Time to grow up.

“A week ago, I did not think I was going to get the job, so this is pretty cool,” Dara Khosrowshahi said at Uber last week, in his first all-hands meeting since being named the company’s next CEO. “Based on everything I read!” he added, to a lot of laughs.

Uber’s board may be the leakiest thing around after the White House. There were leaks aplenty in the search leading up to Khosrowshahi’s selection. The day he was picked, the board released a statement promising to inform employees of their decision first. Minutes later, it leaked to the press. “Everyone was following along on Twitter during the board meeting because they knew something was going to leak,” a longtime Uber employee told me last week. “It’s just not how a company should work, and it’s really disappointing.”

The board has had its fair share of missteps. David Bonderman, a partner at private equity firm TPG, resigned from the board in mid June after snubbing women at an all-hands meeting on sexism. Venture-capital firm Benchmark reportedly helped oust Kalanick, then sued him in a struggle over board seats. Garrett Camp, Uber’s lesser known co-founder and also a board member, has rankled staff by sending company-wide emails and positioning himself as a “Travis surrogate” after being relatively absent for the last eight years. At the Aug. 30 all-hands, board member Arianna Huffington nearly let slip that Expedia CFO Mark Okerstrom would be Expedia’s next CEO, hours before the company actually announced it.

Now that Travis Kalanick is out and Khosrowshahi is in, the greatest lingering concern about Uber’s management is not a single person but the eight who sit on its board of directors. “Everyone’s really embarrassed by the board right now,” the longtime employee told me. Another called for the board to “grow up.” A board doesn’t run a company but it typically ratifies all major strategic decisions, such as financing, mergers and acquisitions, and changes to senior leadership. In theory, a board also provides a check on the people at a company with a lot of power.

Of course, by extension, the board can also choose not to do these things, or to look the other way if powerful people are doing questionable things that produce good results. That is pretty clearly what happened for years with Uber, as the board allowed Kalanick and his team to deliberately flout the law in their efforts to open up new markets to the ride-hailing model. No one seemed to care until this year, when a series of scandals eroded Uber’s political capital, and the government opened a federal probe into one of the company’s more egregious efforts to evade law enforcement. By the time the board started trying to right Uber’s ship, a lot of it was already sunk.

God view.

Elsewhere in Uber, the company has decided to stop tracking riders after their rides end:

Uber Technologies Inc is pulling a heavily criticized feature from its app that allowed it to track riders for up to five minutes after a trip, its security chief told Reuters, as the ride-services company tries to fix its poor reputation for customer privacy.

The feature eliminated the “while using the app” option for location tracking in iOS, forcing iPhone users to choose between letting Uber “never” and “always” track their location. The former was an annoying user experience that required manually entering your dropoff and pickup location for every ride; the latter could make you feel uneasy about your privacy. Uber said it was only gathering data on the five minutes after a trip ended, but this is also the company that created “greyball” and “god view.”

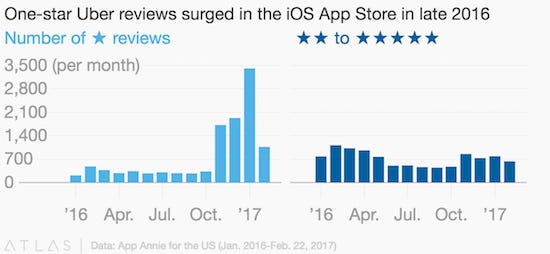

Uber made its changes to the iOS location tracking settings last November when it redesigned the rider app. The feedback was immediately negative. One-star ratings for Uber soared in the iOS App Store, with reviewers deeming it “sketchy,” “ridiculous,” and “terrible.”

Uber’s current App Store rating is less than two stars. Fortunately for Uber, a low rating in the App Store doesn’t get you deactivated.

Handy complaints.

The National Labor Relations Board last week issued a complaint against Handy, a cleaning and handyman services company that hires its workers as independent contractors. As you might expect, the complaint alleges that Handy’s workers are not contractors but rather “statutory employees” entitled to federal labor law protections, like a guaranteed minimum wage. As you also might expect, Handy vehemently disagrees with the NLRB’s interpretation. “We hope this complaint draws attention to the need for better legislation, rather than litigation that hurts professionals and their customers across Handy and other on-demand services,” Brian Miller, Handy’s general counsel, said in a statement to Bloomberg.

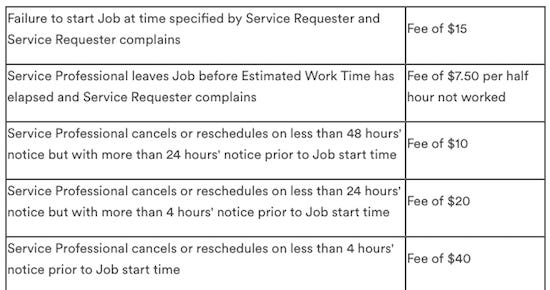

An incredible thing about the “sharing” economy is how companies that push policies that are probably not great for workers still manage to spin those policies as very good for workers. Uber is one thing, and there is a genuine debate to be had over the value of flexibility to workers, but Handy has pushed the limits of what a contractor can be much more aggressively. In 2015, when I reported on them for Slate, Handy required its cleaners to attend training sessions and follow a Handy checklist on jobs. It also docked their future pay if they showed up late to a job, canceled on short notice, or missed an appointment entirely. Handy still uses most of these fees, outlined in “schedule 3” of its terms for “pros,” for example:

Handy has tried to shoehorn its employment preferences into law. Last year, it began pushing for a bill in its home state of New York that would make it easier for companies to contribute to hypothetical portable benefits funds for workers in exchange for codifying those workers as independent contractors. Tl;dr, you get some benefits for the price of all other standard labor protections. As I’ve said before, one thing the sharing economy loves to share is liability; a second is employer responsibility.

Meanwhile, Grubhub is headed to trial in California over whether two of its former drivers were employees rather than contractors. And a federal judge in California gave preliminary approval to an $8.75 million settlement between Postmates and couriers who claim they were misclassified as contractors and paid less than minimum wage.

“Centralizing functions.”

Postmates has laid off all of its city managers, some 15 people across cities including Boston, Nashville, St. Louis, and Las Vegas. “Centralizing these functions will enable us to execute more quickly—and ultimately help us be more nimble and effective as we continue to aggressively scale the company,” an unnamed company spokesman told TechCrunch in a statement.

Postmates has been struggling to become profitable for the better part of two years. CEO Bastian Lehmann first promised investors in May 2015 that the company would be profitable by 2016; when it didn’t happen he pushed the target date to 2017, and then 2018. In a 2016 pitch deck to investors, which I obtained last year, Postmates revealed that it lost $47 million before interest and tax in 2015 and expected those losses to grow to nearly $60 million in 2016, before shrinking dramatically in 2017.

It was never clear in that pitch deck what Postmates planned to do to pull off that turnaround, but this year the company has made several decisions that seem designed to cut costs and bolster margins, of which cutting city managers is the latest. In March, Postmates laid off its 30-ish community managers, citing “consolidated… support functions.” Postmates has also spent the last several months tweaking its “service fee” on orders, first increasing it to 9.99% from 9%, and then briefly to 12.99%, before settling on a “variable percentage based fee,” the startup equivalent of a ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Other stuff.

Kansas Teenager Leads Trooper on Chase, Then Tries Uber. Orphaned Baby Squirrel Takes Uber to Boulder County Wildlife Center. House vote planned on self-driving cars. Samsung gets California permit to test self-driving cars. Airbnb Joins Race for AI Talent. Airbnb partners with Zola for wedding gifts. Cambridge Airbnb host reports $20,000 in damage. Bushwick Airbnb host crams 34 guests into nine rooms. Uber repays Massachusetts drivers for toll fees. Uber ties up with shopping malls. Lyft extends service. Philippines lifts ban on Uber. Didi-backed Taxify undercuts Uber in London. Toyota invests in Grab. German aviation startup raises $90 million. Firefox founder heads to Uber. Uber employees on Blind are pro Dara Khosrowshahi. Uber’s secret HR war. Gig economy lessons from Hollywood unions. Ride-hailing aggregator. Airbnb for boats. Home offices. Caravan rentals. VIP hustlers. RIP Juicero.