Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

Excited to say Oversharing made Substack’s new **newsletter leaderboard** for free publications. As the ranking is based on active readership, this is really a huge thank you to all of you for being dedicated readers. We did it! Keep it up 🙏

Scooters!

Bird launched with the same price structure across most US cities: $1 to unlock a scooter, plus 15 cents a minute to ride it. As we’ve previously discussed, the economics of that model are likely quite bad. Case in point: Bird is now raising prices.

Over the weekend, Bird lifted per-minute rates to 33 cents from 15 cents in Detroit. In Baltimore, it increased per-minute rates to 29 cents. In Austin and Los Angeles, it upped them to 25 cents per minute. Bird dropped per-minute fees to 10 cents in at least three cities. It had previously added a $2 “transportation fee” in Raleigh to offset regulatory fees charged by the city, before it bowed out of the market entirely in protest of those regulations in late March.

Bird has yet to widely share details of its new price structure, but told Detroit News it had updated its pricing range. “Similar to ride-hailing, Big Macs and cups of coffee, our pricing now varies by city,” the company said in a statement. Bird declined to provide me with a list of its new per-minute rates by city, or to explain why it couldn’t provide that information, so by all means email me any rate changes not listed above if you happen to live in a city with Bird scooters.

Anyway, here is the Bird scooter math adjusted for a per-minute rate of 33 cents, if Bird hypothetically were to charge 33 cents a minute in Louisville:

Revenue

Bird charges $1 to unlock a scooter and $0.33 per minute

At 18 minutes, the average trip would generate $6.94 in revenue, up from $3.70 at 15 cents per minute

That is a lot better! Double the per-minute rate, and you nearly double the expected average revenue per scooter. Let’s assume general operating costs remain the same, at about $2.75 per ride. That leaves net ride revenue of $4.19, or daily scooter net revenue of $14.62. Subtract the city’s daily $1 operating fee and you still have $13.62 in revenue for the day, a nearly sixfold increase on daily revenue at 15 cents per minute. Over a 29-day lifespan, that scooter averages about $395 in revenue, which is sufficient to recoup its cost and eke out a small profit at $360 and a much smaller loss on a scooter that costs the company $551 (again, see the original number crunch here).

The point I want to make is that the per-minute rate, while deceptively small, is a powerful lever Bird can pull. That’s because doubling that rate leads to a roughly proportionate increase in revenue per ride without changing the costs associated with that ride. That in turns leads to an even bigger jump in revenue per day and over the scooter’s life. I ran Bird’s estimated Louisville numbers with per-minute rates starting at 10 cents and increasing in 5 cent increments until average lifetime scooter revenue exceeded $551, the high-end cost of a vehicle. Working backward, Bird would have to charge about 42 cents per minute to break even on a $551 scooter.

Of course, that also assumes that changing the price wouldn’t change other things, like customer demand. As any ride-hail company could tell you, when prices rise, demand for the service will probably fall.

IPOs.

Are we in a bubble? Who knows! There are lots of big private technology companies that this year plan to become big public technology companies. These companies are by and large older and more mature than their predecessors of the late ’90s and early aughts, but like the dot-com era companies, they also lose gobs of money. The net profit scoreboard from S-1 filings so far this year:

Lyft lost $911 in 2018 on $2.2 billion in revenue

Jumia lost €170 million ($195 million) in 2018 on €130 million ($150 million) in revenue

Pinterest lost $63 million in 2018 on $756 million in revenue

Zoom Video Communications made $7.6 million in 2018 on $331 million in revenue

Everyone other than Zoom is losing money. I’d expect similarly of many of the other companies expected to IPO this year, although their filings are not yet public, such as Instacart, Postmates, and Uber.

These losses are on a different scale from losses we’ve seen before. Pets.com, the poster child of the dot-com bubble, lost about $150 million from when it was founded in 1999 to when it collapsed in late 2000. Webvan, another infamous dot-com company, lost $610 million from 1998 through 2000.

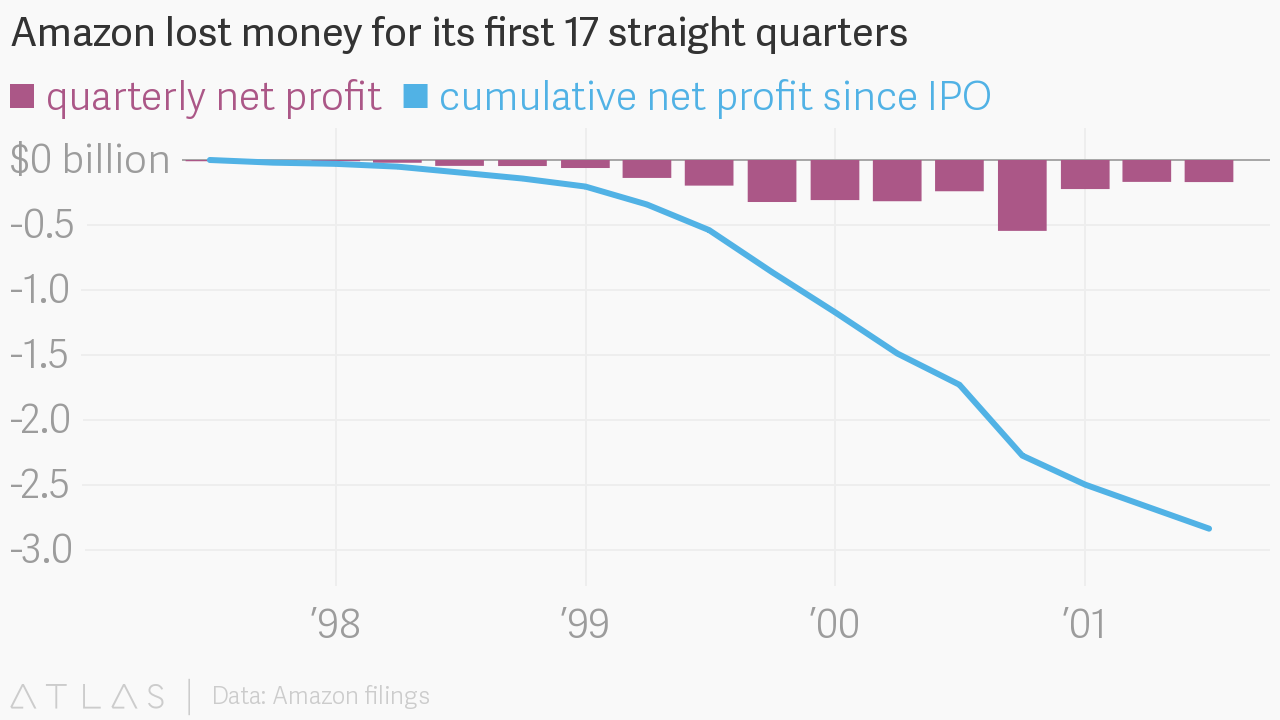

Let that sink in: The bubbliest companies of the dot-com bubble lost less over multiple years than Lyft lost in just 2018. Another fun fact: Amazon, the company that everyone loves point to as an example of how losing money eventually makes money, lost a combined $2.8 billion over its first 17 quarters as a public company, significantly less than the $4.5 billion Uber lost in 2017.

One reason modern tech startups can lose so much money is because investors are willing to provide it. Lately, the most important of all those investors is Japanese tech conglomerate Softbank and its founder Masayoshi Son.

Softbank established its $100 billion Vision Fund in October 2016. The fund has since made investments at a breakneck pace, pumping tens of billions into Uber, Slack, WeWork, Compass, Grab, Wag, Nuro, Flexport, DoorDash, and others. Softbank is reportedly seeking another $15 billion to keep the deals flowing and hey, it will probably get it. Startups used to worry about Amazon getting into their industry. Now they fear Softbank, which has approximately as much firepower as the Death Star.

Lockups.

Lyft Inc. is peeved at Morgan Stanley, The Information reports:

Lyft threatened Morgan Stanley with legal action earlier this week, demanding in a letter the investment bank stop marketing a short-selling product that the ride-hailing firm believed was disrupting trading in its stock, according to four people familiar with the situation.

The letter, sent on April 2, cited an article in the New York Post published on Monday night that said the bank was marketing a product that appeared to offer Lyft’s pre-IPO shareholders a way to get around lockup agreements that prevent them from selling for at least six months after the IPO. If true, the letter said, Morgan Stanley “is engaged in tortious interference” and the company demanded the firm stop sales of the product or face legal action.

Most Lyft pre-IPO shareholders, with the notable exception of Lyft drivers, are subject to a customary lockup in which they agreed not to sell any shares for 180 days, and specifically not to “offer, pledge, announce the intention to sell, sell, contract to sell, sell any option or contract to purchase, purchase any option or contract to sell, grant any option, right or warrant to purchase or otherwise dispose of, directly or indirectly, or” a variety of other things. You get the idea, the full language is available here under “Lock-Up and Market Standoff Agreements.” The goal of a lockup is to keep pre-IPO shareholders from dumping their stock immediately, which would depress the price of the company and be an inauspicious start to its life in the public markets.

Lyft went public on March 29 at an IPO price of $72 a share. The stock briefly jumped to $86 a share but quickly fell off that high and is currently trading around $68 a share, less than investors in the IPO paid. (Billionaire investor Carl Icahn is probably feeling pretty good about selling his 2.7% stake in Lyft to George Soros ahead of the listing.)

Here is more from The Information:

For weeks during the roadshow, Morgan Stanley salespeople had been calling early Lyft investors and pitching them on a short-selling transaction that would enable them to lock in gains, regardless of the lockup, the executive said. Morgan Stanley, which has a key role in the upcoming Uber IPO, was not involved with the Lyft IPO. JP Morgan led the Lyft deal.

One of the transactions was called a “total return swap,” a way for the investor to get the returns from short-selling the stock, while not technically selling the stock. In this instance, Morgan Stanley would be doing the short-selling, not the investor. But the investor would be able to lock in gains—the difference between what they originally paid for Lyft shares and what the sale price was struck at. In some cases Morgan Stanley offered investors the chance to share in any upside if the Lyft shares rose in value, said one person familiar with the deal. Swaps are common ways investors obscure their transactions but several investors said they had never heard of them being used to get around IPO lockups.

Whenever swaps or derivatives enter the discussion I immediately look to Money Stuff’s Matt Levine, and he did not disappoint on Lyft. I would also refer you to him for a better explanation of what a total return swap is, and how, in Lyft’s case, it “is not a way around the lockup, except in the narrow sense that Lyft can keep track of its shares but can’t necessarily keep track of who’s doing total return swaps.”

Elsewhere, Uber Technologies Inc. is expected to unveil its IPO filing tomorrow. The company plans to sell around $10 billion of stock in its offering, mostly in newly issued shares and a bit from existing shareholders cashing out. Uber will seek a valuation of between $90 billion and $100 billion, less than the much-reported $120 billion figure, reflecting the relatively poor performance of Lyft’s stock since its debut.

Community adjustments.

The We Company, formerly WeWork, is spending a truly astounding amount of money, according to FT Alphaville:

The $47bn business, which is backed by investors including Softbank's Vision Fund, previously reported a net loss of $1.9bn in 2018, after generating revenues of $1.8bn — more than double 2017's top line.

However the documents reveal new information which highlight the business's growth-at-all-costs assault on the once mundane sector of commercial real estate.

The filings specifically show WeWork’s net cash used in investing activities was $2.5bn in 2018, financed by $2.7bn of net cash provided by financing activities.

The income statement, not disclosed before, also divulges WeWork's voracious appetite for expansion. In 2018 its “growth and new market development” expense accelerated 335 per cent year-on-year to $477m. Similarly, the company's sales and marketing costs were $379m, up 164 per cent from 2017.

In perhaps the most stunning sign of how WeWork is performing, the company’s “Community-Adjusted EBITDA” margin came in at 27.5% for 2018, largely unchanged from 26.9% in 2017. The community-adjusted metric, lest you’ve forgotten, is WeWork’s preferred way of assessing its financial health. It looks at membership and service revenue and subtracts out “adjusted rent, tenancy costs, and adjusted building and community operating expenses,” which is to say, all major costs. I feel like if you’re going to go to this much trouble to engineer a financial metric then you definitely want it to be one that can show big improvement year on year. When reality closes in on even community-adjusted figures, then things really must be bleak.

This time last year.

Everyone is glad not to be Mark Zuckerberg

Other stuff.

Morgan Stanley gets stabilization role for Uber IPO. WeWork acquires Managed by Q. Driver sues Uber over unpaid signup bonus. Uber thinks driverless cars are a long way off. Seattle woman raped by man pretending to be her Uber driver. Lyft edges closer to bike-share monopoly in Chicago. Airbnb bans users headed to white supremacy conference in Tennessee. Booking.com says it’s beating Airbnb at home rentals. Airbnb donates free housing for cancer patients. Judge questions why Boston can’t regulate Airbnb. Airbnb admits it miscounted hosts with illegal listings in New York City. Amazon demotes private-label ads. Tesla cars can now change lanes on their own. China Is Forcing the World to Rethink Recycling. How men stage comebacks from Me Too allegations.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and scooter prices to @alisongriswold on Twitter, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.