Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

I am back from a 10-day road trip around the desert in the US southwest, which I highly recommend. Here’s a photo of Bryce Canyon, an incredible place with rock layers so uniform that even Mary Berry would approve of them.

Scooters!

Scooters!

The regulators have had their revenge in San Francisco:

The city has selected two San Francisco startups, Scoot Networks and Skip, to offer dockless rentals of 1,250 electrified stand-up scooters (625 each), starting by Oct. 15, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency said on Thursday.

A dozen companies had competed for up to five permits in the yearlong scooter pilot program San Francisco’s MTA devised in June. In the end, the MTA awarded only two, to the companies that were explicitly uninterested in moving fast or breaking things. The message to Bird, Lime, Lyft, and Uber: check yourselves.

San Francisco had hinted this crackdown was coming. “I myself am concerned that companies here have asked for forgiveness instead of permission,” Malcolm Heinicke, vice chairman of the board for the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA), said at a meeting on May 1. “And while I’m willing, personally, to give some forgiveness, I’m also not necessarily willing to reward past behavior.”

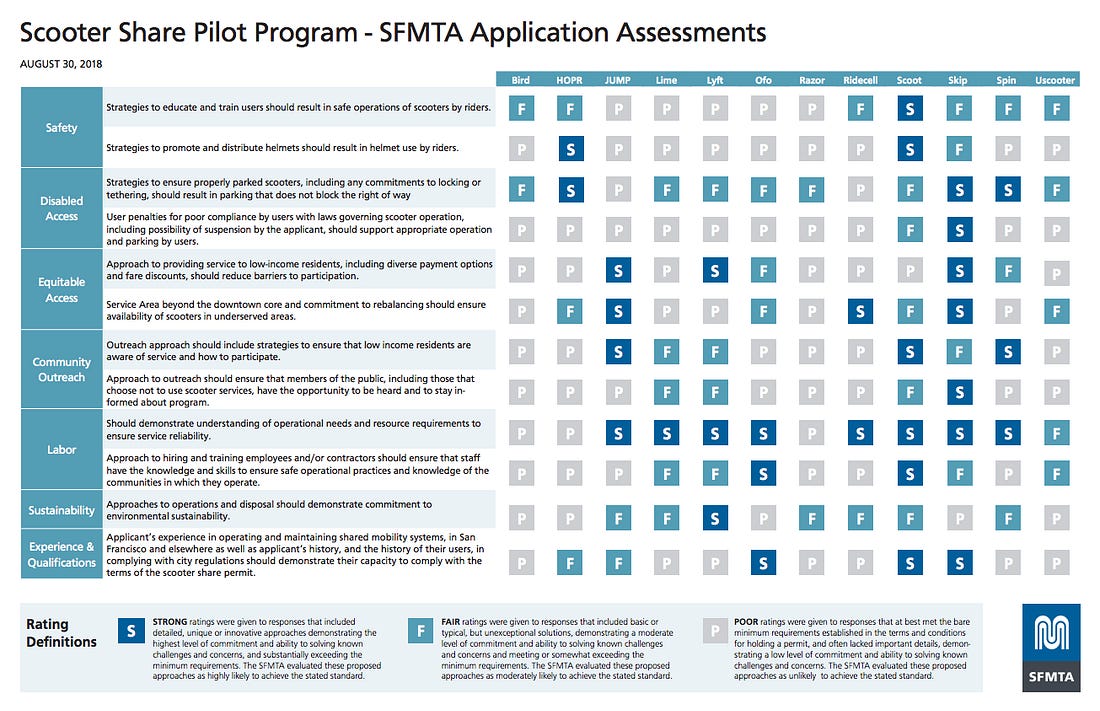

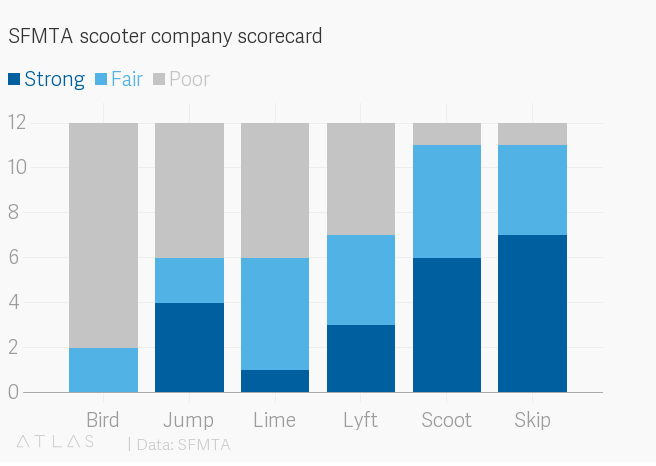

That brings us to The Scorecard (pdf).

Lime called the SFMTA decision “disappointing” and said the city had selected “inexperienced scooter operators that plan to learn on the job, at the expense of the public good.” Scoot, on the other hand, was celebrating. “It’s a good day in scooterland,” CEO Michael Keating said.

Bird, at any rate, doesn’t seem to have given up the asking-later style of doing business. Dockless electric scooters remain illegal in New York City, and yet they’ve been spotted repeatedly in the five boroughs, including over the weekend by Verge reporter Andrew Hawkins in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bed-Stuy.

Strange partners.

Toyota is putting $500 million behind Uber and joining it on its journey toward self-driving cars. The goal is to create driverless Toyota Sienna minivans, which, you know, will take over driving the kids to soccer practice. Here is the baffling part:

As for putting those cars into the streets and filling them with passengers, well, someone else will do that. Toyota and Uber are on the hunt for a third partner, job description to come.

I know I was in the desert for a while, but what? If Uber isn’t interested in putting passengers in self-driving cars, why is it even bothering? Uber’s whole thing, its shtick, the reason it is supposedly worth $60 billion, plus or minus a couple billion, is that Uber is good at putting people in cars. Uber didn’t topple the taxi industry and become a household name by being like, you know what, we’re going to assemble a fleet of cars and drivers and then let someone else do the rest. Uber also didn’t get into self-driving cars because it dreamt of being the next GM; it got into self-driving cars because it thought that when the world eventually shifted toward driverless technologies, it could put people in driverless cars better than the competition.

Ok, so, that third partner:

Uber’s job description for that third party fleet operator remains vague. “We haven’t actually taken the time to do a wholesale evaluation of what’s out there,” says Jeff Miller, Uber’s head of strategic initiatives. He says the company is instead building up its fleet management capabilities today, with its self-driving Volvos.

The subtext to all of this is that Uber’s driverless car operations are in turmoil. The company is reportedly divided on the fate of the Advanced Technologies Group, with one faction pushing for a partnership or sale of the unit, and another urging Uber to maintain its investment. Uber suspended all of its driverless car tests in March after one of its vehicle struck and killed a pedestrian in Tempe, Arizona. The company later shut down its autonomous operations in Arizona and laid off about 100 driverless car “operators” in Pittsburgh and San Francisco.

On top of that, Uber’s losses on self-driving tech have been significant, at $125 million to $200 million a quarter, or 15% to 30% of its total quarterly loss. Uber’s Dara Khosrowshahi reportedly considered shuttering the autonomous vehicle unit entirely when he took the job, though he’s since warmed to it. Khosrowshahi is working to trim losses ahead of a potential public offering in 2019.

Another awkward element to this is that SoftBank in late May invested $2.25 billion into Cruise, GM’s autonomous vehicle unit. GM, you might also recall, has put $500 million behind a self-driving car partnership with Lyft. SoftBank is fond of hedging its multibillion-dollar bets on transportation and it made this investment less than six months after taking a 17.5% stake in Uber that made it the company’s largest investor. There are no friends in ride-hailing, only enemies and very rich frenemies.

C.O.O.K.

California last week passed America’s strongest net neutrality rules, in a stark rebuke to the federal government. It also passed the homemade food bill, also known as the “tamale bill,” which allows cities and counties to issue permits to regular people to prepare and sell food at home.

The bill is the product of some hard work by now-defunct startup Josephine, which launched in 2014 with the aim of helping local residents start their own catering businesses, a sort of Uber for home-cooked food. The company had raised $3 million in seed funding (remember when not everyone got $1 billion?) but closed up shop earlier this year. Josephine’s unsavory demise was due largely to its inability to contend with health regulations, which stipulated that making and selling food from one’s home, rather than a commercial kitchen, was illegal and punishable by a fine.

The bill defines a “microenterprise home kitchen” as a “food facility that is operated by a resident in a private home where food is stored, handled, and prepared for, and may be served to, consumers,” with no more than one full-time employee and no more than $50,000 in gross annual sales. Home kitchens would be exempt from many of the codes governing “food facilities,” but would require the home kitchen to be reported to the state department of public health if it received three or more unrelated food safety or hygiene complaints in a calendar year.

“The underground food economy already exists—from firehouse pancake breakfasts to Asian grandmothers selling dumplings on WeChat to the neighborhood tamale lady,” says my colleague Simo Stolzoff, who in a previous life headed up comms for Josephine. “Better to create a permitting system to regulate it above ground than to try and criminalize it all.”

Measurements.

“How big is the gig economy?” asks the US Census Bureau. “The answer depends on how you define ‘gig economy.’” The post is a preface to a recently revised working paper, “Measuring the Gig Economy: Current Knowledge and Open Issues,” from four economists. They suggest gig economy measurements could be improved by “more probing questions” in household survey questionnaires” and “integrated data sets” that combine data from multiple sources.

The paper is somewhat long and technical, and reiterates a lot of things that close watchers of the gig economy (or frequent readers of this newsletter!) already know. That said, it’s good to know people are still thinking about this, and that, as the paper’s authors conclude, “the widely perceived rise of the gig economy is as yet not well measured or well understood.”

That much was clear in June, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its first contingent worker supplement since 2005, and found that share of people working in “alternative” arrangements had actually declined over the intermittent period. The BLS added four new questions to its most recent contingent worker supplement, designed to identify people who “found short tasks or jobs through a mobile app or website and were paid through the same app or website,” aka worked in the gig economy. The BLS said in June that it was still evaluating the data from those questions, and would release a separate report on its findings by Sept. 30.

This time last year.

Uber employees “embarrassed” by their board, Handy fights the NLRB, layoffs at Postmates

(Like this throwback to Oversharing’s archives? Hate it? Have another strong opinion not supplied here? Let me know by replying to this email, or sending a note to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.)

Other stuff.

Lyft wants to IPO before Uber. Apple self-driving car rear-ended in first crash. Uber shortlists international destinations for flying taxis. Uber interested in using drones for Eats. Judge tosses Uber investor lawsuit. Uber is building its own scooter. Dara reflects on his first year at Uber. Careem hits 1 million drivers. Grab Ventures launches in Indonesia. Kroger expands Instacart to half US stores. Chariot approved to use transit-only lanes in San Francisco. Trader Joe’s files restraining order against Airbnb. Shine raises $9.3 million to build a bank for freelancers. Moody’s pulls WeWork credit ratings. The Cult of WeWork. Every Generation Gets the Beach Villain It Deserves. “I would say Uber has built a better mousetrap.”

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and sightings of Bird scooters in Brooklyn to @alisongriswold on Twitter, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.