Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

My good friend and fellow Substacker Walt Hickey ran the second part of our chat in last weekend’s edition of his terrific Numlock News. Sign up for Numlock, and check out our conversation on California’s controversial AB5 law.

P.S. How do you feel about color-highlighted vs. underlined links? I will probably regret saying this, but send feedback to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.

Icons.

Skyscrapers are thought to be a great sign of a bubble. The Chrysler Building. The Empire State Building. The Petronas Towers. The Salesforce Tower. “One of the indicators I have found that has worked particularly well in identifying bubbles, usually before they burst, are the world’s tallest skyscrapers,” investor and former Yale lecturer Vikram Mansharamani told NPR in 2015, suggesting skyscraper construction can indicate “overconfidence and hubris.”

Adam Neumann never built a skyscraper, but he did the next best thing: buy an iconic building. In October 2017, WeWork purchased the Lord & Taylor building on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue for $850 million, a roughly 30% premium on the property’s last appraisal.

The sale seemed like a sign of the times: A century-old, Italian Renaissance-style emblem of grandeur, high society, and historic New York City sold off to a then-7-year-old startup marketing shared offices, beer-on-tap, and retrofitted Silicon Valley culture. WeWork, fresh off a SoftBank-led funding round that valued it at $21 billion, planned to convert the building into a mix of leased office space and its own corporate headquarters.

Two years earlier, flush with capital after a $1 billion venture round valued it at $51 billion, Uber had also bought a landmark property. In September 2015, Uber, then 6-years-old and led by co-founder Travis Kalanick, paid $124 million for the derelict Sears building in Oakland, California, a massive 1920s-era department store that was severely damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Uber planned to restore the building, complete with an airy central atrium, and re-open it as a second Bay Area headquarters housing around 3,000 employees by 2017.

Tech companies are no strangers to impressive campuses: the Googleplex, Apple Park, the Amazon Spheres. But Uber and WeWork sought something else: history remade in their image.

“To design its new headquarters in 1914, Lord and Taylor hired architecture firm Starett and Van Vleck, which provided amenities for employees like dining rooms and a gymnasium—much like how WeWork is now bringing expansive common areas and wellness programs to the modern workplace,” WeWork wrote in an October 2018 blog post.

These companies were young, but they were also on the top of the world, anointed startup royalty by awestruck private investors. How better to cement their legacies than by leaving their mark on icons of the past?

For both Uber and WeWork, these iconic buildings proved to be their skyscrapers. In August 2017, nearly two years after it bought the Sears building and two months after Kalanick resigned as CEO, Uber said it was exploring a sale of the property, which the 3,000 employees had never moved into. That December, Uber sold it to urban real estate investor CIM Group for $180 million. That was barely more than what Uber paid for the property plus the $40 million it had said it planned to spend on building rehabilitation, though it’s unclear how much Uber ultimately poured into the project. In December 2018, payments company Square signed an office lease on the property.

WeWork bought the Lord & Taylor building through a joint venture of its own real estate fund and private equity firm Rhône Group. A year after the sale was first announced, WeWork was still seeking equity investors to fund it. The deal eventually closed in February 2019 after WeWork secured a loan from investors including JPMorgan. WeWork later disclosed that the “424 Fifth Venture” was financed by $50 million from WeWork, $112.5 million from its real estate fund, $125 million in equity from other investors, and a debt facility of up to $900 million. The 20-year lease agreement included total future minimum rental payments of $1.7 billion.

You know what happened next: the failed IPO, the ousting of Adam Neumann, a SoftBank-funded bailout, and cost cuts and layoffs. History crumbles much more quickly than it is made. The Lord & Taylor building suddenly looked less a triumph than a lingering reminder of Neumann’s excess, and yet another burden for WeWork to unload. The company is now reportedly in the process of doing just that. Per The Real Deal, WeWork is in talks to sell the Lord & Taylor building to Amazon for close to $1 billion, completing the symbolic handoff from brick-and-mortar to digital. That price would be slightly less than the total WeWork is thought to have spent on the building including renovations. These days, WeWork might count even a small loss as a good investment return.

Great expectations.

It is pretty much always the worst of times in New York City’s ride-hail market. The latest driver grievance is Uber’s and Lyft’s response to the minimum pay rules the city implemented in February 2019.

Both Uber and Lyft stopped accepting new driver signups last year in response to the rules. But the companies also went a step further and limited access to their apps, in an effort to prevent having more drivers on the road than demand from customers can accommodate. The rules New York City passed penalize companies that flood the streets with drivers but fail to provide them with actual work, wasting drivers’ time and clogging up roads. Lyft told drivers they would receive “priority” to drive by maintaining a high acceptance rate and completing a minimum number of trips per week. Uber has devised a similar system, and introduced an hourly shift-like scheduler.

Earlier this month, the Independent Drivers Guild, a non-union driver advocacy group in New York, got involved. “In response to city utilization rules, Uber and Lyft are locking thousands of drivers out of the apps for minutes, hours, and days at a time to avoid paying them a fair wage,” the IDG wrote in a statement. “The Independent Drivers Guild warned the Taxi and Limousine Commission about the app company violations for months, but the Commission failed to take action.”

A classic economic debate is whether raising wages via something like a minimum wage leads to job loss. The US Congressional Budget Office, for instance, projected last year that a $15 federal minimum wage would lift 1.3 million Americans out of poverty, but also put roughly the same number of people out of work. Other research says not to worry so much.

I mention this because a version of that debate is playing out right now in New York City’s ride-hail market. Uber and Lyft worked in the sense that anyone could sign on at any time and potentially earn money because the companies were under no obligation to compensate them for all the time those workers were signed onto the app, only for the time they were on a job. In other words, if a driver chose to spend a long time waiting for fares to come in, or to work for perhaps subpar wages, that was their problem and not the companies’. Now, forced by city regulators to pay drivers a wage equivalent to $15 an hour and adjusted for utilization, Uber and Lyft have constrained their workforces. For some drivers to earn more, others have found themselves out of work.

This outcome was indirectly anticipated in a working paper that economist John Horton and Uber researchers first released in 2017. The paper argued that so long as Uber operated in an open market—meaning drivers could sign on to work whenever they liked—then for Uber to raise prices had no substantial long-term effect on drivers’ hourly earnings. That was because higher fares induced drivers to work more hours, and also riders to take Uber less: an increase in labor supply and decline in demand. Drivers might make more on any given ride, but with less work to go around, their average hourly earnings ultimately reverted to where they were before the fare hike.

Here is what I said in July 2018:

The great irony of this paper was that if you inverted the framing, it was the best possible argument for capping the number of Uber drivers on the road. The core assumption of the paper—the reason why Uber argued it couldn’t pay drivers more—was that the ride-sharing market “is highly elastic,” with existing drivers facing “no quantity restrictions on how many hours to supply” and new drivers facing “minimal barriers to entry” (that is from the abstract of Uber’s paper).

How do you change that? You make the market less elastic. You start to limit supply, and suddenly wages can rise.

New York City didn’t create a strict cap (at least, not at first, and then it did, and that failed), but it devised a dynamic one by tying the minimum hourly wage to driver utilization. That meant Uber, Lyft, and other ride-hail companies couldn’t afford to have drivers signing on any time they liked, because if the demand wasn’t there and those drivers were underutilized, the companies would have to pay more to make up the difference. So Uber and Lyft did the logical business thing, and limited app access. Of course drivers are upset. Economic realities have crashed head on into the gig economy dream that anyone willing to hustle could earn a good—even great—living through app-based work, and those dreams die hard.

Oy-o.

Layoffs at Indian budget hotel chain Oyo continue, with the startup reportedly cutting dozens of UK staff:

Oyo previously disclosed it was running a 30-day consultation with UK staff, but didn’t say how many jobs were at risk. The process concluded last Friday and sources suggested 50 to 100 staff have been cut, which is 10-20% of the company’s UK workforce.

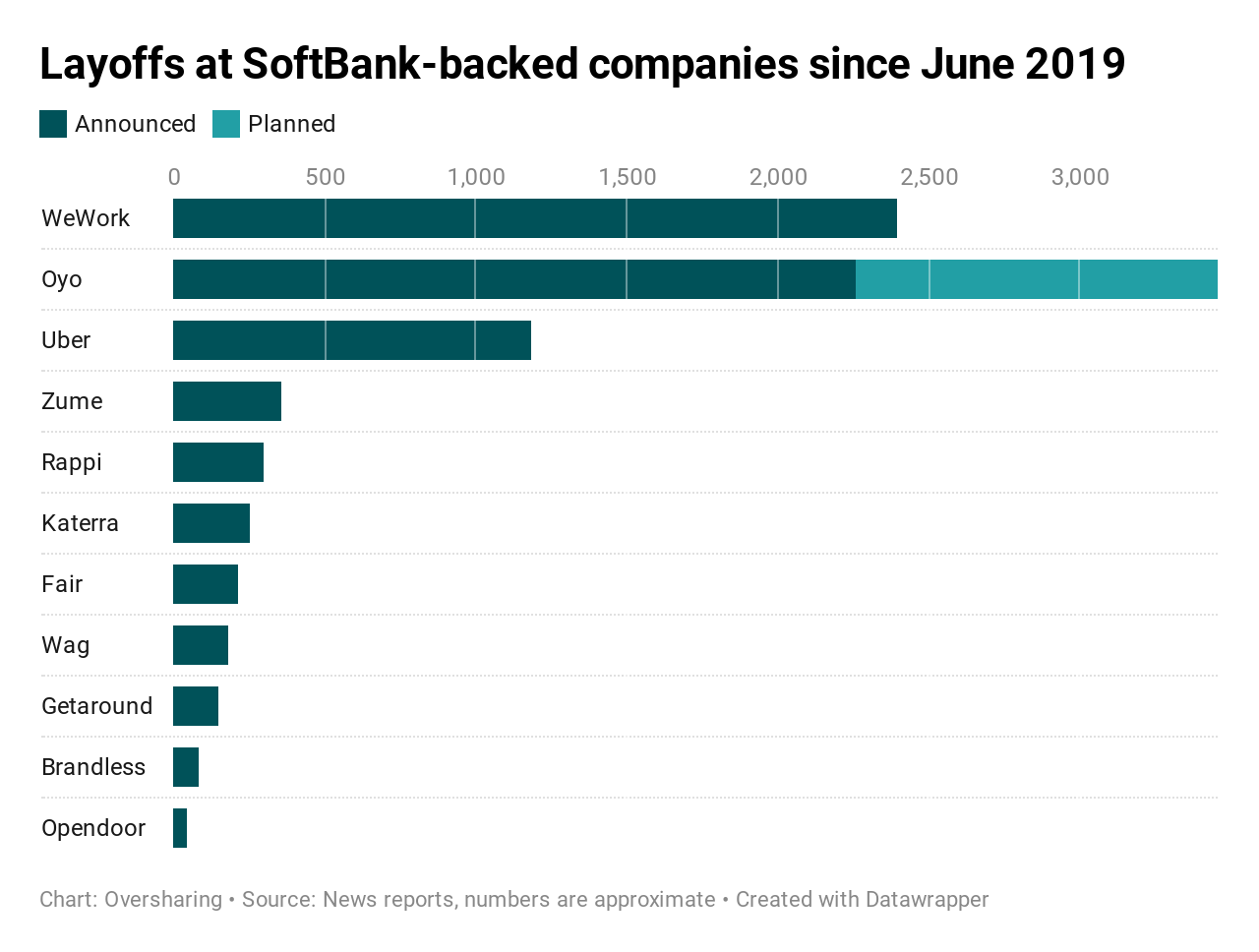

At the high end of that range, that brings layoffs at SoftBank-backed companies since last June to nearly 7,500.

Garbage language.

I love this, from Molly Young in Vulture, on the epidemic of corporate speak:

In 2011, I was dropping printouts on a co-worker’s desk when I spotted something colorful near his laptop. It was a small foil packet with a fetching plaid design.

My co-worker’s assistant was sitting nearby. “Caroline,” I said, “do you know what this is?”

“Yeah,” she said. “Jim belongs to some kind of runners’ club that sends him a box of competitive running gear every month.”

The front of the plaid packet said UPTAPPED: ALL NATURAL ENERGY. The marketing copy said, “For too long athletic nutrition has been sweetened with cheap synthetic sugars. The simplicity of endurance sports deserves a simple ingredient — 100% pure, unadulterated, organic Vermont maple syrup, the all-natural, low glycemic-index sports fuel.”

It was a packet of maple syrup. Nothing more. Whenever I hear a word like operationalize or touchpoint, I think of that packet — of some anonymous individual, probably with a Stanford degree and a net worth many multiples of my own, funneling maple syrup into tubelets and calling it low-glycemic-index sports fuel. It’s not a crime to try to convince people that their favorite pancake accessory is a viable biohack, but the words have a scammy flavor. And that’s the closest I can come to a definition of garbage language that accounts for its eternal mutability: words with a scammy flavor. As with any scam, the effectiveness lies in the delivery. Thousands of companies have tricked us into believing that a mattress or lip-gloss order is an ideological position.

This “garbage language” I think is key to how so many not-tech companies become, in the popular mindset, tech companies. Like I said last week, we have grown all too willing to apply the “tech” label to digital natives that wrap themselves in the trappings of tech-startupdom: venture capital funding, slick apps, podcast ads and discount codes, and of course corporate jargon. Startups are always disrupting, innovating, growth hacking, optimizing, hustlin’. If you look like a startup and talk like a startup, you too can be a startup. Read the whole thing! Then circle back, so we can sync up to leverage some takeaways.

Other stuff.

Grab and Gojek discussing merger. Yes, ride-hailing increases emissions. Uber returns to Colombia after three-week suspension. Ontario labor board rules Foodora couriers eligible to join a union. Shipt shoppers organize. Travis Kalanick’s CloudKitchens loses UK head. Uber Eats head Jason Droege steps down. Lyft resumes e-bike rentals in New York City. HopSkipDrive raises $22 million for school transport. NHTSA suspends driverless EasyMile shuttles after passenger injury. UK-based HungryPanda raises $20 million for online food delivery. Tier Mobility extends series D funding to over $100 million. Fast-food by drone. Uber tests taxi-like ads on top of cars, Lyft buys rooftop ad startup. New York City accused of fraud over taxi medallion crisis. Delivery provider Skipcart cuts ties with Walmart. New Uber competitor launches in New York. Lime scooters return to Redmond. Montreal bans Bird and Lime. Estonia drafts e-scooter rules. Lime slashes pay for juicers. Spin deploys public scooter charging hubs in Phoenix. Coronovirus trips up China’s home-rental startups. Susan Fowler’s memoir is out soon. Waymo hiring spree. WeWork postmortem. DoorDash gets Krispy Kreme. Big Dog Becomes Mayor of Small Colorado Town. “When was the last time an average New Yorker on the street knew the name of the head of a transit agency?” Lambda School’s Misleading Promises. Deliver Us, Lord, From the Startup Life.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and link-styling opinions to @alisongriswold, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.