My year as a Substack Pro

After years of writing about venture capital subsidies, I secured one myself

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning, thanks! If you’re new, it’s great to have you.

I started Oversharing as a side-gig to my staff journalism job back in 2016. I ran it for several years, then took some time off from writing during the pandemic. It’s been just over a year since I relaunched Oversharing with more issues and paid subscriptions on Substack. This month, Oversharing hit another milestone: fully subscriber-supported status. That’s because for the past year, Oversharing was supported a bit by paying subscribers and a lot by a subsidy from Substack. I’m going to tell you more about that now.

Last year, I took a deal as a Substack Pro. If you follow Substack or the media sphere, you may have heard of Pro, a program in which the company pays yearlong publishing advances of varying sums to newsletter writers in exchange for the bulk of their subscription revenue. Early Substack Pros included culture writer Anne Helen Petersen of

and contrarian blogger Matt Yglesias of . (Fun fact: Slate initially hired me as one of two people to replace Yglesias, who had held down Slate’s business and economics coverage all by himself.)While Substack Pro isn’t exactly a secret, Substack didn’t publicly acknowledge it until 2021, when the news that it had paid six-figure advances to writers like Yglesias started circulating alongside accusations that Substack was actively supporting fringe and anti-trans personalities via the Pro program. Content moderation is an age-old dilemma of online platforms (👋 there, section 230), but Substack added a new twist in not just hosting a platform on which anyone could publish, but actively recruiting and subsidizing certain writers. Controversy rarely breeds openness, and even today, Substack still doesn’t disclose who on the platform is a Pro or how many it recruits.

Substack first offered me a Pro deal in 2019. I think that’s important to note because it’s one data point that counters the narrative of Substack at first only offering these deals to big-name white guys. I was also recruited early with a six-figure offer, but for various reasons it wasn’t a good time for me. A few years later, in spring 2022, it suddenly was a good time. I had finished a mid-career master’s program, and like many others was adjusting to post-pandemic life and looking for the next thing. When Substack expressed interest in having me relaunch Oversharing full-time and with paid subscriptions as a Substack Pro, it seemed like an obvious decision.

As a Pro, I received a publishing advance from Substack (the company calls this a “grant”) in quarterly installments. Substack collected 85% of subscription revenue from Oversharing, and I got what was left after payment processing fees. The contract made clear that I was an independent writer, with full control of pricing, publishing schedule, editorial decisions, and other key aspects of the work. When at one point I absentmindedly referred to the Pro terms as an ‘employment contract,’ the legal team hurriedly replied that it was “not an employment agreement - that isn’t our arrangement with writers.” I assured them that I understood: I wasn’t an employee nor was Substack an employer, it was merely a technology platform connecting people who wanted to write newsletters with people who wanted to read them. I once said this exact line with a very straight face to someone at Substack, who, completely missing the joke, nodded enthusiastically and agreed.

I think of Substack Pro as Substack’s version of venture capital investing. It’s often said that 90% of startups fail, which is exactly how the system is designed. The VC model assumes that most investments will perform poorly, a handful will break even or do modestly well, and a select few will become wildly successful. As long as you get those few bets that pay off big, the rest don’t really matter.

The same theory applies to newsletters on Substack. While Substack hasn’t yet shared its finances in detail, there’s enough info out there to make some educated assumptions, including that Substack makes a significant chunk of money from a handful of very successful newsletters. Pro makes sense if you think of it like Substack’s in-house VC fund. It’s worth throwing grants at a group of promising writers, knowing that most of them will break even or operate at a loss, if what you’re really searching for is the next big win.

Some rough math bears this out:

In November 2021, Substack said the top 10 publications on its platform together generated more than $20 million a year. If you assume a standard 10% fee, then Substack was getting at least $2 million in revenue from just 10 newsletters.

In the year ended Dec. 31, 2021, Substack generated $11.9 million in gross revenue

$6.3 million of that came from standard 10% fees

$5.5 million came from the increased fees Substack takes on newsletters like those in the Pro program

Combining the first two points, you can assume at least 17% of Substack’s 2021 gross revenue—and perhaps a third of non-Pro revenue—was generated by just 10 publishers

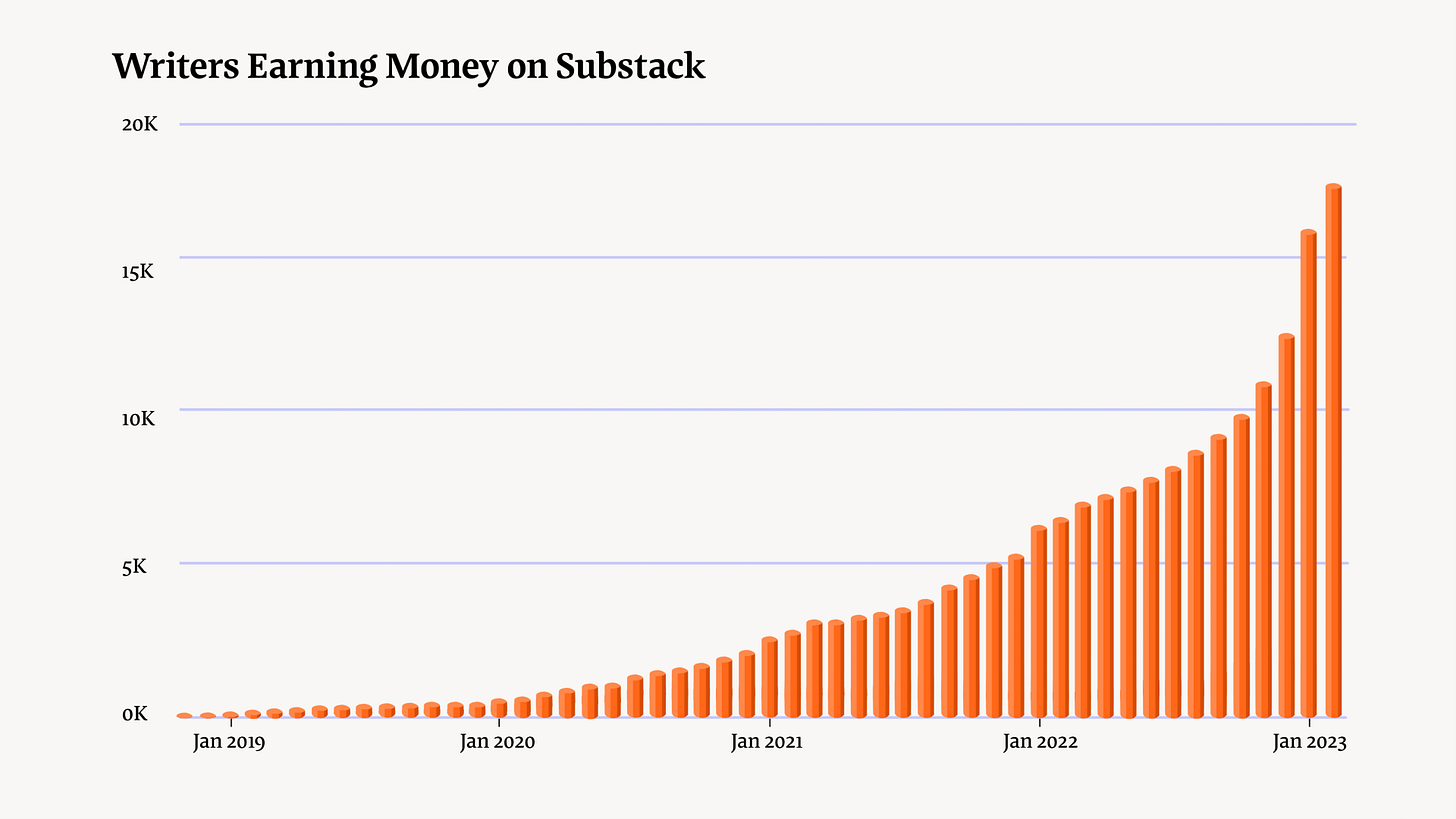

As of December 2021, there were just over 5,000 writers “earning money on Substack,” according to a chart the company shared recently. If you do some rough math again, there would have been $63 million in subscription revenue from standard newsletters in 2021 and $6.5 million from newsletters on Pro deals. You can back that out to say that if 10 publications together earned > $20 million that year, then the other 5,000ish split the remaining $49.5 million, an average of about $10,000 each (but it’s surely not an even breakdown).

I’m telling you all of this to point out that there’s a big difference between the super profitable, top-10 Substack newsletters, the others in their league, and everyone else. In a lot of ways, it’s a classic long tail business model. If you’re Substack, you certainly don’t want to discount the long tail—having more people writing and reading and subscribing on your platform is only a good thing, especially if you can get some network effects going—but a lot of the money is in those rare smash hits that top your revenue charts. And if you have tens of millions of dollars in venture capital funding yourself, why not spend some of it trying to find more big hits?

That is presumably the question Substack is asking itself now, after a year in which spending on “partnership expenses” (Pro deals, etc.) ballooned so much that it pushed the company’s total revenue into the red. Overall for 2021, Substack reported revenue of -$5.2 million. This was largely thanks to the $16.7 million Substack paid to writers that year in advances/grants, and which it booked as a deduction from gross revenue, also known as contra revenue. Negative revenue is the sort of rare financial accomplishment you only tend to hear about in Silicon Valley. Substack’s net income for 2021 was -$22.9 million, ten times its loss from the previous year.

Oversharing didn’t earn back its Substack advance. Such is the nature of VC-funded subsidies. But Pro isn’t just about the financial calculus. It’s also about helping more people get going with full-time independent publishing, a leap that can be scary, especially if taken from traditional employment. I’m grateful to Substack and its VC backers for giving me the financial cushion to explore and experiment with Oversharing for the past year on my own terms. I also appreciate the irony that after making a career out of writing—sometimes snarkily—about startups that rely on venture capital subsidies, I spent a year running a business off my own indirect VC subsidy.

The difference is that my subsidy was always time-limited. My year on Substack Pro ended in March. I’ve now embarked on the next phase of seeing if I can make this newsletter work as a solely subscriber-supported publication. As such, I’m making some changes. I’ve dropped the monthly price to an accessible $6 (what I like to call ‘half a glass of wine in New York City’). I’ve also created a “founding member” tier for Oversharing superfans—if you really love the newsletter, you can pay a higher rate to show your support.

Since I started Oversharing more than 7 years ago, I’ve published it more or less once a week for free subscribers. I kept that going over the past year—once a week for everyone, other issues for paying members—but it’s become clear that doing so removes much of the incentive for people to pay. Going forward, Oversharing will be free only intermittently. I don’t love this. I mean, I’m a journalist! I like to share information, and I certainly didn’t choose this career to get rich. But I also need to earn a living. More than that, my work is really fucking good. I initially wrote that sentence as “I believe my work is really fucking good” but to paraphrase a wise friend, “I believe” is couched female language. Just say I am, I do.

The tragedy of modern journalism is that for the most part it attracts smart, public-service minded people who do good work and expect very little in return. The pay is bad, the working conditions are mediocre, the career ladder barely exists. You are frequently reminded of how your job is prestigious, how you’re lucky to have it, how you could be replaced in an instant. The journalism business model broke a long time ago and we have yet to fix it. That break created space for Substack and other platforms that promote their products as a better way for writers, thinkers, analysts, and creatives to earn a living from their work.

Whether this is actually the case still has very much to be determined. There are certainly some incredibly successful people on Substack, in that top 10 and beyond, but there are also signs that the formulas that work well in other online media—click bait, hyperbole, outrage, pseudo-intellectualism—sell newsletter subscriptions too. It’s not lost on me that the business and technology categories on Substack are dominated by men, many of whom have perfected a particular type and pace of writing and self promotional analyst-speak. There is a formula for success, and the people who follow it have been able to do very well.

Oversharing doesn’t follow that formula. I don’t publish as much as some newsletters because I only want to publish when I have something genuinely interesting and insightful to say, and honestly that doesn’t happen four times a week. I’ve also never been much for self promotion, or for pretending like I know everything. There are some things I know a lot about and feel comfortable offering an educated perspective on—the math behind the earnings floor for New York ride-hail drivers, the political evolution of the Uber playbook—but even with those things I’m sure there’s more to learn. Oversharing is as much about my learning as yours.

I love Oversharing and this community. It’s also a lot of work and time, and my work and time are valuable. That’s something journalists are taught not to think about so it can feel uncomfortable to say it, but it’s true. My work is valuable, my insights are valuable, this newsletter is valuable. I know that because of how many of you who read and share it regularly work in and around the gig economy. How many of you write to tell me so. I’ve heard how Oversharing has expanded your thinking about the services you use, the jobs you do, the world we live in. And I’m really glad for that. I’m glad to have you here, as a reader. What I’m asking now is that you show that support in another way, and become a paid subscriber.