Political hardship.

New York City Council votes tomorrow on a package of bills that could cap the number of ride-hail vehicles in the city and set a wage floor for drivers. Uber has been running a political campaign in its app, with pop-up messages that update riders on the situation. “Experts agree: a cap on Uber won’t fix street congestion,” Uber was advising with one day to go, and, indeed, experts and editorial boards and even people who don’t really like Uber are in remarkable agreement that a flat cap is a bad idea.

Via is also running an in-app campaign, which warns that “city council wants to raise the cost of your Via” and provides a link to sign an email petition opposing a cap on vehicles. And then of course there is Lyft. Rather than target riders with a pop-up, the formerly pink mustachioed company (RIP) decided to do something a bit, er, bolder:

Facing a new regulatory crackdown that they say will severely impact their business, Uber and Lyft made an unusual proposal to New York City’s government: stand down, and in exchange we’ll bail out struggling yellow taxi drivers. The response was a polite no thanks.

The proposal — to create a $100 million “hardship fund” to support individual taxi medallion owners — was “summarily rejected” by the City Council and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s office, Joe Okpaku, Lyft’s vice president for public policy, told The Verge. “It’s a little bit astonishing to us.”

Of course, there were strings attached. The ride-sharing companies, including carpooling service Via, wanted the city to drop its proposals to cap the number of new Uber and Lyft vehicles and set a wage floor for drivers. In exchange, they said they would create this fund that they claim would pay out “tens of thousands of dollars” to individual medallion owners “right away.”

Allow me to translate: Lyft offered $100 million to struggling taxi medallion owners in exchange for not having to pay its own drivers a living wage.

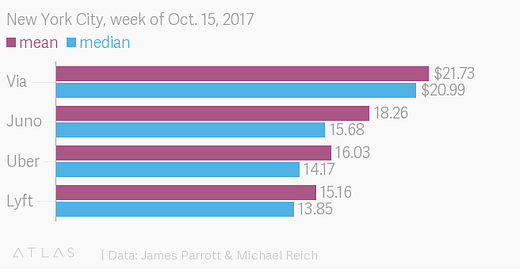

The bills that will almost certainly be adopted by city council tomorrow will allow the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC), the local taxi regulator, to set a wage floor of $17.22 an hour for ride-hail drivers based on the clever formula devised by economists James Parrott and Michael Reich. That will force almost every ride-hail company in New York to up its pay for drivers, and Lyft most of all. Because it was Lyft—not Uber—that Parrott and Reich found consistently paid its New York drivers the least:

Okpaku told the Verge that ride-hail companies would pay into the “hardship fund” at a rate of $20 million a year (i.e., he didn’t intend for Lyft to pay that $100 million by itself) and that it would be administered by philanthropic organization the Robin Hood Foundation. It’s unclear how the bill would have been broken up, but for ease of numbers let’s say Lyft offered to pay $50 million over five years. That would be a steal compared to the roughly $220 million more Lyft would have had to pay its own drivers over that same period under the TLC wage floor formula.

Considering this, it’s unclear why Lyft was so appalled by the city council’s rejection of its proposal that it felt the need to go running to the Verge, and describe it as “a little bit astonishing to us.” My only explanation is that Lyft is so convinced of its own moral righteousness that it’s unable to see when its ideas are clearly in the wrong.

Meanwhile, everyone else is trying to distance themselves from Lyft and its hardship politics. “Robin Hood is not a part of, and has not taken a position on, any of the proposed funds, or on the legislation pending before New York City Council on ride-share apps,” a spokesperson for the Robin Hood foundation told Politico yesterday. “We’ve never talked to the Robin Hood foundation about this and we aren't commenting on any private conversations we may have had with the Council,” Alix Anfang, an Uber spokeswoman, told Politico for the same story.

Airbnb advised.

Have you ever felt like the reviews on Airbnb were a little too good to be true? Maybe they actually were! I spoke to five Airbnb guests who say the company edited or removed their negative reviews of bad stays without their knowledge or permission.

Donna Oakley, a retiree in Fort Myers, Florida, (and mom of a former Quartz employee), said the company cut her 311-word review to a single sentence. Leslie McCree, a public health advisor in Atlanta, Georgia, wrote a review of a property in Sunnyvale, California, that initially didn’t post and then was later taken down for no apparent reason. Susan Rose, who I was sadly unable to fit into the story, found a pair of fuzzy pink handcuffs hanging on a wall of her Airbnb in Austin, Texas, a detail she included in her review and says Airbnb edited out. She also sent along a photo and honestly, can you imagine checking in and finding this:

Clearly there is some disconnect between Airbnb’s corporate PR and the people who are interacting with customers through its support line, because the exchanges these guests had with support made clear the customers were very upset to find their reviews had been removed or altered. And, I mean, wouldn’t you be too? If you went to the trouble of leaving a review in the good-faith interest of contributing to Airbnb’s open and accommodating community, wouldn’t you be a bit perturbed to find your comments weren’t showing up, or your carefully chosen words had been changed?

A related problem is that many “gig” economy companies struggle with ratings inflation, something we’ve discussed specifically in context of Uber. Since the story on Airbnb ratings ran, Tom Slee, who scrapes his own data on Airbnb, got in touch to say he’s noticed a decided increase in the average rating for properties on Airbnb. For example, here’s the trend he’s observed in ratings for listings in a number of US cities:

Feeling blue.

Had you forgotten about Blue Apron? Me too! They are still chugging along, though, now at about $2.15 a share. Second-quarter earnings were not good. Here is the Wall Street Journal, with the great headline, “Blue Apron Can’t Find Missing Ingredient”:

Getting perishable ingredients to customers has proven to be a logistical nightmare. On top of that, Blue Apron has struggled to retain customers. In the second quarter, net customers decreased 24% year over year to 717,000—below analysts’ expectations of 783,000.

And here is a chart from that same Journal story, with the equally great title, “Not Too Many Cooks”:

Bikes angels.

Bikes angels.

I highly recommend checking out this fascinating 10-minute documentary by Peter Gerard, “The Point of a Ride” (h/t Harry Campbell).

The mini-doc is ostensibly about “Bike Angels,” the program Citi Bike devised to encourage cyclists to help it with routine rebalancing—i.e., moving bikes to spots in the city where they are greatly needed. Bike Angels receive points in exchange for moving bikes; 80 qualifies for a free month of biking and each point beyond that earns you 10 cents. Gerard filmed the entire thing from a Citi Bike.But what the mini-doc is really about is the ultra-competitive people who aim to climb to the top of the Bike Angels leaderboard. “Psychosis of the Citi Bike Angel,” says one aspiring leaderboarder, which I think could also have been the film’s title.

It’s interesting to think about what Citi Bike has done here—essentially, turned one of its most important program maintenance tasks into a game. Compare this to what scooter companies are doing, paying contractors (read: anyone who feels like it) about $5 apiece to keep their scooters charged. “This is more fun than money-making,” Gerard told me. Who knows if fun works at scale, but it seems worth considering.

Elsewhere in bikes, Didi Chuxing and Ant Alibaba’s Ant Financial are considering a joint buyout of troubled bike-share startup Ofo. And over in Jackson, Wyoming, the town council has decided to buy six e-bikes.

Other stuff.

Gran raises $2 billion for super-app plans. “Uber for Poop” Aims to Break Up Senegal’s Toilet Cartel. Gig companies fight court ruling that could make their contractors employees. Spa-booking platform gets $5 million. RideOS raises $25 million to be traffic control for driverless cars. India’s Ola to launch in Britain this year. SoftBank leads $3 billion round into food delivery service Ele.me. Drive.ai begins driverless shuttle service in Frisco. Driverless scooters. Brandless gets $240 million from SoftBank’s Vision Fund. Kroger adds delivery. Amish Man Launches Horse-and-Buggy Ride-Sharing Service. Razor shared scooters launch in Long Beach. Bird expands to Paris. Good Job Portland, Only One E-Scooter Has Been Thrown in the Willamette River So Far. Bicycle graveyards. The Spy Who Drove Me. Who pays for roads? The great rental car debate. MoviePass Had Everything Going for It, Except Economics. “We’re on the internet, so we must be real.”