Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

I’m in Seattle this week and San Francisco the next. Get in touch on Twitter (DMs are open) or by replying to this email if you’re interested in meeting up.

I regret to say Quartz was narrowly defeated by Tourmaline in the quarter finals of the 2018 Mineral Cup. Now throwing my lot in with Ice.

Safety first.

In June, one of Waymo’s self-driving Chrysler Pacifica minivans crashed on the freeway outside of the company’s office in Mountain View, California, after its lone safety driver fell asleep at the wheel, The Information reports:

Behind the wheel of the Pacifica was a human driver who, after about an hour on the road, appeared to doze off during the drive, according to a person who has seen a video of the incident and another person who was briefed about it. In doing so, the driver inadvertently turned off the self-driving car software by touching the gas pedal, and then failed to take over the wheel, another person familiar with the matter said. The van crashed into the highway median.

The driver who dozed off didn’t respond to any of the vehicle’s warnings, including a bell signaling the car was in manual mode and another audio alert. He reportedly woke up once the car hit the median, then turned around and headed back to the Mountain View office. He no longer works for Waymo.

Waymo got lucky with the accident. The safety driver wasn’t hurt and no other vehicles were involved. Waymo reported the vehicle sustained “moderate damage to its tire and bumper.” The company said in a statement that it is “constantly improving our best practices, including those for driver attentiveness, because the safe and responsible testing of our technology is integral to everything we do.”

Improvements in this case meant altering night shift protocol to have two safety drivers instead of one, to guard against someone nodding off at the wheel. At a company meeting to discuss the incident, one attendee reportedly asked whether safety drivers were on the road too long, and was told that drivers can take a break whenever they need to.

Waymo is pursuing fully self-driving software that wouldn’t require any intervention from humans, in contrast to automakers like Tesla and General Motors that have started with selectively automated features to assist human drivers. As Waymo has gotten closer to true autonomy, it’s also tried to reduce its reliance on human safety drivers, for example, by cutting the number of safety drivers in a test vehicle to one from two. Waymo plans to launch a commercial ride-hail service with driverless cars in the Phoenix area this year.

After a self-driving Uber struck and killed a pedestrian in Tempe, Arizona, in March, one point of focus was on Uber’s safety driver policies. Jalopnik pointed out that “almost everyone”—Toyota, Nissan, Ford’s Argo AI—used two people to test self-driving cars. Rafaela Vasquez, on the other hand, was a lone safety driver at night in the Uber Volvo that crashed. She was later found by police to be streaming “The Voice” on her phone at the time of impact.

One thing everyone working on driverless cars agrees on is that humans are bad drivers. People from Waymo CEO John Krafcik to disgraced former Uber engineer Anthony Levandowski—and I challenge you to find a more diametrically opposed pair—like to talk about how driverless cars will save lives by eliminating thousands of preventable highway fatalities a year.

It is baffling, then, that these companies trust the very humans they seek to unseat to watch over their adolescent technology, alone and for hours on end. An autonomous safety driver once described to me working 10- to 11-hour shifts unaccompanied, including nights that began in the early evening and ended well past midnight. Drivers could take breaks whenever they wanted, this person said, but it was still a challenge to stay focused for that long without anyone to talk to, or much to do beyond watching the road.

A few months after the Tempe accident, Uber laid off most of its self-driving car operators in Pittsburgh and San Francisco. Uber said it would replace these people with “mission specialists” trained to monitor its cars on roads and on specialized test tracks. These mission specialists are supposed to be more involved in the actual development of the cars, tasked with tracking, documenting, and triaging any issues that might crop up. Per a current job listing, they should have “the ability to operate independently with little or no supervision.”

I often come back to this essay by Tim Harford about how our quest to automate all things may be setting us up for disaster. The more we let computers fly planes, drive cars, operate machinery, and so on, the less time the people we’ve put in place for backup—the pilots and safety drivers and other operators—are able to practice their skills, and the greater the odds they’ll be unprepared in a true emergency. This problem is known as the paradox of automation, and it applies to benign problems as well, like how we struggle to remember phone numbers that are stored in our mobile devices, or to do mental math that we can punch into a calculator. Like any skill, these need to be practiced to be maintained, and become rusty with disuse. Instead of designing technology for humans to babysit, Harford wonders, why aren’t we making technology that babysits humans?

Ditch your car.

Also in The Information, Lyft more than doubled revenue to $909 million in the first half of 2018, compared to the same period a year earlier. The company’s net loss grew to $373 million, but at a slower rate from the previous year, due to better control of expenses like rider promotions. Here’s a bit more on what that means, per The Information:

In other words, Lyft lost 41 cents for every dollar of revenue it generated in the first half. While that’s a lot of red ink, it’s a marked improvement on the first half of 2017, when Lyft lost 62 cents for every dollar of revenue it reported. Lyft has to continue pushing down the net loss as it grows if it is to get a good reception from investors when it goes public, which is expected to happen next year before Uber goes public, as The Information previously reported.

The driving theme is that Lyft is cutting costs by becoming more efficient. The company has improved its gross profit—the amount left after deducting credit card fees, insurance costs, and technical infrastructure maintenance from its revenue. Lyft is also spending less, percentage-wise, on sales and marketing, which includes things like discounts for riders and bonuses for drivers. This is how it’s supposed to work: the company grows and matures, and then uses this growth and scale to streamline operations, refine its model, and eliminate inefficiencies, preparing it to eventually go public. But lots of privately held technology companies don’t do this anymore. Instead, they bank on venture capitalists and deep-pocketed investors like SoftBank to bail them out when they run low on cash, avoiding the scrutiny of investors in the public market.

Elsewhere in Lyft, the company expanded its ditch-your-car challenge to 35 cities, including Boston, New York, San Francisco, and Washington DC. The first challenge invited 100 people in Chicago to give up their personal vehicles for a month in exchange for $550 in credit toward Lyft, bike-share, car-share, and public transit. The Verge reports that one participant in the Chicago program said it inspired him to sell his car.

Unfortunately if you were interested in signing up, Lyft says it’s no longer taking entries. The company only took 50 participants per city this time around (except in Los Angeles, where it took 100) and offered, generally, $300 in Lyft credit, a monthlong Zipcar membership with $100 in credit, a monthlong pass on local public transit, and sometimes a month of access to a local bike-sharing service. One exception is New York, where Lyft inexplicably didn’t include a monthly subway card in the package, which is the main thing that most New Yorkers use to get around, and would go a lot further toward Lyft’s ostensible goal of getting people out of cars than $300 of Lyft credits. You can check out the full details and city list here. Anyway, I can see why the challenge filled up quickly since this seems like a good deal! Though admittedly I say that as someone who doesn’t have a car to give up in the first place.

Unexpected party.

When you do anything as frequently as Uber does rides, weird stuff is bound to happen. For example, take the case of Yeimy, a married woman in Colombia, who was caught having an affair when her Uber driver turned out to be her husband.

Yeimy and her lover, Jesús, met up in Santa Maria and ordered an Uber to a motel. The Uber app assigned her a driver named Leonardo, but who was actually her husband driving under a friend’s vehicle and Uber account. (Note: driving under someone else’s account violates Uber’s driver policies.) Yeimy and her husband reportedly recognized each other once she and Jesús got into the car.

This wasn’t the first time someone was caught, er, oversharing while ridesharing. Last year, a female Uber driver picked up a rider at the airport whose destination was the apartment complex the driver’s boyfriend lived in. It seemed like a coincidence, until they pulled up to the apartment and the boyfriend—who had claimed to be out of town visiting his mom in the hospital—came out of his apartment to greet the other woman and help with her luggage.

The fact that this has happened at least twice seems like a testament, of sorts, to the sheer number of rides that Uber has done, and the number of chances it’s created for weird stuff to happen. And look, I am not here to tell you how to live your life, but if you’re going to sneak around, Uber—which has enough data to learn your routines and predict your destinations—seems like a poor way to do it.

Scooter spotting.

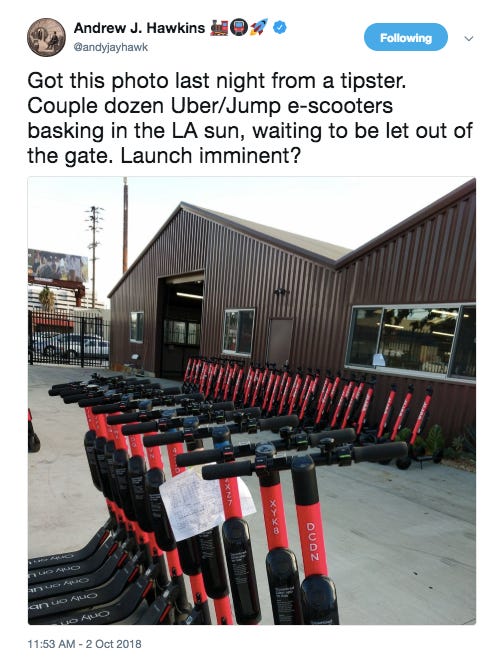

H/t (that is internet slang for hat tip, by the way) to Andrew Hawkins, who tweeted this photo he received of Uber/Jump scooters lined up in Los Angeles:

This time last year.

Why Ikea bought TaskRabbit, Uber to vote on board reforms, Ford CEO wouldn’t get in a driverless car

Other stuff.

Uber pays $148 million in data breach settlement. Uber overhauls business to cooperate with regulators in Germany. Uber returns to China to manufacture bikes and scooters. Uber may double Jump electric bike fleet in San Francisco. New York City considers legalizing standup electric scooters. Airbnb battles limits on short-term home rentals in DC. French hoteliers want Airbnb governed by real estate rules. Airbnb No Longer Just a Side Hustle for Many. French carpooling startup Klaxit partners with Uber to backstop rides. BlaBlaCar could be profitable in 2018. Uber crackdown in Spain hurting long-term unemployed. Uber hires Expedia exec to head human resources. Cargo raises $22 million for ride-hail vending machines. Jump installing bike racks in Sacramento. Men posing at Uber drivers sexually assaulted passengers in Pennsylvania. Amazon boosts minimum wage to $15 for all US employees. Money-losing companies are flooding public markets. The mystery of Tesla’s parked cars. “Don’t reflexively call an ambulance.”

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and scooter spottings to @alisongriswold on Twitter, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.