What to do about accidental surge?

The problem with real-time pricing is that it happens in real time

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

Oversharing is now a subscriber-supported newsletter. Paid subscribers get three posts per week with the most in-depth analyses of the gig economy, mobility, and urban life; full access to the archive; and exclusive access to comments and community threads. Subscribe now for a special launch period rate of $7/month or $70/year.

Surge.

Uber and Lyft landed in hot water for charging surge prices to some Brooklyn riders after last week’s horrific subway attack in Sunset Park. Angry customers shared screenshots on Twitter showing ride-hail fares of $68 to $85 to get a car near Sunset Park in the aftermath of the attack. Lyft later said it suspended its version of surge pricing, Prime Time, citywide the day of the shooting while Uber said it disabled surge pricing in the ‘vicinity’ and capped prices throughout the city. Both companies said they would refund riders who paid elevated prices during the incident.

Accidental surge is a problem ride-hail firms have yet to solve. By accidental I mean surge pricing triggered the normal way—by sudden increases in demand in a particular area—but in response to an incident or emergency like the subway attack that makes it callous and inappropriate to charge higher prices. This has happened a couple times before, for instance, after a hostage situation in Sydney in 2014 and following an explosion in Manhattan in 2016. Of course, the most famous surge incident came not over accidental surge but when Uber disabled high prices during a taxi drivers’ strike against Trump at JFK airport in 2017. Uber turned off surge to prevent prices from spiking over the protest, lack of taxis, and reduced transit service, but the move was misinterpreted as an attempt to strike break, launching the viral #DeleteUber and inspiring some 500,000 people to delete their Uber accounts. Five years later that story is still so crazy. I mean, half a million people deleted their Uber accounts over what was effectively fake news!

Anyway. What to do about accidental surge? The problem with real-time pricing is that it happens in real time. The surge algorithm senses a shock to the demand curve and it responds by raising prices. The trouble is that, as far as I’m aware, these algorithms are not particularly discerning about the cause of a demand shock. And so a surge triggered by a concert letting out at Madison Square Garden starts to look very similar to one caused by an attack on a subway station in Brooklyn on a Tuesday morning. This might not be the best example: you would hope a company as technologically sophisticated as Uber would be aware of events like concerts and able to distinguish between ‘expected’ surges and anomalous ones, like after the subway attack. My point is simply that from the perspective of a pricing algorithm, a change in demand is a change in demand regardless of the cause.

The other thing worth noting about last week’s accidental surge incident is that Uber and Lyft no longer tell riders how much prices have increased by, only that fares “are slightly higher due to increased demand,” as Uber puts it. So, the riders who tweeted those screenshots knew prices were higher than usual, but they didn’t know how much higher. Uber made this shift years ago when it stopped showing riders a surge multiplier and instead simply quoted a fare at the time of the ride request. Prices still varied with demand, but riders no longer knew how much more than normal they were paying. Uber calls this “upfront pricing” and claims it provides “more clarity for riders” as they agree to the fare when they book, avoiding surprises later on. Whether you also see it this way I suppose depends on your definition of clarity. With upfront prices, you know what you’re paying when you make the purchase, but you don’t know why or have any assurance you’ll pay the same price another time. It’s like if your local cafe didn’t list any prices and sometimes your latte was $2.85 and other times the barista was like “hi there, that will be $3.57 today due to slightly increased demand, would you still like to order?”

The more pertinent comparison is between ‘upfront’ prices and the traditional taxi meter. With the taxi meter, you don’t know at the outset what the final price of your ride will be, but you know exactly why you’re being charged the way you are. Usually you pay a base price for starting the ride and then per minute and per mile after that. The fare can vary based on things that affect time and distance, like traffic or the route your driver takes, but how you arrive at that final fare is very straightforward. Upfront ride-hail fares are the opposite. You know the price at the outset, but you have little to no information that might help you understand if the price you’re paying is typical. A lot of people prefer this! It can be anxiety-inducing to try to estimate your fare or watch a meter tick up from the back seat, and upfront pricing solves that. But it also makes it harder to get a sense of the relative cost of a ride service in the way you know what your regular coffee costs, or that a box of pasta should be about $1 and anything more is a premium. All of which makes surge harder to notice in general, except in extreme circumstances.

Waste less.

‘Instant’ grocery delivery startups like Getir abandoned the assetless model of the Uber era in favor of delivering from small warehouses or customer-free ‘dark stores’ that they manage themselves. The dark-store model is probably faster than having gig workers pick items from the shelves of regular consumer stores, the way an Uber Eats or Instacart does, which is essential to hitting those 15-minute delivery targets. But it also means these companies have to manage their inventory and deal with spoilage and food waste.

So far that hasn’t gone great: recently shuttered Buyk was spotted throwing out garbage bags of groceries in Chicago and Gopuff reportedly mismanaged supply so badly that it routinely left entire pallets of food to spoil (“unfortunate but at times inevitable within the grocery and food industries,” a spokesperson told Business Insider). But they’re working on it. Getir recently partnered with Copia, a tech startup working to reduce food waste, to deliver surplus groceries from its stores to nonprofits in New York City, Chicago, and Boston. Farmstead, another online grocer that uses a dark-store model, last week debuted an ‘Eat this First’ section on its email receipts advising customers what products they should consume first to reduce food waste.

Food waste is a massive problem, especially in the U.S., where it’s estimated at 30-40% of the food supply. Instant and online grocery is a small part of this, but every little bit helps. The email receipt advice, for instance, seems like an easy and obvious step. In the UK, online grocer Ocado already does this: order receipts are broken out by ‘fridge’ and ‘cupboard,’ and items within those sections labeled with their use-by dates (for instance, ‘use by end of Sunday’ and ‘products with a use-by date over one week). It’s a clever design choice and, from personal experience, it also works: Ocado’s receipts nudge me to put items with earlier use-by dates at the front of my fridge, meaning I’m more likely to eat them before they go bad. It would be nice to see more online grocers making choices like that.

Hotels first.

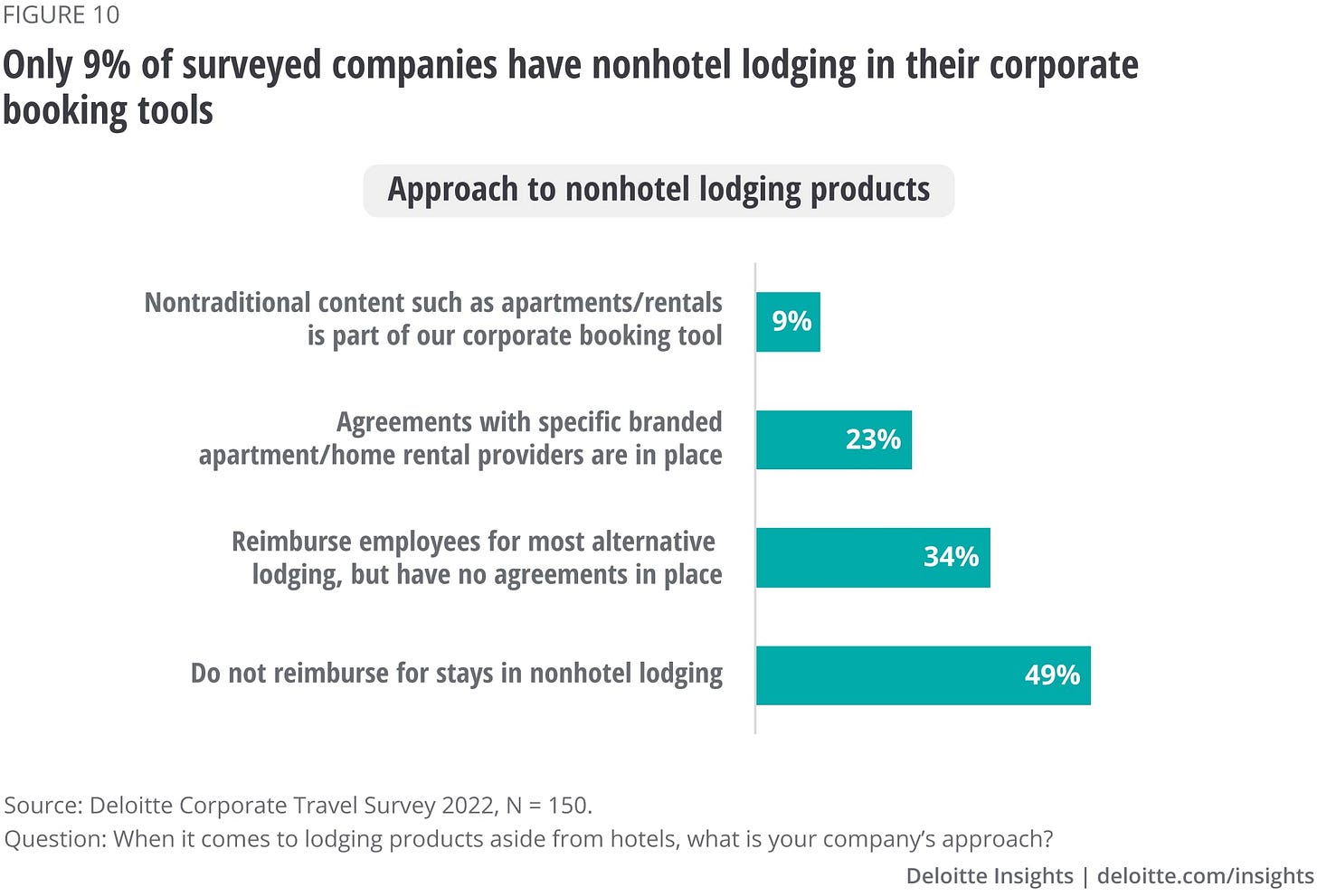

Companies still prefer traditional hotels to alternative rentals like Airbnb for business travel, according to a new report from Deloitte. Only 9% of companies surveyed said they include home-rental options in their corporate booking tool, while half said they don’t reimburse for stays in nonhotel accommodations.

Airbnb rebounded in 2021, even recording a $55 million profit in the fourth quarter, but CEO Brian Chesky noted on the company’s earnings call in February that one-night stays—presumably business travel, he said—was the only category not to improve from before the pandemic. “I don’t think that business travel is ever going to come back the way it was before the pandemic,” Chesky told investors. “It doesn't mean business travel is not going to come back. I just think it's going to be different because the way we work is different.”

Other stuff.

Uber suspends service in Tanzania, citing tough regulations. Two dead in mass shooting at party held in Pittsburgh Airbnb rental. Bill to loosen Airbnb regulations in Nashville defeated in House committee. Uber Eats to offer online payments with Rakuten Pay in Japan. Gopuff taps former Amazon executive to oversee North American business. Two SoftBank LatAm partners leave to start own firm. Grocery chain Wegmans ditching single-use plastic bags. Tokyo-based micromobility startup Luup raises $8 million. Egyptian cloud kitchen startup The Food Lab raises $4.5 million. Restaurant management startup UrbanPiper raises $24 million from food delivery rivals, others. Bike taxi startup Rapido raises $180 million led by delivery platform Swiggy. L.A.’s injury rate from e-scooters may exceed national rates for motorcycles, bicycles, and cars. The best affordable electric bikes, per Electrek. Redditor makes super-detailed map of NYC bike lanes. Are 1,818 Airbnbs Too Many in Joshua Tree? Toddler accidentally orders $100 of Starbucks on Uber Eats, leaves $32 tip. How Japan Built Cities Where You Could Send Your Toddler on an Errand.