Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. Better late than never, hope you are all staying warm and coronavirus-free.

Thank you to everyone who sent in link formatting opinions. There was more enthusiasm for color-highlighted links but several of you said you found them distracting and noted that underlining is friendlier to people who are color-blind. In the interest of accessibility, I will stick with underlined links for now.

Food prep.

Coronavirus is making food delivery a viral hit as people bunker up and look to minimize human contact. Chinese food delivery firm Meituan in late January rolled out “contactless” delivery, an option to have the order dropped at a location requested by the customer to avoid any in-person meeting. Meituan’s contactless deliveries also came with physical cards for customers stating the temperatures of everyone involved in the cooking and delivery process, Business Insider reported.

Meituan has seen a surge in food orders for more than one person, as well as in grocery orders. The company reportedly has a shortage of grocery workers, and has had to borrow them from restaurants closed for the coronavirus outbreak. Meat, fruit, vegetables, masks, and sterilizers are all popular items. Quarantine cooking, anyone?

In the UK, where there are 115 known cases of the virus, British online grocer Ocado has warned of “exceptionally high demand” and advised customers to place their orders several days ahead. “More people than usual seem to be placing particularly large orders,” Ocado wrote in an email to customers. While Ocado didn’t explicitly connect the demand surge to coronavirus, hand sanitizer is almost entirely out of stock on its website. (“Bio-D Eco Lime & Aloe Vera Sanitising Hand Wash,” which contains no ethanol and retails for £4.20 per 500ml, remains available.)

Meanwhile in the US, grocers are trying to tamp down on ‘panic buying’ as shoppers empty shelves of hand sanitizer, face masks (stop buying these! They aren’t helping you, and there’s a global shortage for health care workers who actually need them!), bottled water (truly, I don’t get this one), and shelf-stable goods like fruit snacks, dried beans, and pretzels. Grocery delivery companies Instacart and Fresh Direct both say demand is high. The German word for panic-buying, by the way, is hamsterkauf, a portmanteau of hamstern (“hoarding,” from hamster) and kaufen (“buy”).

The flip side to this boom in business for on-demand companies is the precarity of their workforces. The people in the US who deliver groceries on Instacart, food on DoorDash and Grubhub, and goods on Amazon, are overwhelmingly hired as independent contractors, without employer-sponsored benefits like health care and paid sick leave. In an outbreak like coronavirus, that’s bad for a couple reasons.

The obvious problem is that these workers, who are often lower income, are less likely to stay home if they get sick or seek out proper medical care. This is a broad challenge in the US, where roughly 28 million people are uninsured, and one in four workers, or about 32 million people, have no paid sick time. Workers with no sick leave have little choice but to push through if ill, putting anyone around them—coworkers, commuters, customers, etc.—at risk. Researchers have in fact showed that cities that mandate paid sick leave have lower seasonal flu rates than those that don’t.

Another problem is that companies can only exert so much control over contractors, lest they be deemed employees. That means in a situation like coronavirus, the amount of guidance companies like DoorDash and Instacart can give on how their workers operate is limited. Yes, they can make recommendations (Lyft, for instance, has posted advice from the CDC and recommends disinfecting seat belts and car doors), but they’d be hard pressed to implement strict rules on sanitation, delivery, and everything else you might want a company to establish protocols on during an outbreak.

This is the paradox of gig work in the time of coronavirus. In theory, on-demand services are made for epidemics. It is arguably much better to have people who are or may be sick stay home and order things online than head to the grocery, restaurant, or corner store, where they risk infecting others. But the reality is much messier: workers on the front lines with no health benefits or sick time, companies unable to put in place the tight quality controls that would give you confidence their services are helping to contain the virus, rather than spread it. The US’s weak worker protections make it startlingly vulnerable to an epidemic. The gig economy is just one part of that.

The gig is up.

Speaking of employment classification, France’s top court affirmed that an Uber driver should be considered an employee, a decision that, you know, spells trouble for Uber and the broader gig economy in France. The Cour de Cassation upheld an appeals court ruling that the driver in question couldn’t be considered a self-employed contractor because he couldn’t build his own clientele or set prices, Reuters reported.

“When connecting to the Uber digital platform, a relationship of subordination is established between the driver and the company,” the court said in a statement. “Hence, the driver does not provide services as a self-employed person, but as an employee.” It doesn’t get much clearer than that! Uber, for its part, told Reuters the decision “does not reflect the reasons why drivers choose to use the Uber app,” which might be true but also seems beside the point.

The decision won’t automatically reclassify all Uber drivers in France to employees, but is another blow to Uber at a time when gig work is under siege from regulators around the world. San Diego, California, is inching closer to compelling Instacart to reclassify full-time shoppers as employees. The Ontario Labour Relations Board ruled couriers for food-delivery firm Foodora were dependent contractors, clearing their way to unionize. There is also, of course, California’s AB5 (Uber and Lyft are spending to unseat legislators) and the unresolved question of Uber drivers’ status in the UK, all of which adds up to one big regulatory headache.

Scooters!

Bird is charging different prices to some users in the same cities.

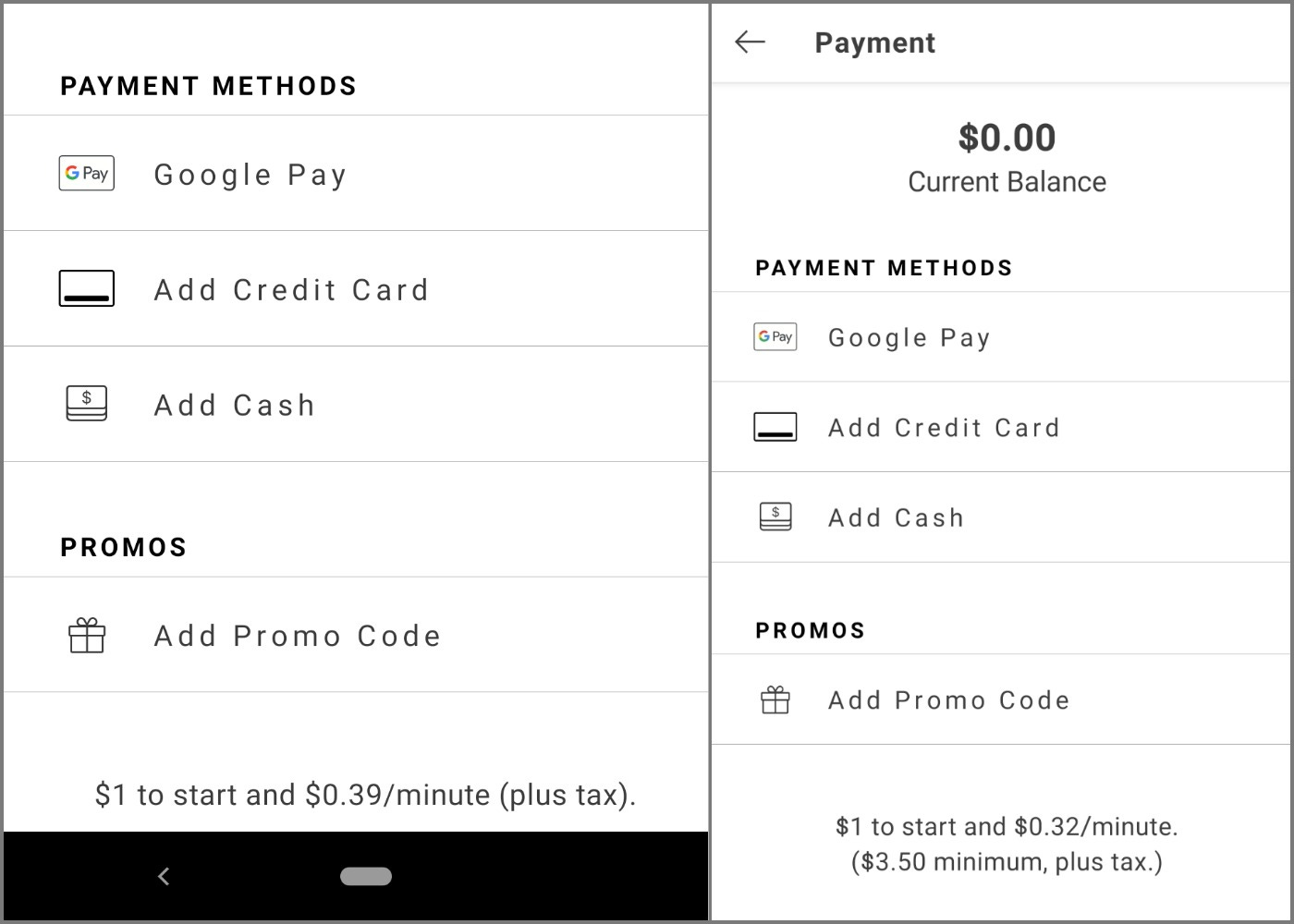

The discrepancy was spotted by Twitter user Asher, a good source on all things micromobility. He said Bird quoted him $0.32 a minute to ride a scooter, while a reporter in Atlanta was told $0.49 per minute. Curious! I asked a coworker who lives in Atlanta to check his Bird rates. Both he and his wife saw $0.39 a minute.

Left, my coworker; right Asher:

Bird’s prices aren’t the easiest to find. To access them, you open the Bird app, click on the menu button in the upper left corner, and then select “payment.” My Bird app, for instance, tells me it costs £1 to start and 25p per minute after that. (Electric scooters aren’t currently legal in the UK, so in my case this is pretty much a moot point.)

I reached out to friends and coworkers in a couple other cities, to see if they would also be shown different rates in their Bird apps. Here’s what they reported:

San Francisco/Oakland

$1 start + $0.32 a minute (three people)

$1 start + $0.29 a minute, $3 minimum + tax (one person)

Los Angeles

$1 start + $0.32 a minute, $3.50 minimum + tax (one person)

$1 start + $0.39 a minute, $3.50 minimum + tax (two people)

Washington, DC

$1 start + $0.39 a minute + tax (three people)

Bird described these variations to me as “entirely random pricing exploration in some of our markets and normal course of business” and said some individuals are “selected at random for short-term price experimentation.” That is all well and good but I can also promise you it will not mollify my Los Angeles coworker who was extremely displeased to learn he was being charged $0.39 a minute instead of $0.32. “JERKS,” he said.

🚨What rates is Bird charging you? I want to hear! Reply to this email, preferably with a screenshot 🚨

Bird, like a lot of other scooter startups, is still trying to figure out how to make its business work. It’s trying a bunch of stuff: subscription service, direct-to-consumer hardware sales, a seated moped/bike, in-app payments, and of course tweaks to pricing. Remember that when Bird initially launched, it charged $1 to unlock plus $0.15 per minute, with no trip minimum.

Shared scooters are a game of unit economics, which means pricing is key. As I’ve said before, one challenge scooter companies will likely run into is how high they can raise rental rates before customers decide they’re better off buying their own device. A standard 7-minute ride, for instance, would cost $3.73 plus tax (9.5%, in Los Angeles), or about $4.08 for a customer paying $0.39 per minute. Do just over 100 of those trips, or 50 roundtrip commutes, and you’d be better off buying this scooter on Amazon.

It’s also possible that Bird is betting a not-insignificant chunk of its users are fairly price insensitive, and might not notice if rates increased. In Los Angeles, for instance, quarterly surveys (pdf) by the Department of Transportation found that nearly half of dockless mobility riders earned more than $50,000 a year, and 23% made over $100,000. It’s certainly possible that some of those higher-income riders would be less likely to notice if scooter rates went up.

Another fun fact from those surveys: Asked how they would have commuted if an e-scooter or bike weren’t available, just 11% of respondents said they would have driven a personal car. Most people—48%—said they would have walked.

The rich.

They are not like us, they even do coronavirus differently!

Like everyone across the U.S., the rich are bracing for a deadly coronavirus outbreak. Ken Langone, the co-founder of Home Depot Inc., watched President Donald Trump’s press conference and wondered if the media was overplaying the risk -- but he also made two well-placed phone calls from his winter outpost in North Palm Beach.

One was to a top executive of NYU Langone Health, and the other was to a top scientist there. Both were reassuring.

“What I’ve been told by people who are smarter than me in disease is, ‘As of right now it’s a bad flu,’” said Langone, an 84-year-old who loves capitalism so much that he wrote a book called “I Love Capitalism!” He plans to come back to New York this month for an appointment. If he happens to feel sick, he will go to NYU Langone, and said he’d expect no special treatment.

Wellness guru Gwyneth Paltrow bought a designer face mask:

“En route to Paris,” Gwyneth Paltrow wrote on Instagram last week, beneath a shot of herself on an airplane heading to Paris Fashion Week and wearing a black face mask. “I’ve already been in this movie,” she added, referring to her role in the 2011 disease thriller “Contagion.” “Stay safe.”

Ms. Paltrow did not pose with just any mask, unlike, say, Kate Hudson and Bella Hadid, who also recently posted selfies wearing cheaper, disposable masks. The Goop founder and influencer of influencers instead opted for a sleek “urban air mask” by a Swedish company, Airinum, which features five layers of filtration and an “ultrasmooth and skin-friendly finish.”

What a time to be alive.

This time last year.

Shared scooters don’t last long

Other stuff.

Waymo raises $2.25 billion. Anthony Levandowski declares bankruptcy. Oyo cuts 3,000 in China. Latin American e-commerce company Peixe in talks to buy scooter firm Grow. Tier Mobility getting into mopeds. Uber’s path to profitability depends on Eats, Bernstein says. BlaBlaCar wants to be profitable again. E-bike startup Wheels lays off 6% of staff. Startups warn UK competition regulator could kill British tech scene. Yelp CEO asked to testify before Senate antitrust subcommittee. SoftBank’s Rajeev Misra Used Campaign of Sabotage to Hobble Internal Rivals. Improbable losses at SoftBank-backed Improbable World. SoftBank invests $100 million in employee-monitoring software. Office management company Eden buys Managed by Q for just $25 million. European Commission reaches data-sharing deal with Airbnb. Uber tests higher prices for trips starting in city centers. Delivery apps: still expensive. Coronavirus hits funding for Chinese startups. Profile of Tony Xu. Rebekah Neumann’s Search For Enlightenment Fueled WeWork’s Collapse.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and Bird rates to @alisongriswold, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.