Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy.

If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. This is issue ninety-seven, published March 6, 2018. Programming note: Oversharing is taking a break for the next few weeks while I am Off The Grid for vacation. It will resume in April.

What happened.

Some time last month, MIT published a two-page research brief of a forthcoming paper, "The Economics of Ride-Hailing: Driver Revenue, Expenses and Taxes." The brief explained that through a "detailed analysis" of survey data, the authors, all Stanford affiliates, had found that the median profit from driving for Uber or Lyft was $3.37 an hour before taxes—well under minimum wage. The brief flew under the radar until last week, when PR firm Berlin Rosen sent a March 1 email blast about its "bombshell findings." The internet was soon flooded with headlines like:

Uber, Lyft Drivers Earning A Median Profit Of $3.37 Per Hour, Study Says

After Costs, Uber and Lyft Drivers Average Less Than $4 an Hour, Depressing New Study Claims

Uber, Lyft drivers actually earn less than minimum wage, MIT survey suggests

MIT study shows driving for Uber or Lyft is worse than literally any real job

Uber-affiliated economists rushed to Uber's defense:

As did Uber CEO Travis—I mean, er, Dara Khosrowshahi:

So what happened? The MIT study was based on self-reported earnings data from a survey of about 1,100 Uber and Lyft drivers conducted in 2017 by Harry Campbell at driver blog The Rideshare Guy. The authors made a series of adjustments to the results. Most importantly, they took the response to survey question 14, "how much money do you make in the average month," and discounted it based on the response to survey question 15, "how much of your total monthly income comes from driving." For example, if someone answered "$1,000 to $2,000" to question 14 and "around half" to question 15, then the authors decided that person made about $1,400 a month (a statistical assumption) and around $700 from driving.

The problem with this methodology is that it is unclear from the survey whether drivers responding to question 14 were reporting their total monthly income from gig/on-demand work, or from everything, including part- or full-time jobs they might have. The question itself is unclear: "How much money do you make in the average month? * Combine the income from all your on-demand activities." It is easy to see how one person might interpret that as, "how much money do you make from on-demand work in the average month" and another as "how much do you earn total in the average month, including but not limited to all on-demand activities." Assuming that even some drivers interpreted the question the first way, discounting becomes unnecessary and problematic.

This is all explained in a critique of the MIT paper that Jonathan Hall, Uber's chief economist, posted to Uber's blog on March 2. Hall's commentary noted that the MIT findings differed "markedly" from previous studies on driver earnings. A study Uber conducted with Princeton's Alan Krueger estimated hourly net earnings (after Uber's fees but before expenses like gas and vehicle depreciation) at $19.04 in October 2015; a study Uber did with Stanford professors estimated gross hourly earnings (before all fees) at $21.07 from January 2015 to March 2017; and Campbell's own analysis of his survey put net earnings at $15.68 per hour. MIT's researchers have agreed to revisit their findings.

I read the full MIT study and it doesn't take a degree in advanced mathematics to tell that something is off. The conclusions are grossly out of line enough to signal a possible error, and the full list of survey questions, included as an appendix to the paper, reveals multiple questions that could have been confusing and elicited inconsistent responses from respondents. That said, the study was attempted for good reason. "Estimating the economics of ride-hail driving at a large scale presents a number of challenges," the authors write in their introduction. "An individual driver can precisely observe his or her own operational costs, but does not know whether those costs are representative of other drivers or vehicles. Researchers and policymakers are at a further disadvantage since they neither know specific revenues nor do they know the year, make and model of vehicles driven to make informed estimates of costs.

We have talked before about how little good data there is on the gig economy, and most of what we know about Uber driver earnings comes from Uber. This is unfortunate because Uber doesn't have a great reputation for being honest with its data. Uber famously said New York drivers earned a median income of $90,000 a year (they didn't). It later settled with the FTC for greatly exaggerating how much drivers could actually make. Uber is constantly fiddling with how drivers are paid, most recently dropping its commission structure for a new system that pays drivers on more of a metered basis. A lot of the money drivers earn also isn't even based on fares—it's tied up in "boosts" and "quests" and other gamified incentives Uber uses to nudge drivers into working particular times and places. Most of Uber's in-house academic research on driver earnings is by now outdated. Papers like Krueger's also tend to highlight the net hourly earnings of drivers, an academic sleight-of-hand that inflates the numbers we hear talked about for "what Uber drivers actually make" by omitting very real on-the-job expenses like gas, insurance, and vehicle depreciation.

This context is crucial because it means that when Uber says drivers make X, very few people trust it. Drivers don't, the FTC didn't, and a lot of the public probably doesn't either. The flip side of that is that when seemingly reputable researchers from places like MIT and Stanford come along saying, we did this analysis, and our calculations show Uber drivers earn less than the minimum wage, a lot of people are ready to believe them! The cost of a bad reputation is the benefit of the doubt. We saw the same thing happen last year, when half a million people deleted their Uber accounts over a "strike" the company was said to break up but actually had nothing to do with. Sure, $3.37 an hour was a crazy number. But when people are primed to believe that Uber lies and driving for Uber is a crappy job, then you better bet they are going to believe a prestigious academic study that comes along telling them exactly that.

Hatching Silicon Valley.

The chicken (or the egg?) is the latest status symbol in Silicon Valley:

In true Silicon Valley fashion, chicken owners approach their birds as any savvy venture capitalist might: By throwing lots of money at a promising flock (spending as much as $20,000 for high-tech coops). By charting their productivity (number and color of eggs). And by finding new ways to optimize their birds’ happiness — as well as their own.

Like any successful start-up, broods aren’t built so much as reverse engineered. Decisions about breed selection are resolved by using engineering matrices and spreadsheets that capture “YoY growth.” Some chicken owners talk about their increasingly extravagant birds like software updates, referring to them as “Gen 1,” “Gen 2,” “Gen 3” and so on. They keep the chicken brokers of the region busy finding ever more novel birds.

The entire story is delightful and you should go to the Washington Post to read it. Venture capitalists and other rich tech types are reportedly spending tens of thousands of dollars on chickens that produce rare and colorful eggs, which they then bring to their friends at parties:

There was a time, not long ago, when Matt Van Horn and his wife, Lauren, would arrive at a dinner party with a nice bottle of wine in hand — usually a zinfandel from their favorite vineyard in nearby Napa.

But lately the Van Horns are more likely to offer something they consider more impressive. They come bearing a six-pack — of eggs.

Not just any eggs, but a handpicked, coffee-colored collection laid by Queen Elizabeth, Bear or one of the Van Horns’ other heritage breed chickens, inhabitants of a cozy coop on the family’s backyard deck overlooking Sutro Forest. As a final touch, each carton is stamped with the family’s specially designed seal of approval: “VH SF Eggs.”

Watch out, Whole Foods.

SLOG 2.0.

Once upon a time, before Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber liked to mess with its competitors in obviously shady ways. In 2013 and 2014, both Lyft and Gett alleged that some number of Uber employees (Lyft said hundreds, Gett dozens) were booking and then just as quickly cancelling thousands of rides to tie up their platforms. The idea was that drivers would be dispatched to those trips, taking them out of the available driver pool, only to have the rider cancel at the last minute. It later came out that Uber had a name for the strategy—Operation SLOG—in which it armed contractors with burner phones and credit cards in an effort to undermine Lyft and Gett. Uber attempted to spin this as a "marketing" tactic to recruit new drivers, and reminded SLOG contractors that talking to the press violated their non-disclosure agreement.

Anyway here is a story about Lyft:

SYRACUSE, N.Y. -- Lyft has given one of its drivers here a phone and a line of credit and sent him to out to hail Uber drivers throughout Syracuse.

His job? Recruit drivers to Lyft and conduct "competitive research" on Uber, Lyft officials confirmed.

It's one more sign of the intense competition between Lyft and Uber, two ride-booking apps. Another sign is that Lyft has begun an ad campaign to recruit more drivers here, offering up to a $350 signup bonus.

Unlike most of the US, upstate New York only recently began allowing ride-hailing, meaning the market is still in its early stages. The Lyft spokeswoman, who declined to give a name, said this "recruiter" is supposed to hail rides from random points in Syracuse and ask drivers about Uber's business model. The recruiter earns a commission for convincing Uber drivers to sign up for Lyft. The Lyft spokeswoman "denied the recruiter is using any shady tactics such as hailing rides and cancelling them, or leaving bad reviews."

Moving on, here is a story about OpenTable:

OpenTable, the market leader in the online restaurant-booking world, is embroiled in a scheme that affected 45 Chicago restaurants that use Reserve, an OpenTable rival. Last week, OpenTable confirmed they fired an employee who made several hundred reservations at restaurants using Reserve, which resulted in hundreds of no-shows over the course of the past three months. Reserve and several Chicago restaurant workers allege that the employee, who remains unnamed, wanted to convince those Reserve customers that OpenTable was a better product and intended to use the no-shows in their sales pitches.

“This was obviously done with the intent to harm Reserve,” said Reserve COO Michael Wesner.

One thing that's funny about tech companies is they spend all this time "innovating" and "disrupting" and then they go around all doing the same thing! You'd think they would come up with more ingenuous methods of competitor sabotage, but no. Uber did a lot of bad stuff and I am not endorsing any of it (Greyball, Hell, paying off hackers, etc.), but at least it had a little creativity.

Staying alive.

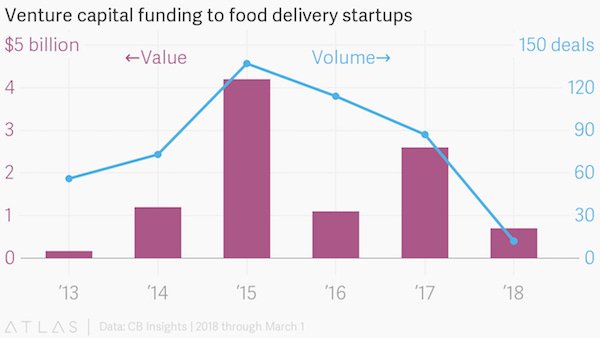

Food delivery isn't dead yet. San Francisco-based DoorDash has raised $535 million from SoftBank and other investors at a $1.4 billion valuation. That brings funding to food delivery startups to $702 million so far in 2018, two-thirds of what was raised during all of 2016, and ahead of the pace at this point in 2017.

Food delivery startups that have closed their doors include Maple, Sprig, and SpoonRocket. More consolidation is likely, as rich investors like SoftBank concentrate their bets on established companies like DoorDash. The SoftBank investment is interesting because DoorDash is a competitor of UberEats, which SoftBank is also invested in via its multibillion-dollar stake in Uber. But, you know, conflicts haven't stopped SoftBank before.

Other stuff.

Lyft partners with Seated on restaurant reservations. Ford tests self-driving delivery with Domino's and Postmates in Miami. Lyft's Logan Green and John Zimmer carpool to work. Uber co-founder Garrett Camp starts his own cryptocurrency. Roommate finder Roomi acquires competing app Symbi. RedDoorz raises $11 million for budget hotels. Daimler buys out rest of Car2Go. John Legend, Chrissy Teigen visited by cops in alleged illegal short-term rental. Uber launched Uber Health to transport patients. Lyft expands partnerships with healthcare providers. Uber sued for discriminating against people in wheelchairs. Brazil backs looser rules for Uber. Chinese used-car seller Chehaoduo raises $818 million. Alibaba invests $150 million in India's Zomato food delivery service. The New Economy Working Group. Dorm life in San Francisco. Industrious raises $80 million. Illegal tents on Airbnb in NYC. Uber rider who blacked out charged $1,600 fare. Woman says raped twice trying to take a Lyft home. Uber but for back office finance guys. Bikes everywhere!

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and dubious econ papers to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.