Uber made surge pricing so mainstream, even the Fed is talking about it

Score a big win for Ubernomics

Earlier this month, Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari published an essay on where the Federal Reserve went wrong on inflation. Kashkari wrote that many inside the Fed, himself included, were caught off guard by how quickly inflation surged, and missed again by assuming it would recede equally fast. He offered this analogy:

One feature of ride-sharing apps such as Uber and Lyft is “surge pricing”: When an unexpected rainstorm hits, people don’t want to walk or ride bikes. They call for cars, and the price of a ride can surge from, say, $20 to $90. The high price accomplishes two goals: First, it reduces demand, and second, it incentivizes all available drivers to come out and increase supply. The market then clears at the elevated price. I don’t consider surge pricing to be nefarious. I consider it economically necessary given supply and demand dynamics.

Imagine a rainstorm hits, and the price surges from $20 to $90. But imagine, in my analogy, the ride-sharing company owns all the cars, and the drivers are its employees. When the storm hits, the company notifies all their drivers that they will pay time and a half. So, all the drivers come out to drive. The company doesn’t raise wages even more because they are car constrained: All their cars are deployed.

My story is of course too simple—just a demand surge, rather than both increased demand and disrupted supply—but the resulting characteristics resemble the economy we have been experiencing: Prices soar. Corporate profits climb. Income for drivers climbs, but not as much as prices. Real wages actually fall. Even though worker incomes are up, labor’s share of income is down. Labor markets are tight, but capital is the constraint on supply. Inflation has soared, but it soared because of supply/demand dynamics—what I will call “surge pricing inflation.”

I mention this not to talk about inflation but rather because this essay is a huge win for Ubernomics. I profiled Uber’s in-house team of economists (officially “Research and Economics,” but I prefer Ubernomics) back in 2018 for Quartz. I would never suggest you read everything I wrote for Quartz because frankly a lot of it was pretty mediocre and produced purely to meet the demands of digital content creation. But Ubernomics was one of my best Quartz stories and if you haven’t read it already I would recommend it.

Here’s an excerpt:

Uber is so fond of economists that it employs more than a dozen PhDs from top programs at its San Francisco headquarters. The group acts as an in-house think tank for Uber, gathering facts from quants and data scientists and synthesizing them to arm the lobbyists and policy folks who fight some of Uber’s biggest battles. Officially, this team is known as “Research and Economics.” Internally, it’s also been called Ubernomics.

Ubernomics keeps a low profile, despite the fact that Uber has collaborated on research papers with economic superstars like Levitt and former Obama adviser Alan Krueger. Its wide-ranging mandate includes studying the consumer experience, testing new features and incentives, supporting Uber’s public policy needs, and producing peer-reviewed academic research.

Plenty of companies hire experts to bolster their business, but Uber wants prestige, too. It wants its papers authored by the best and brightest, and accepted by leading academic journals. Prestige, after all, confers legitimacy, and this sort of soft power is the perfect complement to Uber’s hard-charging politics. The mission of Ubernomics is simple: to prove, with cool and unemotional logic, that the rest of the world should love Uber as much as economists already do.

One of the first missions of Ubernomics was to make a case for surge pricing. Before Uber, the idea that for-hire rides would be priced dynamically and as such might cost more when it rained, or right after a concert let out, or because of many other things that routinely affect taxi demand patterns, was pretty unheard of. On the contrary, taxi service in most U.S. cities was tightly regulated, with fixed numbers of cabs and licenses, and fares calculated using metered rates for time and distance. So heavily regulated was the taxi industry that it routinely appeared in the economic literature as an example of regulatory capture.

Surge or dynamic pricing was a core Uber feature from the beginning, as well as a pet policy of Uber’s co-founder and CEO. Travis Kalanick, then a prolific Twitter user with an Alexander Hamilton avatar, could frequently be found defending surge online, arguing that it was essential to Uber maintaining a reliable service and to bringing driver supply online in times of high demand. It was, he liked to say, “econ 101.”

In the early Uber years, surge pricing played out most prominently on New Year’s Eve. Ahead of the December 2012 holiday, Kalanick (“Travis”) wrote a blog post to the “Uber Faithful” explaining that “Ubers are going to be pricey” and “NYE pricing is not for the faint of heart”:

The average surge multiple will be about 2x normal prices, during the worst times (12:30 AM until 2:45 AM), but prices during extreme spikes could cost you $100 MINIMUM before time and mileage charges! These are limos, people, so be careful with those Uber ride requests: Uber rides will be reliable on New Year’s Eve, but they’ll also be pretty pricey.

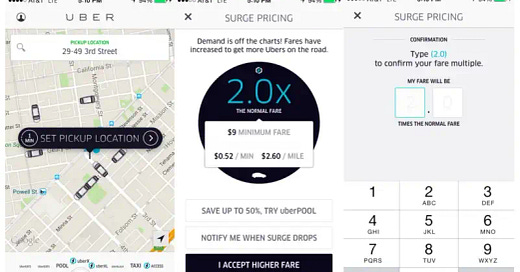

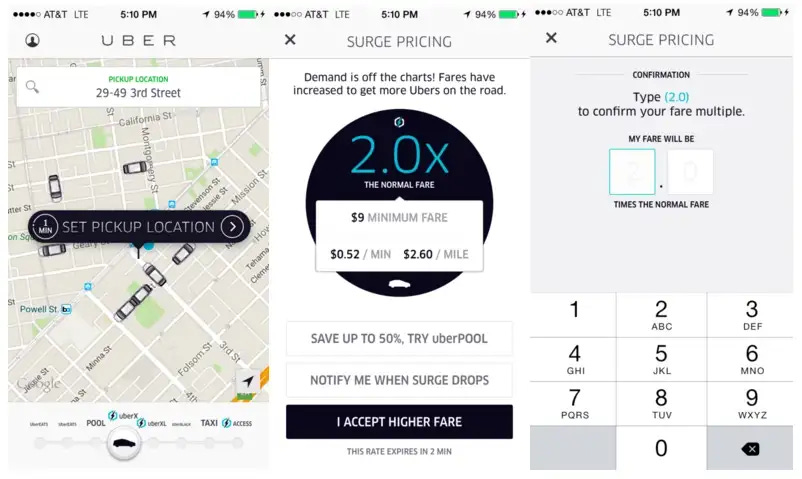

In a “surge pricing Q&A,” Kalanick reiterated the thesis that surge allowed Uber to “ALWAYS connect you with a RELIABLE RIDE – even on New Year’s.” The post also explained that riders would see and be asked to accept the fare multiplier before booking a ride, and to pass Uber’s “sobriety test” when multiples “get really high.” (Another classic Kalanick talking point was that people—in this case, drunk ones—should stop blaming Uber for things and take responsibility for their own shit.)

That surge pricing might make sense in economic theory didn’t make it popular. It turns out that the economic theory of textbooks is not always palatable to people in real life. And while raising prices to clear the market might be logical in a tech bro’s libertarian fantasy, to those outside the Silicon Valley bubble (and even to some inside!) it reeked of price gouging and discrimination. What Kalanick saw as charging the market’s ‘willingness to pay’ in times of high demand was for many a question of ‘ability to pay.’ As one Twitter user put it in December 2013, surge separated Uber users into “‘only the rich’ vs ‘you wait just like everybody else.’” Uber’s uncompromising approach to New Year’s Eve was, in retrospect, the first sign that while the company marketed itself as an everyman’s service (faster and cheaper than a taxi!), under pressure it was a luxury good.

Surging prices for New Year’s revellers was one thing, but when Uber hiked fares during extreme weather and emergency situations, regulators took note. Incidents included Uber putting 7x multipliers on fares during a nor’easter in 2013 and quadrupling prices in Sydney, Australia, near the site of a deadly hostage siege in December 2014. By then Uber had caught the eye of then-New York state attorney general (and later alleged sexual abuser) Eric Schneiderman, who cut a deal with the company to limit price increases during state-declared crises in summer 2014 and again ahead of a major January 2015 snowstorm.

And so for a brief moment in late 2014-early 2015, it seemed as though both public opinion and political and regulatory power might turn against surge, forcing Uber to overhaul its pricing model. This is where Ubernomics comes in. In September 2015, Uber released a short white paper, “The Effects of Uber’s Surge Pricing: A Case Study.” The paper was written by two researchers at Uber and co-authored by an assistant professor at the prestigious University of Chicago Booth School of Business. It claimed to use internal Uber data to show “the power of surge to equilibrate supply of and demand for rides with Uber.”

The paper compared Uber data from two events: a sold-out Ariana Grande concert at Madison Square Garden in March 2015 and New Year’s Eve 2014-15 in New York City. The paper explained that the surge algorithm allowed Uber to manage a huge spike in demand after the Ariana Grande concert—keeping ETAs low and completion rates high—by bringing more drivers online and to the area, and limiting ride requests to “those that value them most,” such that “everybody that wanted an Uber ride (at the market clearing price)” was able to get one in an average of 2.6 minutes.

The authors contrasted the ‘success’ of surge after the concert with a 26-minute window in the early hours of Jan. 1, 2015, during which Uber’s surge algorithm broke down, leading ride requests and ETAs to soar while completion rates plummeted. It turned out that when an Uber ride wasn’t exorbitantly expensive—which, let’s recall, it usually wasn’t thanks to immense VC subsidies that allowed Uber to make the service cheaper than a taxi—lots of people wanted one, far more people than Uber could accommodate. Once surge pricing came back online, however, a lot fewer people wanted a very pricey ride, which meant that Uber could fulfill a higher share of requests and book a better completion rate—surely good for the metrics it pitched to VCs on its endless quest for financing. (The authors also theorized that the brief surge outage caused the supply of drivers to dwindle, but had no evidence for this, as “unfortunately the same technical flaw that inhibited surge also inhibited the collection of [driver supply] data.”)

Flimsy as that paper may seem now, it gave Uber exactly what it needed at the time. Ubernomics handed the research off to policy operatives, who used the paper to talk down politicians who were weighing broader restrictions on surge pricing. Uber repeated the playbook on other contentious issues, producing research collaborations with esteemed academics and institutions that bolstered its policy positions and made a case for the Uber business model.

By now most of this is ancient startup history, but I’m telling you all of it to underscore the point that for a Fed official in 2023 to explain inflation in the language of Uber and surge pricing is a big fucking win for Ubernomics. It’s proof that the soft power and legitimacy has stuck; that a once brash and controversial business practice has been parlayed into the mainstream. Here is the president of the Minneapolis Fed repeating as fact Kalanick’s defense of surge pricing and rubber-stamping it for the economic elite. What more could a corporate research team want?

It is amazing, or maybe not, how many times we have to re-re-learn all the basics (and not-so-basic nuances) of taxi regulation. Of the endless juggling of enough vehicle availability to maintain high service levels versus keeping supply low enough to reduce dead-heading, all while trying to provide drivers a living wage without the fleet owners doing their regulatory capture thing and with lower-income people not being priced out... See this brief historical view (just Google "Why TNCs Will Be Regulated Like Taxis–Historically Speaking") and check out its bibliography, if you (not Ms. Griswold, she already knows this stuff) want to see the long painful saga.