Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy.

If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. This is issue 103, published May 15, 2018.

Uber moves forward.

To use Uber, riders and drivers have historically had to sign a long list of terms and conditions that included an arbitration agreement. Under this agreement, you waived your right to sue in open court and agreed instead to resolve any disputes with Uber in a private process known as arbitration. And it's not just Uber. We agree to arbitration when we buy phones, apply for credit cards, shop online, and, for a time, even when we downloaded coupons for cereal.

Lately mandatory or "forced" arbitration has gotten more attention for its role in covering up sexual harassment and assault. The arbitration provisions that consumers agree to, as well as the ones buried in employment contracts at many companies, tend to prevent victims of sexual misconduct from filing complaints. Forced arbitration in employment contracts also typically goes hand-in-hand with nondisclosure agreements, which help ensure that any incidents are kept quiet.

Last month, Susan Fowler, the former Uber engineer who in 2017 authored a viral blog post about sexual harassment she endured at the company, penned an op-edfor the New York Times on how to stamp out such behavior. “We need to end the practice of forced arbitration,” she wrote in the op-ed, “a legal loophole companies use to cover up their illegal treatment of employees.”

Today Uber said it's doing just that. The company will no longer require its US riders, drivers, or employees to arbitrate individual claims of sexual assault or harassment, chief legal officer Tony West announced. It will also stop requiring confidentiality provisions on claims of sexual misconduct. Uber said the changes won’t unwind previous settlements, but will apply to all future complaints, effective immediately.

Uber rarely takes the lead on social progress. A year ago it was widely regarded as one of the most toxic workplaces in Silicon Valley, and when change did start to happen it felt reactive, not proactive. But by eliminating forced arbitration, Uber is suddenly at the forefront of a national movement to rethink how corporate America deals with sexual harassment. “The last 18 months have exposed a silent epidemic of sexual assault and harassment that haunts every industry and every community,” West said. “Uber is not immune to this deeply rooted problem, and we believe that it is up to us to be a big part of the solution.”

In addition to eliminating mandatory arbitration, Uber also plans to begin making public a safety report that will detail sexual assaults on the ride-hailing platform, as well as other still-to-be-determined categories of incidents, something none of its competitors currently do. The first report, when published, could very well be shocking, in part because Uber is an imperfect platform where random strangers interact and bad things can happen, and in part because Uber does billions of trips and, statistically speaking, bad things are bound to happen.

When Travis Kalanick took a leave of absence in June 2017, before he was pushed out as chief executive, he said he needed to work on "Travis 2.0" so Uber could become "Uber 2.0." I joked at the time about Travis 2.0, a sensitive guy who respected women, cooperated with local governments, and always tipped his driver 20%. But the transformation that Uber has undergone since Dara Khosrowshahi took the CEO job nine months ago seems beyond anything Travis 2.0 could have even imagined. (Speaking of Travis, he was reportedly last spotted partying at the Cannes Film Festival.)

A day before its arbitration announcement, Uber launched a new ad campaign featuring Khosrowshahi and titled, "Moving Forward." In a video posted to YouTube, Khosrowshahi introduces himself and says it's time for Uber to move in a new direction. "I want you to know just how excited I am to write Uber's next chapter with you," he says, while contemplating the passing view from his window. "One of our core values as a company is to always do the right thing. And if there are times we fall short, we commit to being open, taking responsibility for the problem, and fixing it." It's sappy stuff, but it's also effective. It's hard to see any version of Travis pulling that off.

Be your own boss.

Elsewhere in Uber, here is a new study from the Economic Policy Institute, a pro-labor think tank, that finds Uber drivers earn $10.87 an hour after expenses, and $9.21 an hour if you adjust for what an independent contractor might pay out of pocket for a modest benefits package.

The question of how much Uber drivers make has always been a ripe topic for discussion. The number has been argued over extensively and is hard to pin down for many reasons, including:

Uber pays different rates in different markets

A lot of driver income is tied up in limited-time promotions and incentives

Uber has repeatedly changed its commission structure and, consequently, how drivers are paid

Drivers pay their expenses out of pocket, which requires estimating things like gas and depreciation

Uber controls all the data

Uber has shared a bit of data on driver earnings in various economic papers, usually through collaborations with respected academics, but the figures it has given out can be hard to compare. A January 2018 paper that Uber collaborated on used "gross earnings" ($21.07 an hour) taken before deducting costs such as gas, vehicle depreciation, and Uber's service fee. Research from Uber's team and Princeton economist Alan Krueger has used earnings "net of Uber's fees" but before driver expenses ($20.19 an hour).

You might remember that, back in March, a study from MIT's Stephen Zoepf claimed that the median profit from driving for Uber or Lyft was $3.37 an hour. The methodology behind this assertion proved to be severely flawed, and after identifying the error and redoing the calculations, Zoepf increased his estimate of median hourly driver profit to between $8.55 and $10.

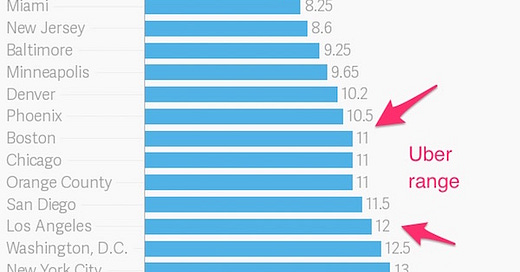

While the numbers from Uber vs. independent third parties seem far apart, they aren't actually so different. The Krueger paper, for example, estimated on-the-job expenses at a midpoint of $3.60 an hour for a part-time driver and $5.10 an hour for a full-timer. If you take Uber's latest gross earnings figure ($21.07 an hour), adjust it for an assumed a 25% commission (not how this works anymore, but fine for an estimate), and then deduct between $3.60 and $5.10 for expenses, you come up with net hourly earnings of $10.70 to $12.20. That's remarkably similar to the numbers put forward by both MIT and EPI.

It's significant that these numbers are all relatively in line because it allows the debate to move, finally, from how much Uber drivers make to how much Uber drivers should make. Many people have long suspected that being an Uber driver isn't a great gig, but it's been hard to prove because there wasn't much consensus around the hourly earnings. But if we accept $10.70 to $12.20 as a reasonable range, we can make certain observations, for example, that $10.70 isn't less than the US federal minimum wage, but is below the local wage floor in many major cities, such as New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and Boston.

Last August, it came out that Uber in an internal presentation on driver income had pointed to Lyft and McDonald's as the greatest competition for workers. McDonald's pledged in 2015 to pay all workers at US company-owned stores at least $1 an hour above the local minimum wage. While workers claim McDonald's hasn't always kept up, it seems safe to say you could make as much—or more!—flipping burgers in many big American cities as you could driving for Uber.

As Uber has said a truly interminable number of times, drivers like the flexibility they get from working for Uber, and it's true that a job at McDonald's doesn't come with anywhere near that amount of freedom. The low-wage economy is notoriously unforgiving of workers who show up late or miss a day, regardless of the reason. Uber will penalize you for driving unsafely, but never for choosing to skip a day to care for a sick family member. On the other hand, I think we can now fully dispense with the myth that driving for Uber is a lucrative job. Uber is another facet of the low-wage economy, not a modern American dream, whether it likes it or not.

"Cereal saved the company."

Airbnb has a new font, called Cereal:

"We sought to imbue a playful, open, and simple typeface with a touch of quirk," says Derek Chan, Airbnb's creative lead on the font. "It brings us back to the early days when breakfast was a part of our name, and is also a nod to a time when cereal saved the company." (Airbnb's co-founders sold boxes of "Obama O's" as an advertising stunt at the 2008 Democratic National Convention.) "We explored a few traditional naming territories, but ultimately the story and the name represent our values and sentimentality," Chan said.

Look here it is:

Airbnb says the font took about a year and a half to develop, in partnership with international type foundry Dalton Maag. Chan says Cereal "stands out by representing our values," and I mean sure, I look at this font and I see inclusivity, belonging, a global community, open arms, friendly buildings, adventure, travel, companionship, family memories, design, innovation, inspiration, disruption, balance, harmony, world peace. You know, about the same the range of emotions you feel when you pour a bowl of Cheerios for breakfast.

Free Enterprise.

One fun thing about the sharing economy is how the same stories play out over and over again. A startup comes along and scares an incumbent with its slick technology and consumer-friendly service. The incumbent, worried about the new threat, calls up its friends in politics and gets them to introduce new bills or declare support for existing legislation that makes it harder for the startup to break into the business. We've seen this play out with taxis, hotels, even dog-sitting (those kennel licensing laws are no joke).

Anyway, it's also happening right now with rental cars. Enterprise Holdings, the parent of Enterprise Rent-A-Car and biggest rental car operator in the US, has backed legislation in at least half a dozen US states that would subject car-"sharing" startups to a long list of rules and regulations. Enterprise and its affiliates at the American Car Rental Association say they're acting out of concern for consumer safety, but startups like Turo that allow private car owners to rent out their vehicles say the rental car firms are scared of the tech threat.

Enterprise is still solidly at the top of the market—it did $22.3 billion in global revenue and grew its North American business last year—but it's seen the writing on the wall. Already, ride-sharing has decimated the market for rental cars among business travelers. Meanwhile, the market share held by rival firms Hertz and Avis Budget Group is shrinking. Consumers have little love for Enterprise, which has a dismal average rating of 1.5 stars over the last 12 months on Consumer Affairs, and are more open to sharing assets than they have been in the past, all a threat to the traditional rental car model.

Even the auto industry looks down on rental cars. The same day we published this story (May 10), I went to a breakfast event with Julia Steyn, CEO of GM car-sharing service Maven, where someone asked about whether she saw rental car companies as the primary competitors. "Not at all," she said. "The only thing they care about is which price point they buy a car at, and which at which residual value they sell it. They're not building their business around… dollars per mile, and frankly they couldn't care less."

"And for the human interaction, I don't know if any of you have done Avis or Hertz," she added. "I mean, that's not what a modern millennial wants to do. It's not app-forward, you have to go into some gated something and interact with a human being who's trying to sell you insurance." God forbid.

Other stuff.

Didi Chuxing slammed for response to a female passenger's murder. Waymo tells police how to break into and disable its driverless cars. Filings reveal new details on Waymo fleet. Vacation rental site Tripping lays off 30% of staff. Thumbtack launches "instant results". Ofo tries for low-income riders with service in Camden. Why Seattle Is America's Bus-Lovingest Town. Uber's future won't just be cars. Lyft claims to have 35% of US ride-share market. Didi gets permit to test driverless cars in California. Senior Tesla executive leaves for Waymo. US appeals court revives challenge to Seattle law that lets Uber drivers unionize. Seattle loss could spur more laws that let Uber drivers organize. WeWork's lucky number proves anything but lucky for bond sale. Spain cracks down on Airbnb. Amazon drops third-party vendors from Fresh. Uber rejected Michael Cohen multiple times. Google and Levi's Connected Jacket Will Let You Know When Your Uber Is Here. "Markle will be the first gig-economy aristocrat." "What planet is Bill Gurley living on?" Wall Street Is So Sure MoviePass Will Fail, It's Become Incredibly Expensive to Short.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and Cerealized fonts to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.