Uber wants to show you the money

“Ridesharing has been around for awhile, why isn’t anyone else profitable?”

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

This is the free edition of Oversharing. Become a paid subscriber to get two additional posts per week with the most in-depth analyses of the gig economy, mobility, and urban life; full access to the archive; and exclusive access to comments and community threads.

Jerry Maguire.

Uber investors are getting antsy about profits, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi wrote in a memo to staff on Monday:

While they acknowledge that we are winning, they don’t yet know the “size of the prize.” Their questions run the gamut from, “Has anyone other than you made money in on-demand transport?” to “Ridesharing has been around for awhile, why isn’t anyone else profitable?” They see how big the TAM is, they just don’t understand how that translates into significant profits and free cash flow. We have to show them.

Gosh, those are hard questions. Profits in ride-hail?

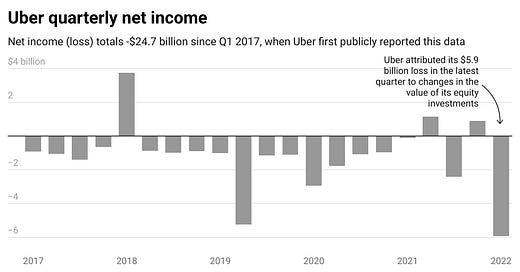

Uber Technologies Inc. currently has a market cap of about $45 billion, based on yesterday’s closing share price of ~$26. By comparison, Uber’s total net income since Q1 2017, the first quarter for which it publicly shared financial data, comes to -$24.7 billion. To be clear, that includes the quarters for which Uber reported a profit. Uber’s net losses alone since Q1 2017 total -$30.5 billion.

To put that in context, here are some other things worth about $24.7 billion:

The market cap of Delta Air Lines

The GDP of El Salvador

The net worth of He Xiangjian, the world’s 49th richest person

365,812 times the U.S. median household income

These are crazy numbers, even in a system of Silicon Valley capitalism distorted by huge infusions of private financing. Uber has always said it would reach profitability at scale, thanks to network effects, etc., but what is scale if not a company that operates in 72 countries and more than 10,500 cities, which last year had 118 million active users every month and completed 6.3 billion rides/trips/deliveries? Uber is the definition of scale, yet it is still nowhere near consistent and reliable profitability. This is not for lack of trying. Uber has unloaded its driverless car unit, offloaded e-bikes and e-scooters, strategically exited food delivery markets, and gone through several rounds of layoffs. In late 2019, Khosrowshahi predicted Uber would be profitable on an adjusted basis for the full year 2021. Then the pandemic happened, and he adjusted expectations to a single adjusted ebitda profitable quarter by the end of 2021. For the full year, Uber lost $774 million on an adjusted basis.

So what’s the plan? “Channeling Jerry Maguire, we need to show them the money,” Khosrowshahi writes. Company goals include faster growth in delivery and stronger results and greater recognition of the freight segment. Uber will also cut costs by slowing capital investments, cutting spend on marketing and incentives, and restricting hiring. “We have to make sure our unit economics work before we go big,” writes Khosrowshahi, apparently forgetting that Uber has already gone big.

But hey, look, it could happen. Uber made some good progress in 2021. Adjusted ebitda profit increased for the mobility (rides) segment, despite increased driver incentives lowering the take rate. Adjusted ebitda loss for delivery, meanwhile, shrunk and take rate increased thanks to more orders, bigger basket sizes, and less spending on incentives. As we talked about this weekend, Uber seems to be in a good position in terms of driver (“earner”) supply, especially compared to Lyft. So sure, ok, show them the money. Though as a side note it is unclear to me if the writer of this memo has seen Jerry Maguire—Jerry is not exactly thrilled, one might even say distressed, when his client Rod Tidwell instructs him to “show me the money.” I am not sure this comparison is doing Uber any favors in terms of investor confidence. I know this because I watched every Tom Cruise film on Netflix during lockdown, which I never thought would be relevant to writing about Uber, but life is full of surprises.

E-bikeshare.

Several urban U.S. bikeshare programs are getting an e-bike upgrade:

Pittsburgh launched a new bikeshare system, POGOH (a name meant to evoke a pogo stick, bikeshare director David White told the local paper), which includes e-bikes that go up to 20mph. Pittsburgh is very hilly, which makes e-bikes a particularly nice addition. “We want people to get around more easily,” White told the local paper. “These bikes are perfect for a new cyclist or a senior cyclist.” The city bikeshare program currently includes 38 stations and 350 bikes, of which more than half are e-bikes; there are plans to add another 27 stations and more than 160 bikes in the fall, with half being e-bikes. A regular annual membership costs $120 per year, with subsidized $10/year “Mobility Justice” memberships available to low-income residents.

Chicago’s Divvy bikeshare system became the first in the U.S. to install e-bike charging stations, with five installed and plans to add more. The charging stations are designed to reduce carbon emissions related to swappable batteries, which is how most shared e-bikes are currently maintained, and will also presumably reduce operating costs for Divvy bikeshare operator Lyft. VC-funded bikeshares have their roots in the dockless model, thanks to the influence of Chinese operators like Mobike and Ofo, but docking stations make a lot of sense. Stations help to solve common complaints about cycle parking and seem like a logical way to deal with charging issues, especially if the stations are placed at high-use areas where rebalancing is less of a concern.

New York City’s Citi Bike, another Lyft contract, is getting a snazzy new fleet of e-bikes with 60 miles of assisted riding per charge and frames painted with reflective paint. Citi Bike currently counts 24,500 bikes (regular and electric) and more than 1,500 docking stations. Ridership surged during the pandemic, with a peak of 631,314 weekly rides during one week last May. Citi Bike raised the price of an annual membership to $185 plus tax in January, up from $179, a change it attributed to increased supply chain costs. Meanwhile, the city Parks Department is still trying to figure out whether to allow e-bikes to be used in city parks and greenways, where any sort of motor vehicles—e-bikes included—are currently prohibited.

Exits.

Lime has quietly shuttered its shared electric moped service in New York City after less than a year, amNewYork reported:

The company withdrew its vehicles starting in late winter, shifting gears to focus on a pilot with the city to bring electric standup scooters to parts of the Bronx, according to a Lime spokesperson.

“We recently made the decision to wind down our moped program in New York City and focus entirely on the city’s e-scooter pilot program,” Jacob Tugendrajch told amNewYork Metro in an email.

Lime pitched its green mopeds as a safer version of the blue ones offered by rival moped startup Revel, whose mopeds have been accused of dangerous malfunctions and linked to a series of injuries and deaths. It is unclear exactly what made Lime’s mopeds safer, as according to amNY they were made by the same Chinese manufacturer NIU used by Revel, but they were slightly cheaper, with a price point of $0.10 less per minute than Revel’s.

Other stuff.

Uber shareholders vote on lobbying disclosure proposal. Uber Repairs Paris and London Relationships With EV Push. Uber seeks to resolve dispute with Kenyan drivers via arbitration. UK mobility startup RideTandem raises €2 million to tackle transport poverty. Instant grocery delivery startup Zepto raises $200 million to expand service in India. SoftBank-backed ghost kitchen laying off 5% of employees. DoorDash beats earnings. Lyft bringing shared rides back to several U.S. cities. San Diego proposes new rules for e-scooters. DoorDash cuts deal with Australian Transport Workers’ Union. Just Eat Takeaway faces shareholder backlash. Instacart lands partnerships with all of Canada’s biggest grocers. Marriott takes on Airbnb by offering private home rentals. Airbnb commitment to ‘work from anywhere’ draws 800,000 views to careers page. New ride-hail company lets drivers drive for a monthly subscription fee. DoorDash driver carjacked in North Carolina. Exploding e-scooters kill four as heatwave damages batteries. Food delivery by plane in remote Alaskan villages. Uber salaries. Unagi on Demand. Hudson Valley council member who fought against Airbnb caught listing home on Airbnb.

I would say I sound like a broken record but that would give away my age, and erode my cred, which is already abysmal. So I'll just say I will repeat myself. Taxi economics: cost of car, cost of driver, cost of gasoline, plus minimal (dispatch and maintenance) overhead = minimal profit and no particular scale economies beyond any one city. Uber economics: cost of car, cost of driver, cost of gasoline, plus massive corporate overhead = significant losses. And if no particular advantage to scale (as Ms. Griswold points out), then why would Uber (the ridehail part, not the delivery part) ever make money? The things they do at the margin to be more efficient than taxis (e.g. algorithmic tweaking of drivers and cars) don't move the needle enough to offset costs like paying a CEO $20 or $40 million (let alone the other 25,000+ Uber employees (not counting drivers oops I mean earners)). Short of the eventual Holy Grail of driverless robotaxis, how does any ridehail company fundamentally alter the cost triad of fuel, driver, and car?

One of the biggest variable areas of expense is the insurance costs - would be interesting to hear your take on that side of the equation!