One big question for micromobility

This is the framework for all other debates about "shared" bikes and e-scooters

On Monday I gave a “state of the industry” presentation at a shared micromobility event hosted by the National Association of City Transportation Officials. The audience was largely local officials involved in the on-the-ground administration of bike and scooter contracts in their cities, so I focused on the big picture: the role of startups and venture capital in the creation of a new mode of urban transport, and the tension between public and private in public-private partnership. Today I’m sharing the full presentation exclusively with paid Oversharing subscribers.

I call this the One Big Question because it frames every other element of the debate about “shared” micromobility services like bikes and scooters. How much should they cost? Should they be docked or dockless? How much do we care about equity and accesibility? Should these services turn a profit or rely on subsidies? Your answers to each will depend first on your answer to that one existential big question.

We talked last week about the phrase “sharing economy”: where it came from, how it evolved, and why it’s a misnomer. Bike and scooter services are also often branded “sharing.” Bike-share, shared scooters, etc. “Sharing” in this case is used in contrast with private ownership—shared micromobility refers to the use of a bike, scooter, or other lightweight vehicle that belongs to a third-party fleet rather than you personally. That’s a stronger case for sharing than many companies in the space can make, but ultimately these are still for-hire services leaning into the consumer-friendliness of the “sharing” ideology. It’s why I prefer other phrasing, like Transport for London’s descriptions of Santander Cycles (“Boris Bikes”) as “cycle hire” and scooter fleets as “rental electric scooters.”

The full presentation is available exclusively to paid subscribers. To unlock 🔓 the rest of my state-of-the-industry slides and commentary, upgrade your subscription today.

The biggest players in the industry subscribe to Oversharing. Expense a group subscription for your team to keep up with our latest coverage and ground-breaking analysis.

Hello 👋 paid subscribers! The rest of this post is just for you. Let’s get back to it.

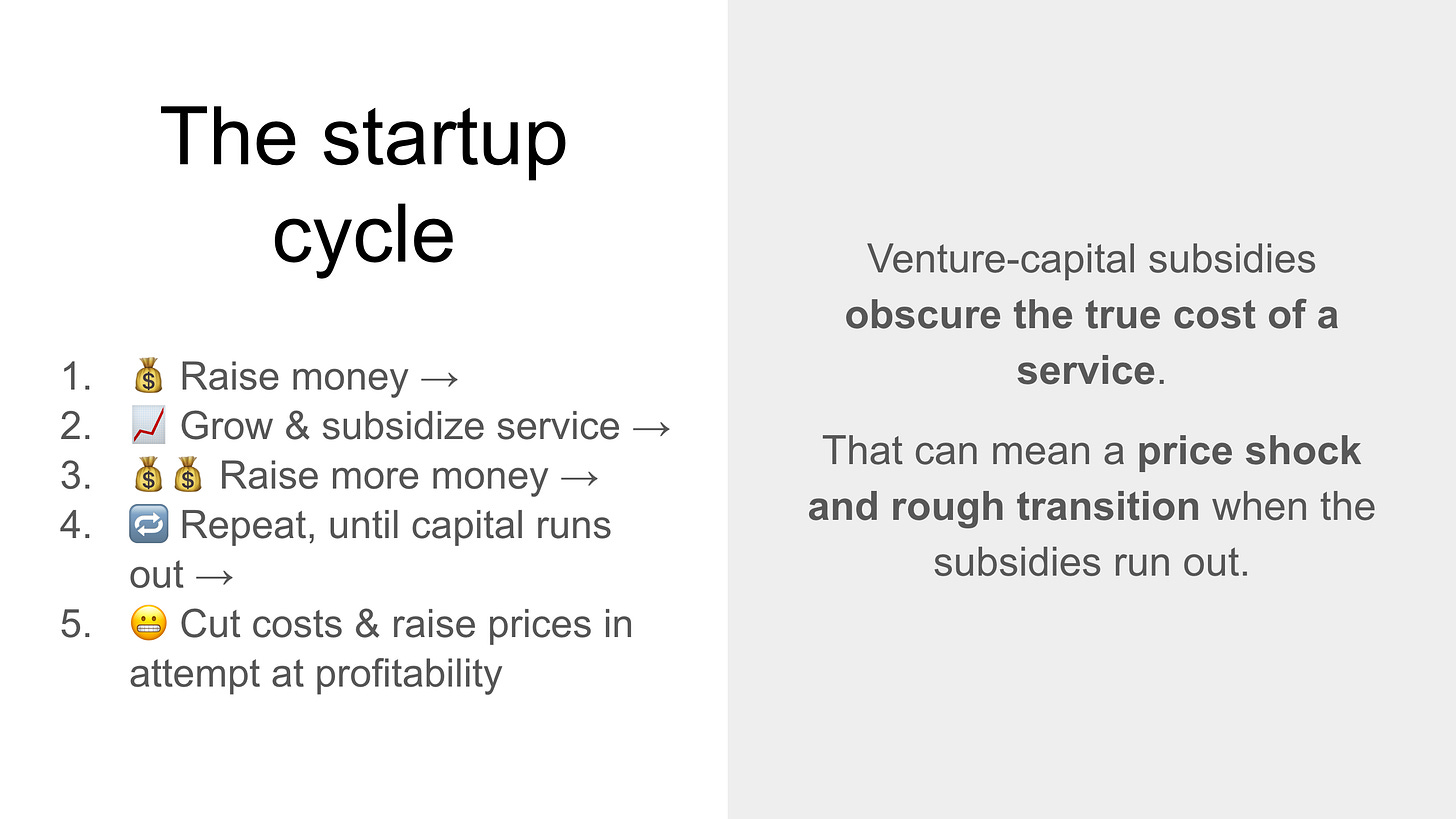

Anyone working on the procurement of urban services should have a basic understanding of the startup cycle, especially if any of their providers are VC-funded. The most basic startup cycle has three steps:

💰 Raise money

📈 Grow the service

🔁 Repeat

There are a lot of different ways a startup can accomplish step 2, but a common strategy is subsidies. These can take different forms, for instance, coupons, referral codes, signup bonuses, and limited-time discounts. However you do it, the goal is to get new customers in the door and using the platform, with the hope that they’ll like it and stick around.

Subsidies can be very effective. I still go to a hairdresser in London who a friend referred me to with a 20% off coupon when I first moved here. The discount + recommendation from a friend got me in the door, and the quality of the service kept me coming back, even at a higher price point.

Where startups tend to run into trouble is when they become overly reliant on subsidies. They sell a service, but they’re always selling it at some form of discount, and the price of the service doesn’t actually cover the costs of running it. That means 1) those companies need to keep raising more funding from VCs and 2) over time, they teach customers to expect to have this service at an unrealistic price point.

I talk about subsidies a lot in context of ride-hail. Uber and Lyft spent years competing on price for both riders and drivers. They gave riders discount codes and referral schemes and drivers lucrative signup bonuses and incentive pay. They lost a lot of money doing it, and eventually something had to change. For drivers, pay rates dropped, bonuses became fewer and farther between. For riders, the dirt-cheap on-demand rides that once defined these services have largely become a thing of the past.

Because that’s the thing about subsidies: someone has to pay for them. For startups, this is usually venture capital. Micromobility has seen a lot of money floating around. Startups offering rental bike and scooter services in the U.S. have raised at least $3.8 billion from private investors, according to data from PitchBook. Lately though, funding has been harder to come by. That’s when things tend to get messy.

Micromobility startups have recently cut jobs, closed offices, exited markets, and even put their businesses up for sale as capital has become harder to come by. European e-scooter startups Tier Mobility and Voi have each laid off more than 100 workers in the past six months, with Tier also cutting staff and downsizing office space at subsidiary Spin. Tier is now reportedly up for sale, with tech news site Sifted reporting it could be scooped up by European rival Bolt “in weeks.” The pain has also extended to the public markets. Bird Inc., the original dedicated e-scooter startup, sold itself to Bird Canada in December after its financial situation grew so dire that its co-founder put his Miami mansion on the market and the company started sending threatening emails to customers with unpaid account balances in the pennies. Lyft, which along with ride-hail operates many of the biggest U.S. cycle-hire programs, plans to cut 26% of staff, leaving the future of those cycling schemes in doubt.

This brings me back to our One Big Question! Should micromobility services be for-profit travel or an extension of public transport? If the former, then at some point they must overcome their reliance on subsidies and start to make money. If the latter, subsidies forever, because most major public transport systems lose money by design. That’s the thing about public transport—they are services for the public, funded by the public. As you can see in that BBC graphic above, not only do most major global metros rely on some form of taxes or subsidies, they rely on it for more than half of their financing. London’s Tube is actually an outlier in that nearly three-quarters of its funding comes from passenger fares (and before covid-19 hit, it was even briefly on track to turn a profit).

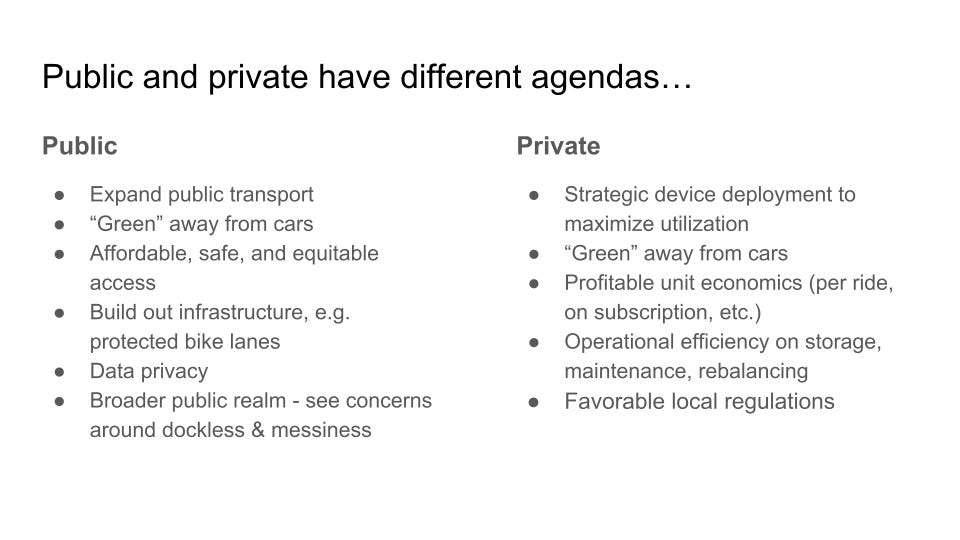

Micromobility companies like to talk about “solving the first and last mile” and “integrating into public transport.” But the reality is that so long as these services are run by private companies, the goals of the companies will be on some level in tension with the goals of the public. The problem with public-private partnerships is that even when the two sides have a lot in common, the public side answers to its citizens and the private side to its shareholders.

That’s not to say partnerships are bad. The opposite, in fact. Both public and private sometimes need things from the other that can best be solved in partnership. In the case of micromobility, cities offer companies a crucial urban laboratory to test their services (a term I’ve borrowed from this 2017 paper by Federico Caprotti and Robert Cowley). Companies, for their part, take on the risk of testing out a novel service. Setting up a micromobility service requires a big initial capital investment to purchase the fleet, develop the software, and hire and train the team that handles the day-to-day operations. Governments tend to be risk averse and slow to allocate funding, meaning without involvement from the private sector, something like an e-bike or e-scooter service would be unlikely to ever get off the ground.

This is more or less what we’ve seen with micromobility. Private companies have come into cities and introduced them to a new mode of transport. They’ve put up the money to create the fleet, develop the software, hire the ops teams, and develop a user base. The cities, after initially being flooded by these new devices, have responded with contracts and permits to regulate the process and work toward some of their own goals of fairness and equity. The formalization of this partnership through RFPs has brought a degree of stability to the sector, but also underscored its tensions. Private companies that made that initial investment now reasonably want a chance to earn it back. Cities are seeking more control over their public rights of way and safeguards to ensure vendors hold up their end of the bargain. No one has figured out what to do about dockless clutter.

There’s nothing wrong with companies wanting to make money, just like there’s nothing wrong with governments wanting to serve their constituents. But sometimes the two conflict. So long as micromobility is run in partnership, that tension will be there. The real question is what we want these services to be: privately funded accessories to urban transit, or a true integration into public transport? The answer will shape micromobility for years to come.