Can the sharing economy survive this?

And what it means for this newsletter if its core beat goes up in smoke

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you!

A special welcome to all the new subscribers who found this newsletter via Twitter—which, at least as of now, is still standing—over the weekend. In light of so many new readers, and ahead of the Thanksgiving holiday in the U.S., I thought today was as good a time as any to pause and reflect on how things are going here at Oversharing HQ, aka my flat in London. (I sometimes get emails addressed to “the Oversharing team”; I regret to inform these readers that I am the entire team.)

What is Oversharing?

Oversharing is a smart and accessible guide to the gig economy, mobility, and sustainable urbanism. I started it in 2016 while working as a staff reporter at Quartz, as a home for stories about the sharing economy that I found fascinating but which, for one reason or another, weren’t a good fit for my day job. Oversharing was where I did my most voiciest writing and my wonkiest analysis; where I punctuated paragraphs with jokes and the occasional gif. I aimed to make Oversharing sharp but approachable; funny but thoughtful; opinionated but intellectually curious; the newsletter version of chatting with a witty friend at a cocktail party.

In the beginning, Oversharing grew slowly and mostly by word-of-mouth, aided by a supportive reader community. There wasn’t a growth target or master plan, but when sources began confiding that they liked Oversharing more than my work for Quartz, I figured I might be onto something.

After publishing 200 issues of Oversharing for free over four years, I transitioned to writing it full-time on Substack earlier this year. I now publish Oversharing 2-4 times per week, and have expanded the original scope from the gig/sharing economy to include micromobility, tech antitrust, and smart and sustainable urbanism. (The advantage of having a newsletter called Oversharing is that it can be about anything you want, really.)

It’s an experiment! And it depends on the support of readers like you. Like I said, I spent four years writing this newsletter for free in my limited spare time as a staff reporter and generally-busy-person-with-a-life. It was a lot of work and, in that classic paradox of scale, the more successful Oversharing got, the more unrealistic my continuing to do it for free became. I wanted Oversharing to remain accessible to the people who had read and encouraged it for so long, but I also knew all too well from working in media that high quality content can’t stay free forever.

So, that’s the deal. Since April, Oversharing has been a reader-supported publication, and its future as such depends on you. Becoming a paid subscriber supports and makes possible my work—the time I spend sifting through SEC filings, analyzing corporate financial data, updating and maintaining many spreadsheets and charts, reading books and research reports, chatting with sources, and of course writing and editing the final product, this newsletter.

Paid subscribers receive every post, have access to the full archive, can leave comments and participate in subscriber threads, and will soon be invited to occasional chat hangouts on the Substack app (more details tbd). A subscription usually costs $10/month or $100/year, but I’m running a 25% off HOLIDAZE promotion on annual memberships through the end of the year. If you enjoy and value Oversharing, consider subscribing.

Where do we go from here?

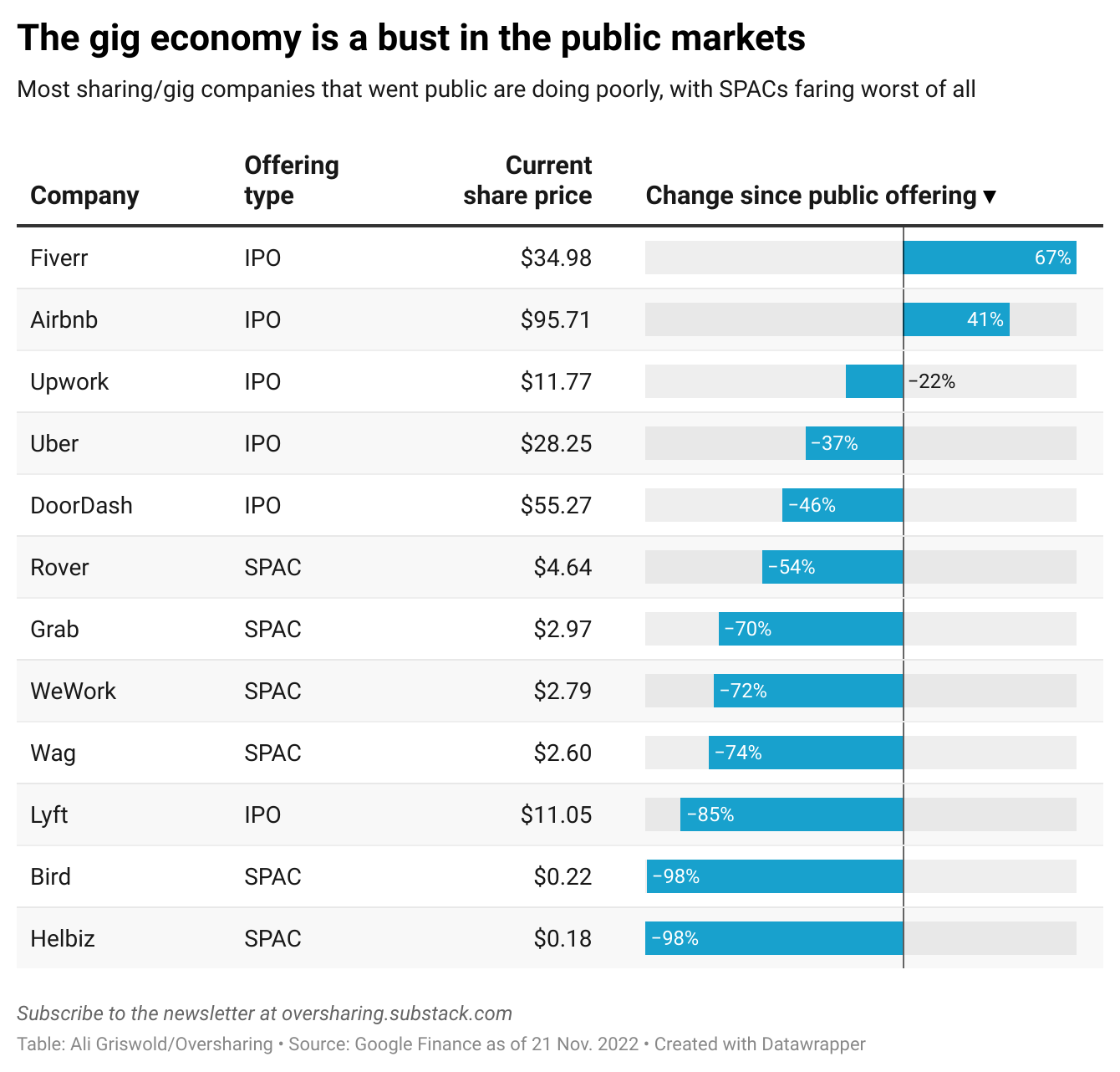

The other reason I want to pause and take stock is because we are at a very real inflection point for the companies that form the core interest of this newsletter. The gig economy is a bust in the public markets. That’s partly due to the broader tech selloff this year, and partly to gig and sharing companies finding public shareholders less forgiving than private investors of their chronic inability to turn a profit.

The collapse has been most acute for Bird and Helbiz, the two e-scooter firms that chose to go public via SPAC deals in 2021, thus allowing us to monitor their financial performance through the requisite SEC filings. I’ve been writing a lot about Bird lately, and my Twitter thread about the company’s myriad corporate woes (inflated revenue statements, a going concern warning) is what brought many of you here for the first time. If you’re just joining us, here are some past Oversharing issues on Bird you might want to check out (🔒 = paid subscriber post):

Bird founder Travis VanderZanden is selling his Miami mansion

🔒 Bird made better scooters. Now it needs people to actually ride them.

Over the weekend, I chatted with my friend and fellow Substacker Walt Hickey about the sharing economy outlook for his terrific newsletter,

. Numlock is the only daily newsletter I actually read because I always learn something that I wouldn’t come across in my normal headline scans, and also because Walt is hilarious. I joked that it feels like we’re living in the end times of my beat, as e-scooter firms implode, ‘instant’ delivery startups go bust, and publicly traded gig and sharing companies deflate. Walt asked to address that more seriously. What was happening at this moment? Was I genuinely worried about the fates of the companies that compose the Oversharing beat?The answer is yes and no. It seems clear that a lot of these companies won’t survive, as is always the case with startups. Things are looking grim for Bird and Helbiz, but also for the many firms that have yet to figure out how to make money after subsisting for years on venture capital subsidies and debt. Interest rates are rising; the free money is going away. That’s bad news for any company that hoped to coast indefinitely on borrowed funds and borrowed time until they figured out how to make their business model work.

Then there are other companies, like Uber and Airbnb, that I imagine will be fine because they really have achieved the scale they need to be ubiquitous. The reality of Uber is that even if it’s currently cheaper to take a taxi in a lot of cities—which it is!—people have gotten so used to taking an Uber and using ride-hail apps over the past 10 years that it’s hard to see a mass abandonment of that platform and a return to the old ways of hailing a cab. You could say the same of Airbnb, which changed how people live and travel by opening up new income to homeowners and creating a mass-market for ‘authentic’ experiences, and maybe for grocery and food delivery as well, especially in the post-covid era. Yes, there are lots of problems with these companies, from labor practices to lobbying and a history of regulatory abuse, but it’s hard to argue that their services have been transformative.

That doesn’t mean that Uber will always look like it is now, but if I had to bet, I’d guess it and a handful of others will stick around. I had an interesting conversation over the summer with economist Marshall Steinbaum, who alluded to companies like Uber being in a “recoupment phase” after years of subsidizing their services. Recoupment is the phase in which a company has become such a dominant competitor that it’s able to use its monopoly-esque scale to raise prices and claw back earlier losses. We saw Amazon do this, and we may be witnessing Uber and a handful of others doing it now. But that’s a topic for another Oversharing, which I very much hope you’ll come back for.

I Feel Your Pain (grin).

1. Re The "Sharing" Economy: we already had one (rental cars, rental apartments), then SV and IT and VC arrived and we got more. Looking only at transport, since I know zilch otherwise, Uber et al. proved that if you spent maybe $75 billion you could create international cab companies that might be able to break even (and do better in places where private ownership is more constrained, e.g. Beijing). Then along the way they picked up food delivery, and THAT looks like it might be feasible.

2. Re "Oversharing:" time to pivot! (I can't believe I used that word!) The "Sharing Economy" despite all its foibles launched the micromobility boom, starting with shared scooters. As the rose came off eternal rental ("If I like scooters so much, why don't I just buy one?"), the micromobility wave still rolled on, just now more owned than rented. E-bikes, delivery bikes, quadra-everything, min-EVs, etc. Here I bet the next struggle will not be Shared/Owned but The Mode Wars. Types of micromobility modes are proliferating rapidly. Is a 4-wheeled micro-car a bike, a motorcyle, or a car? How to regulate? How to avoid micromobility ballooning into macromobility? ("If I had just 10 more HP and could seat 3 instead of 2..."). IMHO.