from retailers for delivery, such as over-the-counter medications and pet supplies. Connect is a courier service for Uber customers to send packages to friends and family members. Both Direct and Connect represent an effective revival of Uber Rush, the precursor to Uber Eats that Uber shut down in April 2017. (Uber folks, I am here to chat about delivery, or your home haircuts!)

The delivery opportunity is of course much bigger than Uber. With an estimated one-third of the global population on lockdown, services that deliver groceries, medicines, prepared food, and other essentials have never been in higher demand. Even Amazon is struggling to keep up with orders. It’s as though most of the world signed up for a one-month trial overnight.

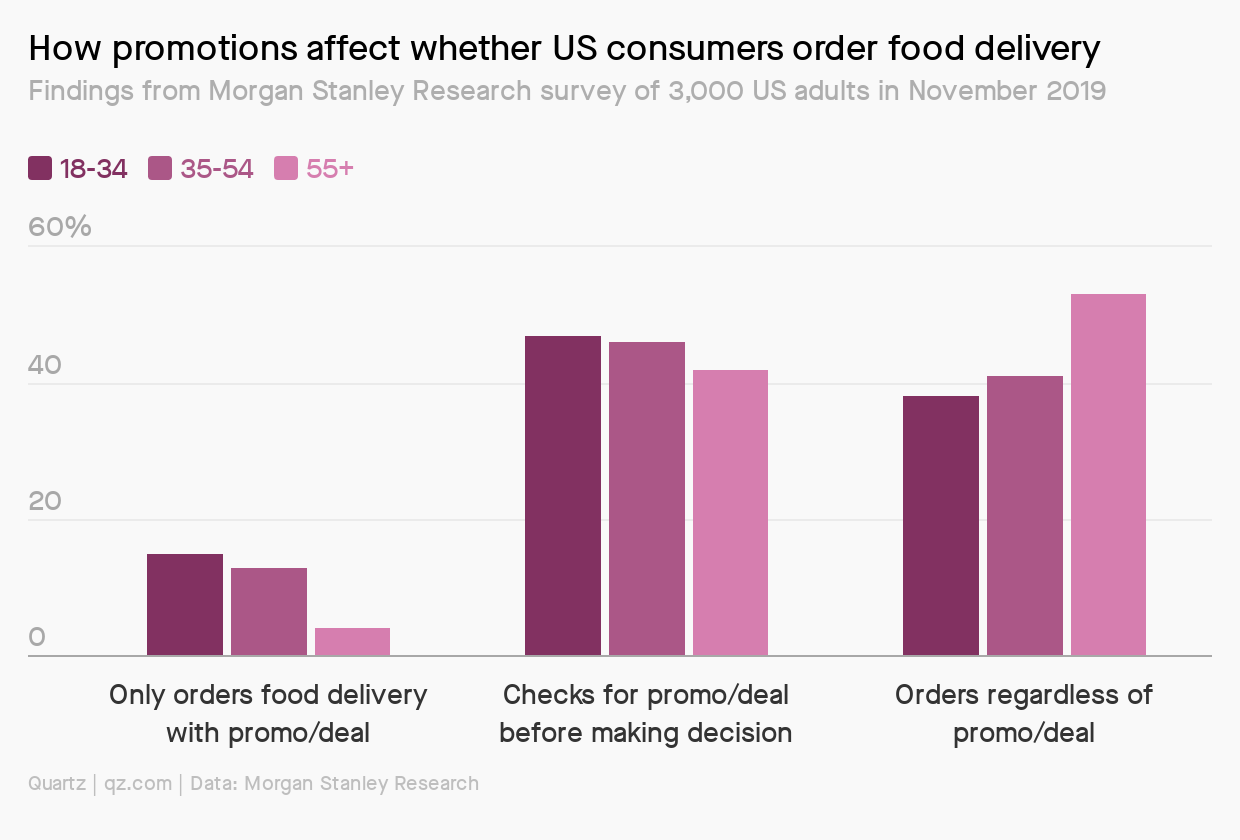

This unprecedented demand changes the delivery equation in several key ways. First, after years of promotions and subsidies to get consumers through the door, companies inundated with orders may now be able to charge the true cost of their service, fundamentally changing the unit economics of the business. Second, delivery is in high demand from merchants too. Shops and restaurants closed up by government-mandated quarantines, and groceries and pharmacies racing to expand their delivery options all need a last-mile partner that can make that happen, which gives companies offering that service more negotiating clout in any deals they cut.

The long-term question is whether demand for delivery spurred by the coronavirus will continue when, in the vague and distant future, the world returns to some degree of normal. Delivery companies have been handed an unprecedented opportunity, and how they perform now will determined whether their businesses are permanently altered as the virus fades into the background. I know, dramatic! I would tell you more, but instead will direct you to read all 2,800ish words I wrote on it for Quartz.

Union drive.

In December 2015, the Seattle city council passed an ordinance giving Uber drivers the right to form a union. It was a historic moment—the right to collective bargaining is traditionally reserved for employees, not independent contractors—but nothing ever came of it. The US Chamber of Commerce immediately sued Seattle on behalf of Uber and Lyft, Uber kicked off an enthusiastic union-busting campaign with unsolicited phone calls and a podcast (to be fair, who didn’t have a podcast?), and the law has been mired in litigation ever since.

At some point it became clear that the union law may never see the light of day, and the city turned to other options. Last fall, mayor Jenny Durkan introduced a “Fare Share” program to create a minimum wage for ride-hail drivers, who as contractors also aren’t protected by federal, state, or local minimum wage laws. Durkan’s proposal was modeled on similar pay rules developed and implemented by New York City, and the Seattle City Council passed it unanimously in November.

Longtime readers of Oversharing know that I am a fan of the Parrott-Reich pay rules for New York City ride-hail drivers, which are extremely clever, if also imperfect. One reason I like the Parrott-Reich solution is because it neatly sidesteps the issue of whether Uber and Lyft drivers are employees. A decade of debate over this question has brought little relief to workers, and clarified only that the matter is a political and legal quagmire unlikely to be resolved any time soon. The wage rules, by contrast, manage to actually address a problem—setting a pay floor for drivers who aren’t protected by minimum wage laws—without getting bogged down in the employment classification debate.

If pay floors prove effective for improving the lots of Uber drivers in New York and Seattle, it’s not crazy to imagine other local and state governments starting to look at more targeted fixes to protect their ride-hail drivers and gig workers. While this might not satisfy labor groups that want to see gig workers declared employees, or companies that would like to see them enshrined as contractors, it could do a lot more to tackle the realities of gig work in the US, and perhaps even obviate the employment classification debate.

Already, the wage and benefit plan approved by Seattle, which kicks in July 1, seems to have done just that: the US Chamber of Commerce, Uber, and the city of Seattle recently agreed to dismiss the lawsuit over the unionization ordinance, and focus on implementing the Fare Share plan instead.

Flex offices.

Quarantine is not a good time to be renting out offices.

WeWork skipped April rent payments at some US locations as it attempts to renegotiate leases and has another round of layoffs planned for May. (WeWork cut 2,400 jobs last fall after its IPO collapsed, and laid off another 250 people in March.) Knotel, another flex office provider, laid off 30% of its 400 employees, furloughed another 20%, and reportedly plans to return around 1 million square feet, or 20% of its portfolio, to landlords. Women’s social club The Wing laid off the majority of its workforce (The Wing had about 150 full-time HQ staff and 300 hourly employees as of mid-March); flex office firm Industrious laid off 90 employees and reduced hours for others; office space company Convene cut 20% of staff, furloughed half of them, and closed all 28 of its US locations; and office management startup Eden let go or furloughed roughly half its workers fresh off acquiring competitor Managed by Q from WeWork for $25 million in early March.

All that comes to roughly 1,000 layoffs and 550 furloughs in the sector to date, with more cuts likely on their way.

A big question about the flex office market has always been how these companies would weather a recession or economic downturn, especially firms like WeWork whose tenants include a lot of freelancers and small- and mid-sized businesses that might cut their office budget sooner rather than later in a financial crunch.

What people were less focused on was the possibility that a global pandemic could come along, forcing a third of the world’s population into lockdown and rendering most offices rather useless. (WeWork did note in its IPO filing that the business could be adversely affected by “natural disasters, public health crises, political crises or other unexpected events for which we may not be sufficiently insured.”) But here we are, in that situation, with offices flexible and otherwise sitting empty. WeWork is offering 50% off rent to month-to-month tenants in the US, who are surely trying to get the hell out of their contracts right about now. Knotel said a third of its customers are seeking rent relief, adding that “collections have been better than expected” in April.

The existential question is whether demand for offices, and the office itself, will survive Covid-19. After months of working from home, it’s not hard to imagine many companies deciding that they don’t really need the office they once considered essential, especially in tough economic times. Offices that do re-open will likely do so at limited capacity, and with new public health precautions like keeping employees at least 6 feet apart. Knotel is updating its app so it can contact-trace by tracking its clients’ locations. Uber, when it eventually re-opens, plans to let only 20% of staff into the office on any given day. High occupancy, a measure of success for office companies, isn’t terribly compatible with social distancing. Even if flex office companies survive the current crisis, the product that they’re selling might not.

Strade aperte.

Milan has unveiled an ambitious plan to reclaim city streets for cyclists and pedestrians when it eventually re-opens after the coronavirus:

Under the nationwide lockdown, motor traffic congestion has dropped by 30-75%, and air pollution with it. City officials hope to fend off a resurgence in car use as residents return to work looking to avoid busy public transport.

The city has announced that 35km (22 miles) of streets will be transformed over the summer, with a rapid, experimental citywide expansion of cycling and walking space to protect residents as Covid-19 restrictions are lifted.

The Strade Aperte plan, announced on Tuesday, includes low-cost temporary cycle lanes, new and widened pavements, 30kph (20mph) speed limits, and pedestrian and cyclist priority streets. The locations include a low traffic neighbourhood on the site of the former Lazzaretto, a refuge for victims of plague epidemics in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Liberating roads from cars will create more space for people to traverse the densely populated city, and will hopefully encourage more people to switch their commutes to modes like biking and walking. “We think we have to reimagine Milan in the new situation,” deputy mayor Marco Granelli told The Guardian. Before Covid-19 it was unimaginable that a major city could shut down roads to traffic and repurpose them for greener modes; now the coronavirus has given urban planners that once-in-a-lifetime option.

This time last year.

Bird raises prices to trim scooter losses

Everything I learned reading Uber’s massive IPO filing

Overshearing.

My coworker Jackie cut her husband Justin’s hair over the weekend. She writes:

My husband’s hair is very thick and long, which normally is nice but in this situation was extremely stressful. I watched a YouTube video that was definitely intended for professional hair groomers and used what I think was an Italian model. My husband’s hair did not come out the way the model’s hair came out, but it was a little bit helpful, at least to have some structure. It’s totally fine for some Zoom calls, not so good for an up close, in-person job interview—as if those were happening right now. We borrowed hair scissors from the next-door neighbor that were used on their dog (I sanitized them first). They were used on Jasper the dog and Justin the human. We did it at 7pm during the Global Citizen concert, after the baby had gone to bed and we had started drinking.

Other stuff.

Treat your Instacart shopper like a goddamn human. Covid-19 relief for UK startups. Food delivery companies sued for alleged high fees amid pandemic. Uber launches “Essential” rides program in Indian cities. Former Uber employee raises $31 million for Indonesian logistics startup. Uber updates Covid-19 compensation policy for drivers, starts shipping masks to frontline workers. Bolt seeks €50 million to weather coronavirus. Blade helicopters grounded by coronavirus. Amazon-owned Whole Foods tracking unionization risk among stores. Supermarkets convert stores into fulfillment centers. Airbnb raises $1 billion in senior debt, launches online experiences, blocks most UK bookings. WeWork sues SoftBank after abandoned $3 billion share purchase. Robot-pizza startup Zume lays off 200 after funding collapses. Woe is SoftBank. The iconography of global social distancing. The best groceries to buy for lockdown.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Stay safe in these crazy times! Send tips, comments, and Overshearing submissions to @alisongriswold, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.