Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning, thanks! If you’re new, it’s great to have you. A special thanks to all the paying subscribers whose support makes this newsletter possible.

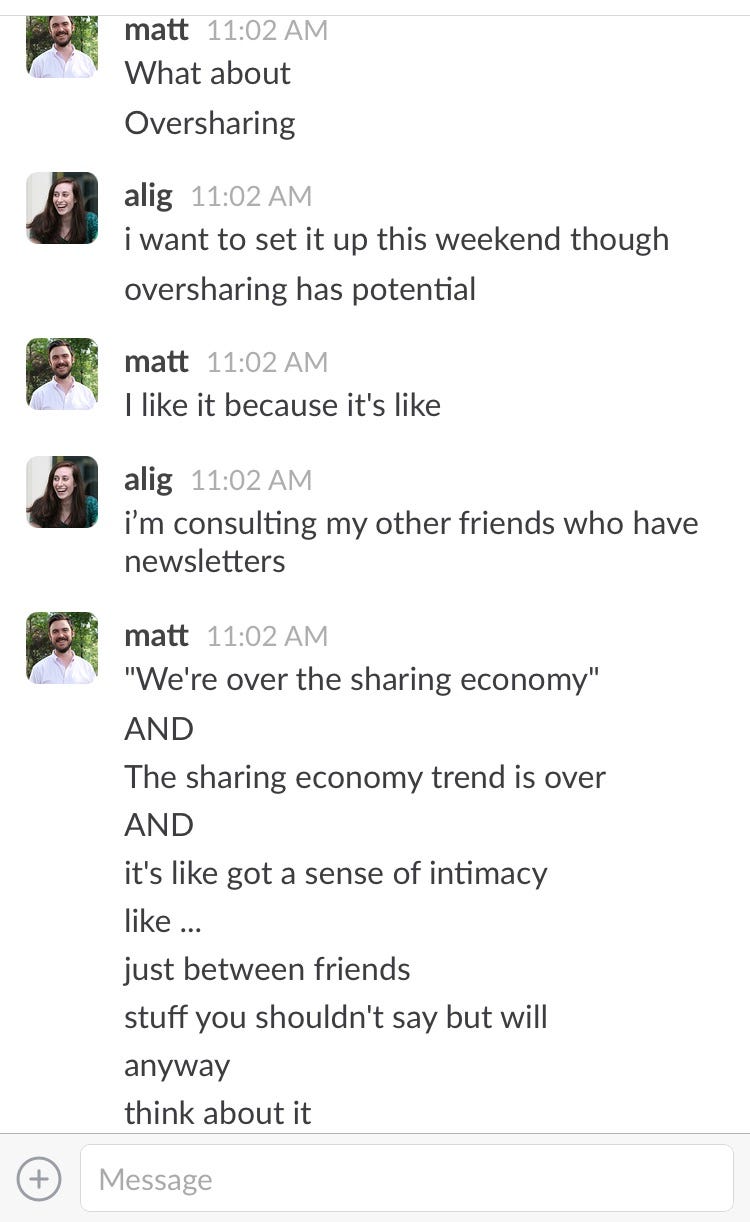

The name for this newsletter came from a brilliant former editor of mine, Matt Phillips. I knew I wanted to launch a newsletter about companies like Uber and the broader phenomenon of gig work, but was struggling to think of a name that hit the right notes of informative, savvy, and whimsical. I had bounced a couple possibilities off Matt, none of them very good, when one day he messaged me:

Oversharing. We’re over sharing. We’re oversharing. Matt was right. It was perfect.

In the past decade, the terminology for the space has evolved, from “sharing” to the more apt “gig” economy. “Sharing” emerged with the earliest version of this economy, in which new online platforms formalized the peer-to-peer sharing of spare assets or time. The original sharing economy platforms were true sharing. A classic example is CouchSurfing, a website founded as a nonprofit in 2003 that let people offer free lodging in their homes to (brave, trusting) travellers.

The next phase of sharing was the one that went big. Uber, Airbnb, Lyft, Instacart, TaskRabbit, DoorDash, Postmates, and so many bygones. Airbnb embraced the language of sharing from the beginning. The Airbnb origin story is that co-founders Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia needed money to pay rent on their San Francisco apartment, so they rented out air mattresses to designers coming for a local conference. Airbnb was soon marketing the idea that anyone could earn a little extra income to help make ends meet by “sharing” space in their home.

Uber had less humble beginnings. Co-founders Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp dreamed up the idea for an on-demand private car service after trying and failing to get a cab one snowy night in Paris. The service launched in San Francisco as “UberCab,” a convenient luxury alternative to taxis, before dropping “cab” from its name in 2011. “UberX,” the cheaper, peer-to-peer rides product that took Uber from “everyone’s private driver” to global “ride-sharing” sensation, rolled out a year later.

These poster children of the new digital economy talked of “home-sharing” and “ride-sharing,” but charged for it. “Sharing” no longer accurately described the marketplace, but remained a convenient shorthand for talking about app-based technology platforms that facilitated either the peer-to-peer rental of assets (homes, cars, gardening equipment, etc.) or the peer-to-peer hire of labor (for a ride, a delivery, a babysitter, the refueling of your car, etc.). The “sharing economy” was a misnomer, but a catchy one, so it stuck.

In the years since, academics have proposed various alternative language to describe this space, none of it quite right. The collaborative economy. Platform work. The 1099 economy. In his 2016 book The Sharing Economy, NYU Stern School of Business professor Arun Sundararajan broadly employs the term “crowd-based capitalism,” which he argues “spans the market-to-gift spectrum.” In the hospitality sector, for instance, Sundararajan suggests Couchsurfing falls on the gift end; Airbnb sits in the middle, thanks to the reviews process and “intimacy” of staying in someone’s private home; and luxury vacation rentals platform OneFineStay is on the purely market end.

Others have distinguished between platforms renting capital assets and selling labor. Capital vs. labor is the simplest line to draw between “sharing” and “gig.” Sharing requires first having something to “share” (a room on Airbnb, a car on Turo), while gig demands only the willingness to take on ad-hoc jobs through digital platforms (driving for Uber, delivering on Grubhub, cleaning homes on Handy). Some of the earliest research on the sharing-gig economies focused on the capital-labor divide, noting that the asset-renters typically earned surplus income from their activities, while the gig workers turned to digital platforms to fill financial gaps.

It’s been a long time since “sharing” meant sharing. Silicon Valley redefined sharing to mean something like “using a technology platform to get more use out of something you already have.” By the same logic, you could call restaurants shared dining rooms, gyms shared fitness spaces, libraries shared bookstores (jk, libraries are real sharing! Support your local library!).

What sharing has actually meant in practice is the formalization of services through trust credentials and risk management. People were selling rides and renting out rooms long before Uber and Airbnb, but the platforms created systems that allowed this to happen at scale and with some degree of accountability. Reviews made it easier for strangers to trust each other in the one-off fulfillment of services. The platforms set up insurance to protect drivers and homeowners from the potential liability involved in offering rides and renting out homes. I sometimes joke that the only thing the sharing economy really shares is liability; the reality is that the sharing of liability is an essential pillar of what these platforms offer and why they work.

I started writing this essay in response to the news that Lyft, the original seller of “shared” rides, is getting out of the shared rides business. “The problem with shared trips is that they take people out of their way,” new CEO David Risher told Bloomberg yesterday. “At some point you have to pay attention to what your customers want.” Why Lyft has actually abandoned the pooled rides it once cherished is a topic for another day. The point for now is that while “sharing” has been over in practice almost since it began, Lyft’s choice to abandon shared rides in favor of its bottom line signals a symbolic end to the sharing discourse—that we are finally over “sharing.”