Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. This late edition brought to you by New York governor Andrew Cuomo’s “State of the State” and budget address, which brings us to…

Congestion pricing.

How do you get people to use cars less? Try making driving more expensive.

Support for congestion pricing, a tax designed to mitigate traffic by charging motorists to enter crowded zones, is at a historic high in New York, according to a recent Siena College poll of 805 registered New York state voters. Statewide, New Yorkers support a congestion pricing plan to reduce traffic and pay for subway improvements by a 52%-to-39% margin.

Support for congestion pricing outweighs opposition across almost every demographic. Liberals, moderates, New York City, suburban households, upstate, white, black, latino, every age group, every religion, every income level. Only conservatives and, interestingly, union households are more likely to oppose the measure than to support it. Support was particularly strong among black (64%) and latino (57%) respondents, as well as among people ages 18 to 34 (63%) and people earning less than $50,000, the lowest income bracket (60%).

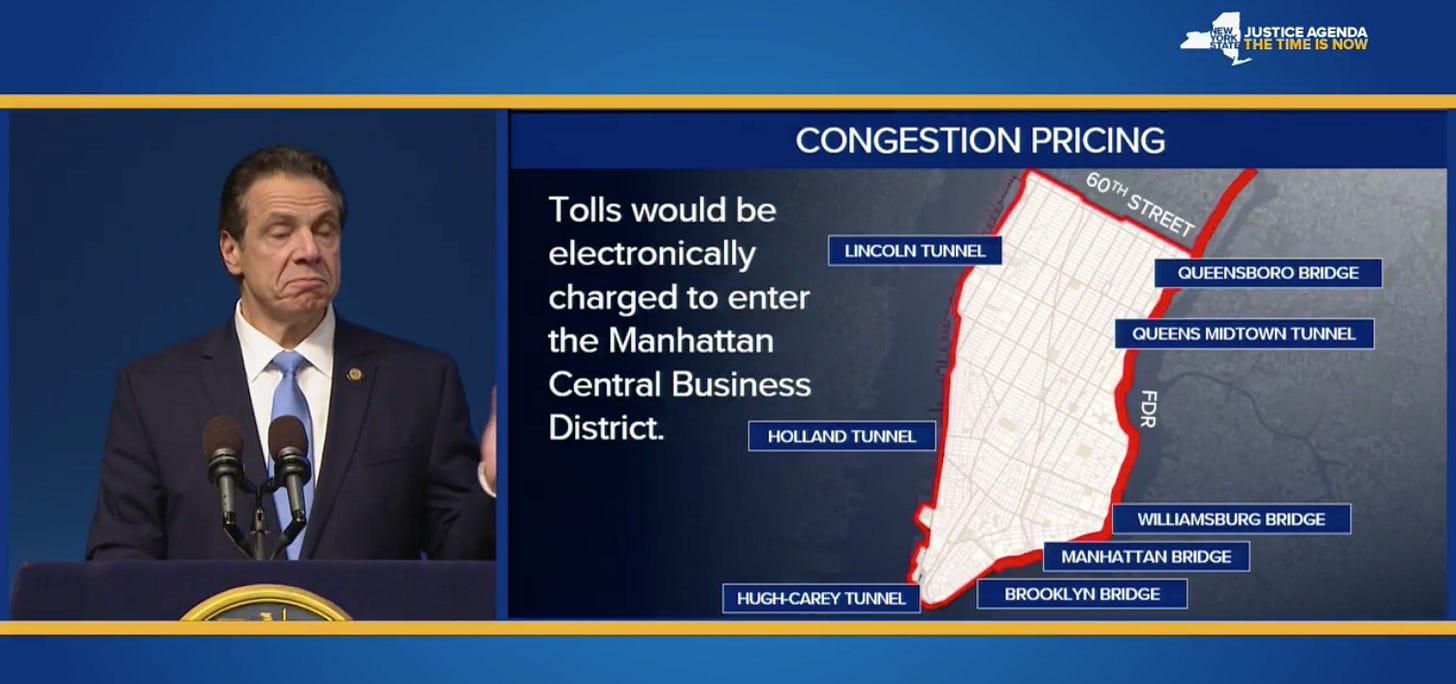

Only about 10% of voters hadn’t heard of congestion pricing or had no opinion on it, setting up Cuomo nicely to propose a congestion pricing plan in his 2019 “State of the State” address this afternoon. Cuomo proposed a fee to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street. The fee, Cuomo said, would create “toll equity” by ensuring drivers paid to enter the busiest part of Manhattan, regardless of where they came in. The exception would be for drivers traveling along the FDR Drive, on the east side of the city, to go north or south in Manhattan.

Here is a quality screenshot of Cuomo talking about the plan while closing his eyes and making a face:

Vehicle speeds in the Central Business District have been dropping since 2010, most recently to 7.2 miles per hour. Cuomo’s office pointed to “remarkable growth of for-hire vehicles in New York City”—here’s looking at you, Uber—plus new bike lanes, pedestrian plazas, deliveries, and tour busses. Construction, of course, also factors in. Uber policy manager Josh Gold said in a statement following Cuomo’s address that the company supports congestion pricing for “all users of Manhattan’s congested roads.”

A mini-congestion surcharge on for-hire rides in Manhattan south of 96th Street was supposed to take effect in January, but remains on hold after cab drivers sued. That plan would add $2.50 to taxi rides, $2.75 to other black car trips and private rides booked through an app, and $0.75 for shared ride-hails, like UberPool or Via. Shared rides, in other words, get a big break.

Cuomo’s congestion pricing plan would apply to all vehicles and is projected to raise $15 billion, but it wouldn’t take effect until 2021, which feels like an awfully long time when measured in minutes-spent-waiting-on-a-stalled-subway-car. That $15 billion also represents only a quarter of the estimated $60 billion needed to rehab the city’s subway system, and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio remains opposed to Cuomo’s plan for the city to split the cost of a shortfall 50-50. “If anyone thinks that money can be found in the city budget, they may be smoking marijuana,” de Blasio said yesterday—something else that could soon be legal in New York, if Cuomo gets his way.

Congestion pricing or a cordon toll is popular among transit wonks but historically has been politically unviable in New York and the rest of the US. Vehicle owners understandably chafe at the idea of having to pay even more tolls to get where they need to go, particularly if the toll is getting tacked onto a regular commute to work. A congestion plan proposed by former New York City mayor Mike Bloomberg in 2007 met a quick death in Albany.

But congestion pricing works in cities that have implemented it, such as London and Stockholm. Vehicle speeds rise, and congestion and carbon emissions fall. “If you survive this valley of political death, and people actually see the benefits, and also realize that, in addition to the benefits, it’s actually not as bad as you thought—it’s not so hard adapting to this—then support starts going up again,” Jonas Eliasson, Stockholm’s director of transportation, told Curbed in March 2018.

Despite the support in New York, enacting congestion pricing remains an uphill battle. But it's a far more achievable and implementable fix to a city's traffic woes than waiting around for a hyperloop, or fully autonomous driverless cars, or flying taxis, or any of the more fantastical solutions being worked on in Silicon Valley. Those moonshots may happen one day, but in the meantime congestion pricing can hasten the car's exit from the American lifestyle.

Scooters!

They could also be coming to New York state, per a section in the freshly released executive budget. A “locally authorized scooter” is defined as a “two-wheeled device that is no more than forty-one inches in length, seventeen inches in width, and forty-five inches in height, which does not have a seat or saddle, is designed to transport one person standing on the device and can be propelled by any power other than muscular power.” In other words, a stand-up electric scooter, but not a moped.

These locally authorized scooters would be permitted to operate on roads with a speed limit of 30 mph or less, including designated bike lanes. One hand on the scooter at all times, must be 16 years of age or older, yield to pedestrians, ride single file, no drinking and scooting, speeds limited to 20 mph on roads and 8 mph on sidewalks (if local rules permit). You know, standard stuff. Oh and my personal favorite:

No person shall operate a locally authorized scooter outside during the period of time between one-half hour after sunset and one-half hour before sunrise unless such person is wearing readily visible reflective clothing or material which is of a light or bright color

I mean just imagine the ticket exchanges:

NYPD: Do you know what we pulled you over for?

Scooter rider: Er, no, was I speeding?

NYPD: No, you were operating in the one-half hour after sunset

Rider: I… er… is that not ok, officer?

NYPD: AND YOU ARE WEARING BLACK

Rider: Well, uh, yes, it is New York City…

NYPD *scribbles ticket*: Drive safer next time.

Key details.

Montreal’s new policy is if-you-see-something, say-something policy, when it comes to Airbnb. City mayor Valerie Plante is urging residents to report any lock boxes they spy attached to public property, like parking meters or bicycles. Local officials believe such lock boxes are the latest attempt by Airbnb hosts to dupe enforcement efforts, by making it harder to tell which properties are being rented on the home-sharing site, and recently directed city inspectors to cut down any lock boxes they spotted clinging to public property. “Our teams are at work,” Plante tweeted, of the lock boxes. “If you see them in your neighbourhood, don’t hesitate to report them.”

Lock boxes are an interesting proxy for the prevalence of Airbnb. Not everyone who has an Airbnb uses them, but they do make hosting a lot more convenient because your guest can get into the unit without you physically being there to hand off the keys. This would suggest—though I don’t have any data on it—that Airbnb hosts who use lock boxes are more likely to be frequent or seasoned hosts, and by extension exactly the type of host a city cracking down on Airbnb would want to target.

Lock boxes and smart locks turn out to be a robust discussion topic among Airbnb hosts, and also a niche market for locksmiths. For example, there is a $299 smart-lock on Amazon that advertises itself specifically as “Your Smart Lock for Airbnb.” Other smart-locks and lock boxes on Amazon describe themselves as the “Perfect solution storing keys for AirBnB rentals,” a “Preferred Partner with Airbnb,” and the “perfect choice for Airbnb rentals” (it only has one review on Amazon, but with a description like that, what could go wrong?). As for Montreal hosts looking to evade prying eyes, why not take a page from this host and install your lock box at the top of the door?

Elsewhere in Montreal, a man who was evicted from his apartment in December 2017 by a landlord who wanted to rent the units on Airbnb created a Facebook event for reporting illegal Airbnbs (it’s on Jan. 28, if you’re interested).

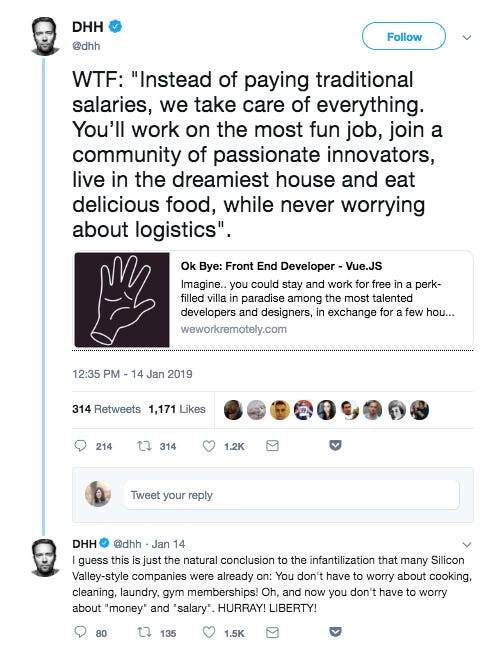

We Work Remotely.

I really have nothing to add to these tweets, so, shot:

This time last year.

Travis Kalanick tried to sell half his Uber shares, Handy pivots to retailers, “Shortcut Your Startup” (also I had the flu)

Other stuff.

I Am Ready for WeWork to Unleash My Superpower. WeWork and Softbank Live in Their Own World. Ford shut down Chariot because commuters didn’t want a better bus. Driverless car startup Aurora valued at over $2 billion. Driverless car startup Zoox gets new CEO. E-scooters test old traffic rules in Europe. Daimler drops platooning, focuses on automation. Airbnb host says unconstitutional for Nashville to block cancel her short-term rental permit. New York City alleges Manhattan brokers made $21 million off illegal Airbnbs. Bowery Valuation raises $12 million to automate real estate appraisals. Amazon to shutter Whole Foods 365 format. Amazon seeks leader for “perishable food platform.” Is Estrogen the Key to Understanding Women’s Mental Health? Sun exposure guidelines are unhealthy, unscientific, and quite possibly racist. A Silicon Valley Studio Apartment Is Being Rented to Two Cats.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and unleashed super powers to @alisongriswold on Twitter, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.