What went wrong with Jokr

With a close look at Jokr's unit economics, as told by its CEO

‘Instant’ delivery startup Jokr is bowing out of the U.S. to focus on operations in Latin America. The company told customers in an email this week that its last day of deliveries in its two U.S. cities—New York City and Boston—would be Sunday June 19. Per Bloomberg, Jokr operated nine micro-fulfillment centers or ‘dark stores’ in New York and Boston, a fragment of the roughly 200 it runs worldwide. Jokr will also cut around 50 people from its 950-person office staff. “While we were able to build an amazing customer base (thank you!!) and lay the groundwork for a sustainable business in the US, the company has made the tough decision to exit the market during this period of global economic uncertainty,” Jokr said in its email.

Jokr’s U.S. exit comes just two months after it quietly left Europe, after failing to find a buyer for its operations there. The Information also reported in January that Jokr was looking to sell its New York business, where it faced heavy losses. Jokr is the latest entry in the instant delivery crash, which has seen at least four other players cut staff, slash spending, and exit markets in an effort to stem losses and refocus on profitability.

What went wrong for Jokr, and could it actually have a future in Latin America? In this subscriber-only edition of Oversharing, we go deep on Jokr’s origins and the instant delivery pitch; break down its unit economics in the U.S. vs. LatAm; and contextualize Jokr in the broader instant delivery landscape. Deep industry dives like this are available exclusively for paid subscribers. Lots of Oversharing readers at your company? Sign up at this link to purchase a group subscription for 20% off. More info on how group subscriptions work is available from Substack here.

The backstory

Jokr was started in 2021 by Ralf Wenzel, a German entrepreneur who previously founded Foodpanda, an online food ordering startup that sold to German competitor Delivery Hero in December 2016 for an undisclosed price. After the sale, Wenzel served nearly three years as chief strategy officer at Delivery Hero, then became a managing partner at Softbank. During that time he also spent 7 months as chief product and experience officer at WeWork and 6 months as executive chairman at budget hotelier Oyo.

Wenzel left Softbank in March 2021 and launched Jokr the following month with $20 million in funding from German venture firm HV Capital, Softbank, and Tiger Global. Jokr’s first markets were Mexico City, Lima, and Sao Paolo, and Wenzel promised that New York, Bogota, and European cities would follow. “We are building an Amazon on steroids,” he told Reuters in an April 2021 interview. “It’s not just convenience on demand but a new generation of retail.”

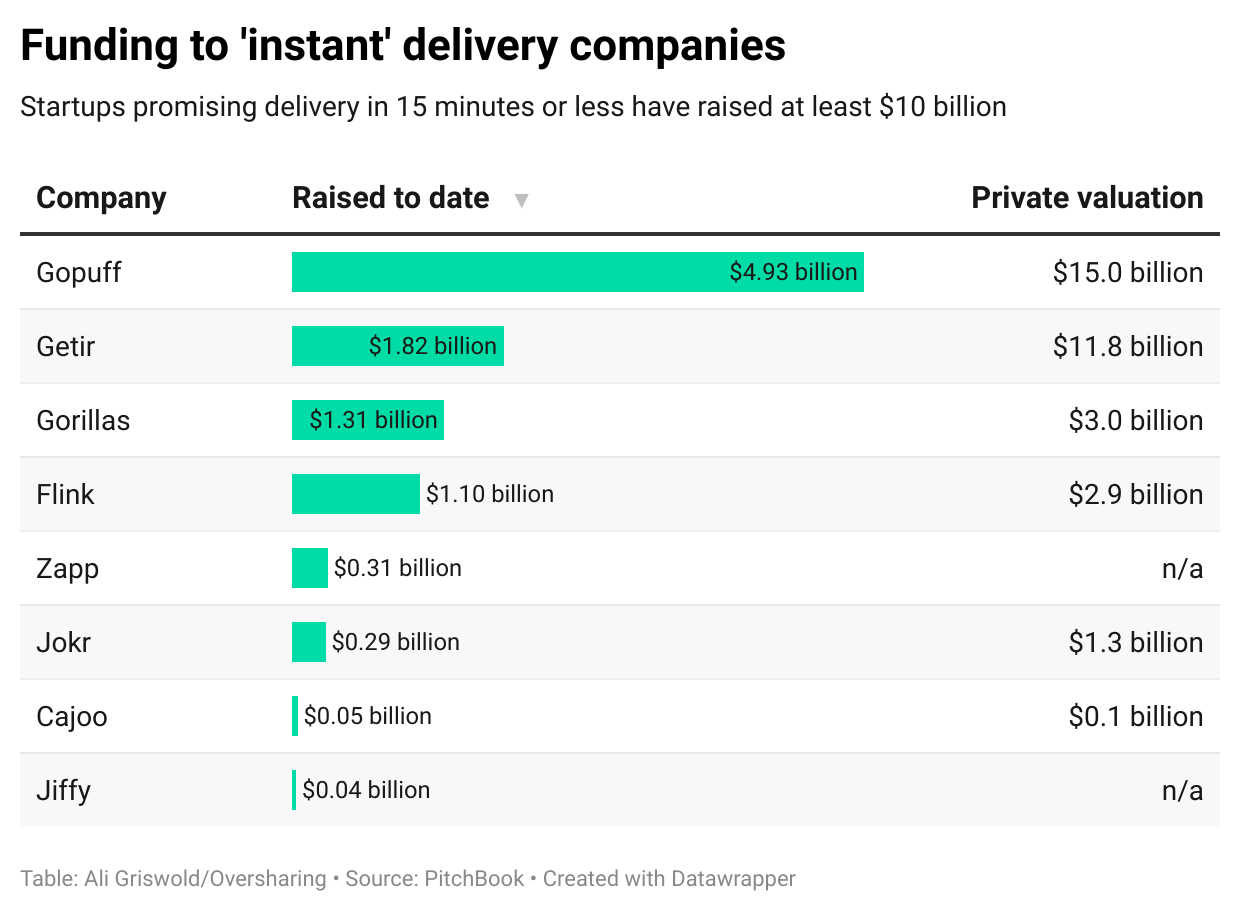

Wenzel launched Jokr at a good time. Investors were pouring money into a new crop of startups that, like Jokr, promised to deliver groceries and other goods in 15 minutes or less using urban networks of micro-fulfillment centers or ‘dark stores.’ By December 2021, less than a year after launch, Jokr had amassed $288 million in venture funding at a valuation of $1.3 billion. Other rapid delivery startups boasted even greater funding tallies. GoPuff did two billion-dollar rounds in 2021 (Softbank participated in both) and raised another $1.5 billion this May for a total war chest of $4.9 billion. Gorillas, a German rapid delivery startup founded in May 2020, had raised $1.3 billion by the end of 2021 at a $3 billion valuation.

The pitch

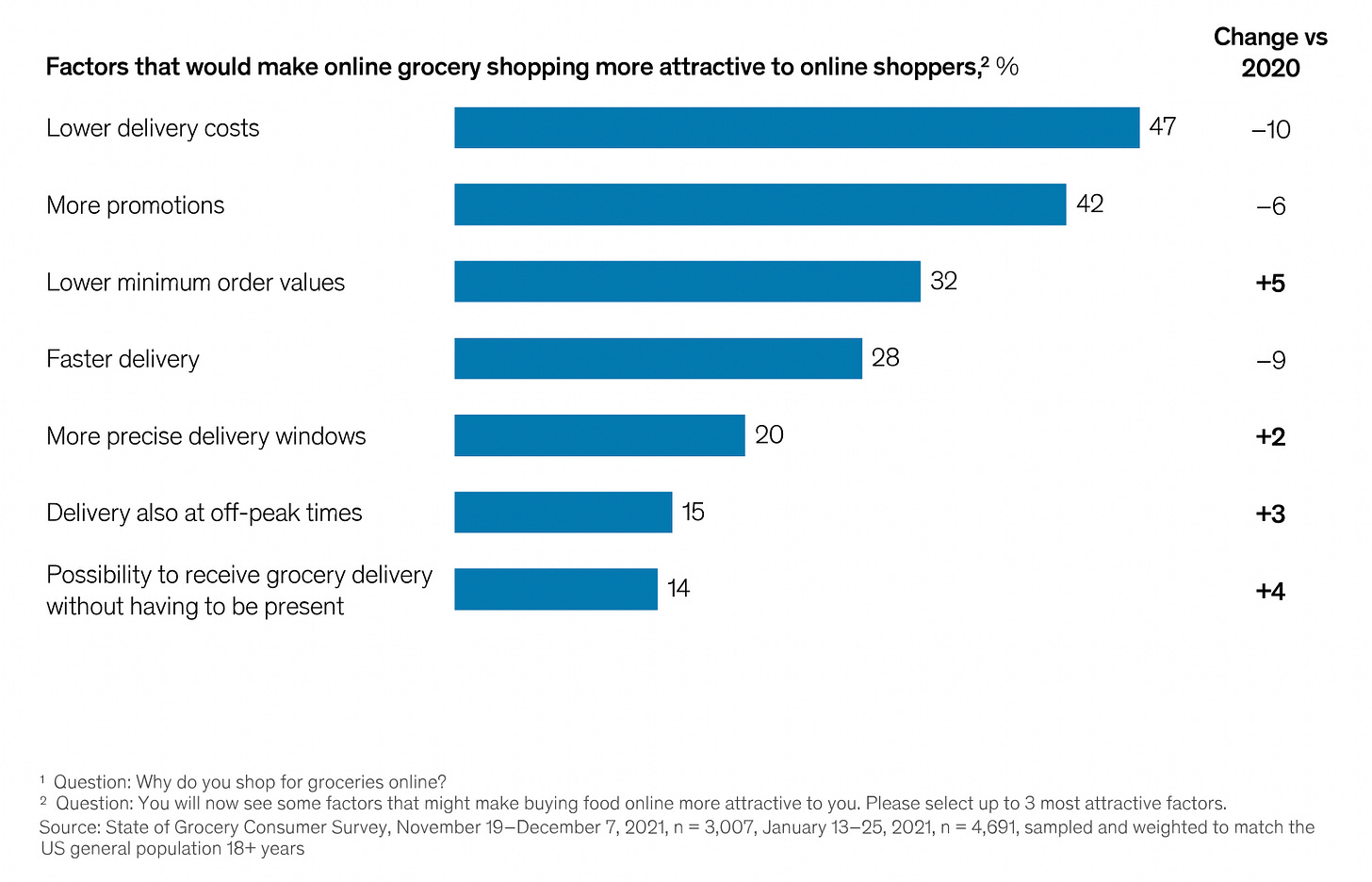

Wenzel has consistently said that Jokr isn’t just about convenience; it’s about creating a new kind of commerce that supports urban consumption habits. The rapid delivery bet is that time- and space-constrained urban consumers are increasingly shopping for groceries more frequently and as needed, rather than in large weekly baskets. A January 2021 YouGov survey found that grocery shopping “when required” is the second-most popular way of shopping in the U.S. and the U.K., behind a weekly grocery shopping routine. The pandemic also provided a turboboost to online grocery, with the North American market experiencing the equivalent of five years of growth in five months. Top reasons consumers have switched to online grocery include convenience, flexibility, and speed. While delivery costs remain a key hurdle, a 2021 McKinsey survey found that consumers are less concerned about costs and promotions than they used to be, and increasingly interested in being able to order smaller basket sizes, book precise delivery windows, and get groceries delivered at off-peak hours or without needing to be home.

To make deliveries in 15 minutes or less possible, these companies rely on a network of micro-distribution centers scattered throughout each city, often called ‘dark stores.’ These stores look similar to a corner shop or bodega but aren’t open to the public. Instead, they’re manned by workers, often called ‘pickers,’ whose job it is to quickly assemble orders as they come in. One picker in a Getir dark store in London told tech reporting site Sifted last fall that he typically assembles orders in just 7 to 45 seconds.

Instant delivery startups own or lease their distribution hubs and manage their inventory and supply chains. They also tend to hire their delivery and dark store workers as actual employees with benefits. This marks a big shift from the ‘asset-less’ model that was popularized by companies like Uber, Airbnb, and Instacart during the gig boom of the 2010s, in which startups pitched investors on their roles as middleman technology platforms that would connect two sides of a market but not be weighed down by stores, inventory, or employed workforces. If you order groceries from Uber Eats, for instance, a self-employed courier goes to a regular shop to pick up the items you ordered and then delivers them to you; if you order the same items from a Gorillas or Jokr, they’re plucked from the micro-fulfillment center by an employed picker and delivered to you by an employed courier.

The delivery pendulum, in other words, is always swinging. The asset-less ‘Uber-for-X’ model came about in response to the dot-com crash and the disastrous collapse of startups like Kozmo.com and Webvan, which attempted to make same-day delivery happen by selling products from their own warehouses. When the Ubers and Airbnbs of the world came around, they reassured anxious investors that they wouldn’t own any big assets like Kozmo or Webvan. The new crop of delivery startups has had time to study the middleman delivery model and thinks they can do it faster, better, and cheaper by going back to assets, employees, and a well-managed supply chain.

Unit economics: a Jokr case study

In early January 2022, The Information reported that Jokr was burning cash at a stunning rate even by startup standards. Internal data sent to investors and obtained by The Information showed that in August 2021, Jokr was losing $159 per order in New York City, which at that point was its only U.S. market. Jokr projected the U.S. business would lose $74 million in 2022 and $84 million in 2023, but that it would roughly break even in Latin America in 2022 and generate $76 million in free cash flow in 2023.

Shortly after The Information reporting came out, Wenzel appeared on the 20VC podcast to talk in fairly granular detail about Jokr’s unit economics. Wenzel reiterated his vision that Jokr was building a “replacement for the offline supermarket” for a younger generation of consumers that shops online, more frequently, and more spontaneously. Describing the U.S. market, Wenzel said that “instead of doing a $200 monthly grocery shopping, people will do on average $50 weekly grocery shopping.”

Jokr’s financial thesis starts with direct procurement from smaller brands and local suppliers. By directly procuring its inventory, Wenzel said Jokr is able to generate a product margin, or the amount it sells a product for over that product’s cost, of around 40% in both the U.S. and Latin America. As of January, Wenzel said about 40% of Jokr’s products were being procured directly.

I’ve summarized the rest of the unit economics in the table below (anything marked with a * is my calculation using the numbers he gave). As you can see, average order values or basket sizes are much bigger in the U.S. than in LatAm, but costs are also significantly higher. For instance, you can see the monthly lease costs in the U.S. are roughly 4-5x that of LatAm, but the margin Jokr makes on those orders after fulfillment in the U.S. is more like 2.5-3x that of LatAm. Back the math out further and you get that in a market like Mexico City Jokr can cover its monthly lease costs after anywhere from 600 to 1,300 monthly orders, depending what figures you punch in for fulfillment cost share, while in the U.S. it takes roughly 1,000 to 2,100 orders to cover that cost. That’s a much steeper bar to meet in the U.S.

This of course isn’t the full picture—one big question mark would be what Jokr spends on customer acquisition (CAC), which could definitely help to explain that $159 per order loss. I would also assume that Wenzel has given 20VC his rosiest version of the unit economics, for instance, assuming a 40% product margin on every order despite also saying only 40% of Jokr’s procurement was direct and therefore yielding that 40% product margin. All that said, the numbers give a useful glimpse of the costs that go into running an instant delivery operation, and why factors like order frequency are so crucial to the math theoretically working. Also, none of this does anything to clarify to me what Wenzel meant when he told TechCrunch in April that Jokr was “fully gross profit positive on a group level for our local business across all of our countries after 12 months of operations,” or as I call it, GPPoaGLfoLBaaooC.

The bigger picture

Jokr exiting the U.S. strikes me largely as a symbolic concession. Based on The Information’s reporting and the numbers laid out by Wenzel, it seems unlikely that Jokr had any reason to believe it could make money or even stem huge losses in the U.S. in the near future, but operating in New York and having a U.S. presence may very well have helped Jokr generate buzz and attention among U.S. investors. Wenzel said in a statement that U.S. operations have recently accounted for only 5% of Jokr’s business. It’s possible that New York and to a lesser extent Boston were an expensive advertising play to sell investors on Jokr.

Zooming out, Jokr U.S. is another casualty of a selloff in the public tech market and a private market that has suddenly soured on funding chronically unprofitable startups. As Benchmark VC Bill Gurley tweeted the other day, founders “understand that the cost of capital just went way up & that high cash burn rates are now impossible.”

Adjustment is painful. It means cost cutting, layoffs, and scaled back plans. Adjustment is Gorillas laying off 300 employees and quitting Italy, Spain, Denmark, and Belgium; Getir cutting 14% of staff globally (4,480 people and slashing spending, Zapp preparing to cut 10% of staff (200-300 people) and retrenching to London; and Jiffy pivoting from consumer-facing operations to software as a service. As I’ve said before, it’s also important to acknowledge the role of investors in getting us to this point. In the case of instant delivery, investors have thrown more than $10 billion at a space that has yet to produce any concrete evidence that it can make a profit. That money goes to dark stores and direct procurement, but it also goes to consumer subsidies (I currently have £30 of Gorillas discounts available to me, for example) and marketing promotions (I also have a giant Gorillas tote bag that every single Hackney Half Marathon finisher received a few weeks ago) and to artificially inflating demand to generate numbers that can be used to justify further investment.

This is the boom-bust cycle of Silicon Valley: investors get excited about a product or service and they throw a lot of money at it, which creates demand but also often makes the market irrational. Depending how much money goes in at the beginning, it can take years for things to get back to normal. Uber, for instance, after shielding consumers from the full price of its service for more than a decade, is finally focusing on profits at a clear cost to consumers. According to analysis from YipitData, the average price of an UberX ride before tips has risen 40% over the past three years. An Uber ride in many cities is now roughly the same price as a regular taxi. Uber is arguably too big to fail but the same can’t be said of the instant delivery players, especially with so many other delivery companies lined up to take their place. The question as always is: if the funding pipeline dries up and companies like Jokr need to start charging the true cost of their service, who will be willing to pay?

Alison, great reporting and congrats on your Half Marathon finish. Keep that tote bag... it may be worth a lot one of these days as an epochal marker of an era (hopefully) long gone.

As for Mr. Wenzel, quite the achievement to have left his blitzscaling mark on the trifecta of WeWork, Oyo and Jokr. I'm in absolute awe of Ralf's accounting audacity. Jokr's GPPoaGLfoLBaaooC makes WeWork's Community Adjusted EBITDA look downright puritanical.

I wonder if the hucksters who assured us that a new generation consumers don't have the patience to ___ {FILL IN THE BLANK}, bothered to ask whether this new class of privileged consumers are able and willing to pay the full cost for the luxury to not have to COOK, SHOP, or WAIT FOR ANYTHING.

Dutch-based Picnic is a refreshing reminder that faster isn't always better, particularly if a more deliberative approach allows a transformational restructuring of the entire grocery supply chain. Maybe the focus of your next foodie story?