Uber’s self-driving cars are here, Lyft denies being for sale, and Postmates explains its “crystal clear” pricing

XXIV

Waiting for autonomy.

Last Tuesday (Aug. 16), Ford announced it would have fully autonomous vehicles on the road in five years’ time. Two days later, Uber one-upped the automaker with this splashy headline in Bloomberg: Uber’s First Self-Driving Fleet Arrives in Pittsburgh This Month. Uber’s first passenger-ready driverless cars will not be the hybrid Ford Fusion it released photos of in May, but rather “specially modified Volvo XC90 sport-utility vehicles outfitted with dozens of sensors that use cameras, lasers, radar, and GPS receivers.” The fleet is the result of a $300 million deal that Uber and Volvo reportedly signed earlier this year to create fully autonomous vehicles by 2021. For now the cars will travel with professional safety drivers and be deployed at random to Uber customers in downtown Pittsburgh. Also revealed in the Bloomberg story: Uber spent an estimated $680 million in July to acquire Otto, a driverless trucking startup founded by key former members of Google’s self-driving team.

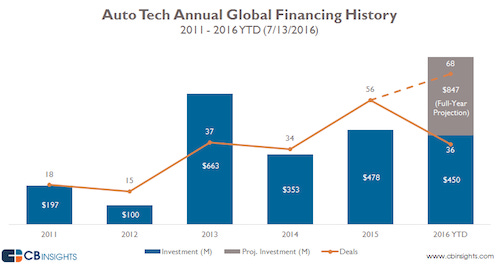

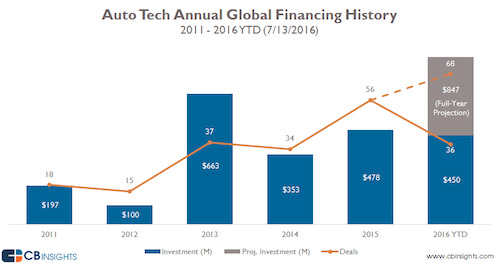

Companies from Google to Tesla to General Motors are rushing toward the driverless future; funding is flowing to auto tech at a record pace this year. It should be no surprise that Uber is determined to get there first. Travis Kalanick tells Bloomberg the issue of autonomy is “basically existential for us.” With Business Insider he is even more blunt: “If we are not tied for first, then the person who is in first—or the enemy that’s in first—then rolls out a ride-sharing network that is far cheaper or far higher-quality than Uber’s, then Uber is no longer a thing.” That is probably a fair statement, though it’s also worth considering this piece from Aaron Batalion of Lightspeed Venture Partners, who wonders whether Uber is hurtling toward its own destruction. Batalion’s argument is that the advent of truly autonomous, electric cars with singular uses like commuting could make the “fully loaded average cost per mile per passenger” of ride-hailing approach zero, at which point the dynamics of the transportation market would fundamentally shift:

One of Uber’s most impressive feats to date has been their ability to aggregate supply, e.g. drivers and vehicles, in hundreds of cities around the world. It has been a herculean effort — and often initially subsidized — to put available cars on the road. That said, as truly autonomous cars enter the market, another company could order a fleet of vehicles and put them online in a major city with just a checkbook, weakening Uber’s supply moat.

In the driverless future that Batalion imagines, rides are so commoditized that customers no longer even pay their negligible costs. Instead, monetization of trips goes the way of so many things on the Internet—toward sponsorships and ads. Starbucks throws in a complimentary ride with your morning coffee. Amazon makes them the latest benefit for Prime members. The content-creators provide the revenue for companies like Uber, and also become powerful gatekeepers of consumer demand. Something to ponder, regardless of whether you agree.

“Enough is enough.”

Here is a fun series of headlines:

Lyft Rebuffs Acquisition Attempt from GM (The Information, Aug. 12)

Lyft Is Said to Seek a Buyer, Without Success (New York Times, Aug. 19)

Lyft Was Seeking as Much as $9 Billion in a Buyout (Recode, later on Aug. 19)

Uber Tells Investors It Wouldn’t Pay Above $2 Billion for Lyft (Bloomberg, Aug. 20)

Lyft Pushes Back at Uber’s ‘Unsavory Tactics’ (The Verge, Aug. 21)

Lyft President: We Were Never Looking to Sell Our Business and We’re Not for Sale (Business Insider, Aug. 22)

To summarize, the Times reported Friday that Lyft had “held talks or made approaches to sell itself to companies including General Motors, Apple, Google, Amazon, Uber, and Didi Chuxing.” The Times didn’t name any figures but cited sources saying Lyft had struggled to find a buyer who would pay a premium on its latest $5.5 billion valuation. Then came Recode’s report and then Bloomberg’s and suddenly John Zimmer is denying all of it to Business Insider! A “large mischaracterization,” he says. “Enough is enough.” And: “I think it shows a bit of overstepping on Uber’s part with the Bloomberg story that fully demonstrates who is behind this.” That’s all very nice, but I doubt Zimmer’s comments to BI are going to convince anyone that the Times or Bloomberg reports were off-base.

Crystal clear?

Last week I wrote about Postmates, an Uber-for-anything company that promised to make on-demand deliveries cheap but that in reality deals in exorbitant fees and misleading prices. Postmates CEO Bastian Lehmann did not like this story very much. Specifically, he writes on Medium, it is “misleading and fundamentally incorrect in its assertions about our company.” I have read Bastian’s post several times and must admit I’m confused. He doesn’t actually argue any of the facts of my reporting or explain how Postmates is trying to make its pricing more accurate. What he does say is that the main incident detailed in the story—a Walgreens order that Postmates pegged at $48.96 and which ended up costing the customer $94.24—is a “good example of the complexity we navigate with every delivery and how our product is structured to ensure the fairest prices for the goods we deliver.” I guess that is one way to spin it? Here is my favorite part of his rebuttal (emphasis added):

When we are wrong with our prices, we ensure that we do the right thing. If our estimated price is too high the customer pays the lower price. Charging them the higher estimated price and keeping the money for the lower in-store cost would be unfair to the customer. If the estimated price is too low the customer pays higher price. Charging the customer the lower price would be unfair to us.

That is the customer-is-always-right spirit!

Elsewhere: Rob Kardashian Spent $13,000 on Postmates in One Month for Pregnant Blac Chyna.

Lease extensions.

This summer has not been the best for WeWork, what with it evicting a startup in New York, suing an ex-employee for disclosing information to reporters, and attempting to smooth over multiple reports that its business is missing important financial targets. Now the Information reports (paywall) that WeWork “has begun pushing to lock some companies into year-long rental agreements rather than month-to-month,” which would help protect it from sudden fluctuations in demand. WeWork says it would give tenants “small discounts” on their rents in exchange for the added security of a year-long commitment. Here’s a bit more:

in addition to smoothing out cash flows and sales costs, the move is also designed to help the company—which began as a solution for freelancers and small businesses—sign up larger tenants. Larger, “enterprise” tenants represent WeWork’s fastest-growing sales channel, and the company says close to one-third of its membership is comprised of tenants with offices of 15 people or more. Longer deals could also help lock down startups that grow in size.

For WeWork to justify its $16 billion valuation, it needs to prove it can be more than a glitzy startup incubator. The company has tried to diversify its offerings with WeLive, but early reports indicate that the business of selling glorified dorm rooms to wealthy millennials has been underwhelming. That makes WeWork’s ability to attract more mature, committed tenants to its core office-space operation all the more vital to the company’s long-term survival.

Other stuff.

Judge rejects Uber’s $100 million settlement with drivers. Decision “not a clean win” for Uber. Uber sues London over an English exam. Uber negotiates with Austin. Massachusetts makes Uber subsidize taxis. Lyft increases pick-up precision. Lyft halts Carpool service. Uber ups its focus on India. Ola shutters TaxiForSure. How Uber Rival’s Founder Won Friends and Influenced Beijing. Good Grocer partners with Instacart. Anaheim lets up on Airbnb. Amazon’s New Cooking Show Lets Viewers Order the Food. Foodpanda struggles to unload Indonesia business. Takeaway.com sells to Just Eat in the UK. Sharing Economy Tax Center. Flex work hours. Airbnb Trips. An Uber room of one’s own. “What does the typical Uber drive look like? We don’t necessarily know that.”