Utilization rates.

“For the 60 percent-plus of all New York City drivers who are full-time drivers—and who provide 80 percent of all rides—work hours are not flexible,” begins this report on ride-hail driver earnings, thus neatly dispensing with the myth that Uber drivers in New York can be their own boss and work their own schedule. The July 2 report was commissioned by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) in response to concerns about the low earnings and high operating costs—all in all, the heavy financial burden—faced by the typical driver in the city today.

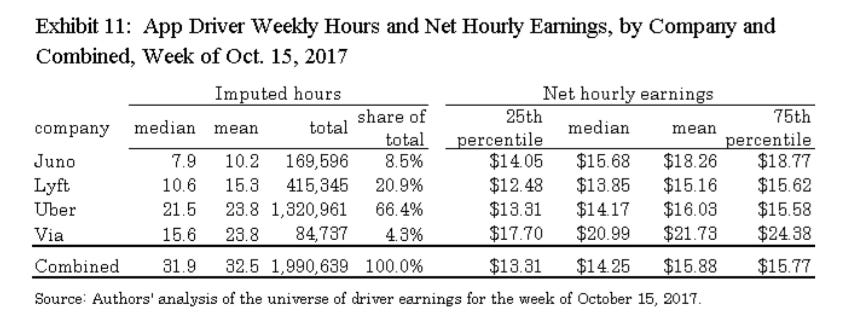

The report, written by James Parrott of The New School’s Center for New York City Affairs and Michael Reich of UC Berkeley’s Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics, proposes setting a wage floor of $17.22 an hour. The goal is for drivers to take home $15 an hour after expenses like gas, maintenance, and other vehicle costs. This would represent a 22.5% bump in net earnings, or an increase of $6,345 per year on average, according to the report, which estimates that 85% of drivers currently earn less than $17.22 an hour. (Via, an exclusively shared rides app, is the only company that consistently pays drivers above that threshold.)

There are now 80,000 vehicles in New York City that provide app-based rides, more than five times the 13,587 medallion taxis. Those ride-hail vehicles complete more than 17 million trips a month, double the number of medallion trips.

New York City has previously tried to cap the number of drivers working for companies like Uber to no avail. In the famous cap fight of summer 2015, the de Blasio administration proposed all but stopping Uber’s growth in the city in order to study its effect on congestion. The proposal was poorly thought through and Uber campaigned aggressively to defeat it, delivering a stunning rebuke to de Blasio and city council.

What does that mean? You can think of utilization as the share of time that an Uber driver has a rider in the car, compared to hours spent logged into the app but commuting to and from home, cruising for a fare, or driving to pick up a passenger. Parrott and Reich propose that each company be given a utilization rate, as measured by the TLC in the previous quarter. In 2017, the TLC calculated Uber and Lyft had utilization rates of 58%, Juno of 50%, and Via of 70%. That rate then gets plugged into a formula that sets per-trip driver pay based on minutes and miles:

In October 2017, researchers at Uber produced a paper in collaboration with John Horton at NYU Stern that asserted that Uber was effectively powerless to raise driver wages. The reasoning went like this: Anyone can drive for Uber, when and for however long they like. If Uber were to raise its rates, supply would swell because more people would work more hours, while demand would stay the same or fall, as riders would likely be deterred by higher prices. The result would be less work to go around, such that drivers would make more per trip, but get fewer trips and not earn more overall.

The great irony of this paper was that if you inverted the framing, it was the best possible argument for capping the number of Uber drivers on the road. The core assumption of the paper—the reason why Uber simply couldn’t pay drivers more—was that the ride-sharing market “is highly elastic,” with existing drivers facing “no quantity restrictions on how many hours to supply” and new drivers facing “minimal barriers to entry” (that is from the abstract). How do you change that? You make the market less elastic. You start to limit supply, and suddenly wages can rise.

This is not a new realization. New York City created the taxi medallion system in the 1930s precisely because too many drivers were chasing too few riders, leading to long hours and unlivable pay. That solution then became the problem, as demand quickly outgrew supply and the number of taxi medallions remained relatively stagnant. You know the rest of the story: Uber arrived, shattering the monopoly. Fares fell, medallion prices plummeted, and the number of drivers available at the touch of a button soared.

Parrott and Reich aren’t proposing a return to the antiquated medallion system; they are offering something better. By incorporating utilization into the pay formula for drivers, they create a flexible and natural cap, one that rewards companies for having supply match demand. Uber can flood the market with drivers whenever it wants, but if the market doesn’t need them, then Uber, not its drivers, will pay.

More bikes.

Lyft has bought the bike-share programs operated by Motivate, a deal rumored to be in motion a month ago. That means Citi Bike (New York), Capital Bikeshare (Washington DC), Ford GoBike (San Francisco), Blue Bikes (Boston), and many other locally branded bike shares will now be owned by Lyft instead of Motivate.

Motivate is the clear leader in US bike share programs, claiming 80% of all bike share trips in the US in 2017 were taken on systems it operated. But it is also something of an outlier in our current era of dockless everything. Rather than floating haplessly around city streets and sidewalks, Motivate’s bikes mostly live in orderly docks spread stationed throughout its markets.

Dockless bike share startups have so far proven more controversial in cities—partly because people steal and vandalize them, park them on sidewalks, and toss them into lakes—and are still trying to figure those relationships out. By buying Motivate, Lyft gets a program that already has the legitimacy of contracts and relationships with cities. That should make it easier for Lyft to get into dockless bike share too, should it wish. At the same time, it’s unclear how long those contracts have left, and whether they’ll be able to withstand the many well-funded bike and scooter startups.

Elsewhere, here are some thoughts on the deal from a bike-savvy Oversharing reader:

In terms of the acquisition, it'll probably take awhile to close before we really see the impact Lyft will have. The big question I have is why, because Motivate's bike share operations are a known money-loser, and Lyft isn't going to be making money any time soon. What they do get is 1) a shit ton of data (just think about all those Citibike trips) and 2) pre-existing, positive relationships with cities, because all the cities see bike share as this great win-win.

Scooters!

I love this headline even more because it is in the Financial Times:

Here is my Quartz colleague Josh Horwitz, who was all over the scooter tariffs before the FT:

If a scooter currently costs each company $400 to purchase, a 25% tariff would raise the company’s final cost to $500. To offset the increase, startups will likely have to charge consumers more money per ride, dig deeper into their VC-funded coffers, or both.

Those cheap rides could be gone sooner than you think.

Other stuff.

Anthony Levandowski is back. Airbnb Promises More Cash for Employees, Plots IPO by 2020. Go-Jek seeks $1.5 billion to take on Grab in Southeast Asia. Lyft raises $600 million. Con Artists Are Fleecing Uber Drivers. How Uber’s Self-Driving Car Unit Plans to Move Forward. Uber launches Jump Bikes in Austin. Uber prepares subscription e-bike service. Ride-hail may benefit poor and low-income neighborhoods most. Amazon needs more delivery drivers. Tesla loses key engineer. Uber applies for patent to route users around unsafe areas. The SEC Has Its Own Questions About LaCroix. Postmates gun arrest. Electric vehicle war. The Math Behind “Bus Benching.” “It’s Burning Man in Chelsea.”