Travis Kalanick tried to sell half his Uber shares, Handy pivots to retailers, "Shortcut Your Startup"

LXXXIX

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy.

If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. This is issue eighty-nine, published January 9, 2018.

Selling out.

Remember how SoftBank's bid to buy a stake in Uber was so popular that shareholders had to pare back their offerings? Yes well that even happened to Travis Kalanick:

Former Uber Technologies Inc. Chief Executive Officer Travis Kalanick, who has long boasted that he’s never sold any shares in the company he co-founded, plans to sell about 29 percent of his stake in the ride-hailing company, people with knowledge of the matter said.

Kalanick stands to reap about $1.4 billion from the transaction with SoftBank Group Corp. and a consortium of investors who have agreed to buy equity valuing Uber at $48 billion, said the people, who asked not to be identified discussing private negotiations. Kalanick, who owns 10 percent of the company, had offered to sell as much as half of his stake -- the maximum board members were allowed to tender. He had to pare back the amount because of limits outlined in the agreement between Uber and the buyers, the people said.

The sale would make Kalanick, already one of the world's wealthiest individuals on paper, a billionaire in reality. When it comes to Uber, selling also seems to be the one thing that he and Benchmark agree on. The venture-capital firm, which famously sued Kalanick for control of the company over the summer, is reportedly cashing out 14.5% of its Uber holdings, worth about $900 million, in the SoftBank deal. Benchmark offered closer to 25% of its shares, but was limited by the tender offer being oversubscribed. Alphabet VC arm Google Ventures also sold about 14.5% of its shares, or $350 million worth; Menlo Ventures and First Round Capital sold even bigger chunks of their ownership.

These secondary sales to SoftBank were done at a $48 billion valuation, or a roughly 30% discount to Uber's previous valuation of nearly $70 billion. We talked before about why an Uber employee desperate for liquidity might jump at the opportunity to sell their shares, even at such a steep discount. But what about people like Kalanick, or firms like Benchmark, Google Ventures, Menlo, and First Round? Here is VC Fred Wilson on why those sales made sense, and the wisdom of taking money "off the table":

Taking money off the table is smart portfolio management. It is very different from selling your entire position, which could be brilliant but is equally likely to be a mistake. Selling a portion of your position, returning a multiple or two (or eight) of the fund, and holding on to the balance works out for you no matter which way the position goes in the future. If the position blows up, you got a lot out and booked a huge gain. If the position goes up significantly, you make even more money on the part of the investment you retained. If it goes sideway, you got a little bit out early. It is a win/win/win pretty much every way you look at it.

Also in Uber, Sprint CEO Marcelo Claure will join Uber's board as one of two SoftBank appointees. The second of those seats is going to Rajeev Misra, head of the SoftBank Vision Fund that led the multibillion-dollar deal to acquire a stake in Uber. The board will ultimately grow to 17 members or, as Kara Swisher puts it, "nearly two baseball teams."

Shortcut Your Startup.

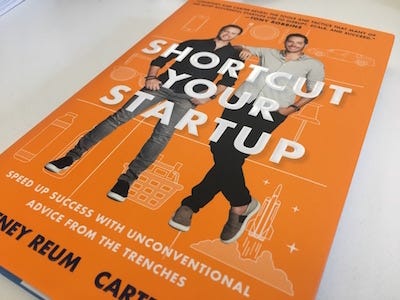

Startups often get in trouble for trying to cut corners to hack their way to success. We've seen this with Uber, with Hubble, with Zenefits, and with Theranos, to name a few recent example. The idea that success justifies unconventional tactics and demands breakneck growth is pervasive in Silicon Valley, and increasingly cemented in business books, like the one that arrived on my desk yesterday: Shortcut Your Startup: Speed Up Success With Unconventional Advice from the Trenches or, as I prefer to call it, What Could Go Wrong?

The book's bright orange cover features its authors, brothers and former Goldman Sachs investment bankers Courtney and Carter Reum, both striking unbearably bro-y poses. It presents its thesis on the first page of the introduction: "Today, the companies that win are those that move more quickly and flexibly than their competitors. This new environment requires new strategies, new mind-sets, and new tactics to shorten timelines, stand out, and win."

There is a certain tone that tends to define the self-help business book—direct, oversimplified, self-aggrandizing—and Shortcut Your Startup nails it. The Reums start by discussing the "just stupid enough" risk they took to leave Goldman and start their own company (VEEV, an açaí vodka alternative). They encourage budding entrepreneurs to "get into the trenches," including for team-building: "Cliché as it might sound, take your team to a Spartan Race or a Tough Mudder. These fun and increasingly popular obstacle course races are great entrepreneurial training grounds." They cite a lot of men who inspired them and who they think did things well and, 74 pages in, even introduce their idea of a successful woman! It's Jessica Alba, celebrity founder of The Honest Company, followed a few pages later by Tyra Banks.

The actual business advice includes: raise money and grow fast ("if you don't show fast growth, you're not going to capture the attention, dollars, and imagination of investors"), focus on "unfair advantages," and "don't expect your investors to read everything you send." In fundraising, they remind founders to, "as Carter likes to says [sic], 'ABC: Always Be Closing,'" which last time I checked was actually advice from Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross, but, you know, details.

The book is not good; I don't recommend you read it. The point is that by simply scanning Shortcut Your Startup, or any number of other startup how-to guides, it's easy to see where some of Silicon Valley's most toxic beliefs come from, and how they're perpetuated. There probably are people who will read this book and absorb not just its advice but also its implicit lessons: that startup culture is about taking the guys to tough mudders, that success is determined by finding and exploiting "unfair" advantages, that, so long as the company is growing fast, investors don't need to know what actually going on. What Could Go Wrong?

Technical skillz.

Gig economy startups that used to focus on consumers are increasingly catering to big businesses. Ikea bought TaskRabbit, Shipt sold to Target, Instacart is focused on building out its partnerships with established grocery chains. The latest is handyman and cleaning platform Handy, which has reportedly expanded its partnerships with retailers like Wayfair (online furniture) and Walmart.

Handy CEO Oisin Hanrahan says customers can't hang their own TVs or assemble their own bookcases because "people don't have these technical skills anymore… companies aren't teaching people how to repair machines or how to do technical work." That is a rather interesting definition of "technical skill," as most furniture assembly tends to involve matching up diagrams with the holes and screws that came with the pieces of your bookcase, rather than any particularly advanced knowledge of woodworking.

I'd guess the real issue is less about skills than growing income inequality. A certain class of people today have more disposable income than they used to, which means they have easier access to cheap labor. That's reinforced by the "gig" model, which outsources jobs and lets companies like Handy dictate rates, rather than the skilled professional, as well as the venture capital money that subsidizes prices, to make already labor appear even cheaper.

Elsewhere, in the-gig-economy-isn't-dead-yet, Nektyd is a new startup from two brothers in Colorado that connects skilled workers with people who need something done. It includes a rather confusing feature called "points of contact" that basically means "small business owner," since the so-called points of contact are "in charge of populating their links with people offering those services" in exchange for a cut of the fee. Nektyd, it turns out, is not pronounced "neck tied," but "neck tid," as in "connected" without the "co." It might help if Ryan and Steven Pfeifer 'necktyd with someone who could tell them they're a decade late to the party.

Ride-hailing vs. car-sharing.

Consulting firm AlixPartners is out with a new survey on "shared mobility," or, in this case, the adoption of ride-hailing and car-sharing. According to the survey of more than 5,000 consumers in seven countries (China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, the US), ride-hailing is better known and more popular than car-sharing everywhere but Germany and Japan. The report's authors think this preference is determined by "how strongly [ride-hailing] is regulated in each market," with rules being more stringent in Germany and Japan.

The services are also likely competitive: since AlixPartners last conducted this survey in 2013, car-sharing usage in the US has fallen from 15% to 8% of respondents, with the customer base of Zipcar falling from its 2016 peak. That makes sense if you assume that in the past people turned to car-sharing not just for vacation and day trips, but also for more routine needs, like to run errands or pick up a friend at the airport. Those needs are now just as easily serviced by an Uber or Lyft.

For both ride-hailing and car-sharing, price remains a key factor. Thirty-seven percent of people said they'd be more likely to use car-sharing if it were less expensive, and 35% said the same about ride-hailing. That's not a great sign for the Ubers and Lyfts, which are already heavily subsidizing their trips.

The second thing that people say would make them more likely to use ride-hailing is if it were "more price transparent." That's interesting because it suggests people not only think rides are too expensive, they're also frustrated with the sometimes wild variations in pricing. That could become a problem for a company like Uber, which is moving toward a system of dynamic pricing that charges people upfront based on what it thinks they're likely to pay.

Other stuff.

Lyft offering robo-taxis for CES. Aptiv, Lyft discuss partnership beyond CES rides. Free Lyft rides for musicians. Target will cut ties with Instacart after acquiring Shipt. Postmates driver spits on building security guard. Lyft Drivers Say They're Getting Shortchanged by the Company. Uber and Lyft drivers get lower DUI blood-alcohol limit in California. Uber restarts auto-rickshaw service in India. Why Uber Can Find You But 911 Can't. Judge tosses charges against Lyft, driver in girl's death. Uber partners with Nvidia on driverless tech. Toyota working with Uber on driverless shuttle service. Didi buys "significant majority" of Brazil's 99. Uber raises fares in Saudi Arabia. Uber rivals chase Europe. North Carolina attorney general plans to investigate Uber. Instacart teams up with Sprouts. Apple Pay promotes Instacart. Food delivery services a "prime culprit" for SF landfill. National Limousine Association runs ride-hailing attack ad with Pamela Anderson. The ethics of ordering Seamless in a snowstorm. New York man lists "snowfort penthouse" on Airbnb. "There remains something intensely personal about grocery shopping that delivery can't replicate."

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and startup shortcuts to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.