Uber ends fare cuts in New York, Airbnb raises the white flag, and a leaked Postmates pitch deck

XXXVII

Hello from San Francisco, where both the burritos and the UberPools are immeasurably better than in New York.

Home-sharing.

Airbnb is in the midst of a dramatic reversal on home-sharing regulations. After battling them for months, the company has started cutting deals. It introduced a “One Host, One Home” feature in New York and San Francisco that prevents hosts there from listing more than one entire home. It agreed with London and Amsterdam to ensure hosts meet local licensing requirements and to enforce caps on the number of days an entire apartment can be rented out each year. Over the weekend, it settled a vitriolic spat with New York, agreeing to drop its lawsuit over stringent short-term rental regulations in exchange for the city promising only to fine hosts for violations, and not the company itself.

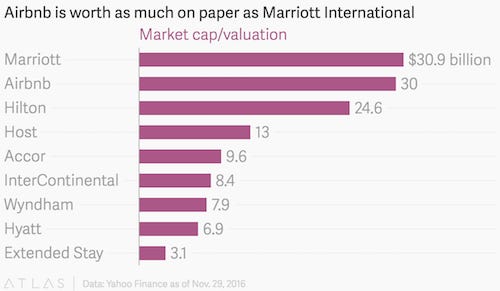

What happened? Forced into a corner by city regulators, Airbnb acted like a real corporation: it stopped being polite and started getting real. (Yes, you should click that link, which goes to my 3,000-word feature on this topic.) Airbnb has branded itself as a defender of the middle class since its founding during the Great Recession, as millions of people who’d lost jobs, homes, and savings were looking for a way to get back on their feet. The company has stuck by that image for nearly a decade, even as it matured from a humble startup to a $30 billion business, worth as much on paper as Marriott International, the world’s largest hotel chain.

For a long time, the interests of Airbnb and its hosts were perfectly aligned: putting hosts first was the way to get more hosts, which meant more bookings overall and, for Airbnb, more revenue. But as regulators have cracked down on home-sharing in some of Airbnb’s biggest markets, corporate imperatives and champion-of-the-middle-class branding have gotten tougher to square. I think Scott Shatford, founder of analytics site Airdna and the first person to be prosecuted for illegal Airbnb rentals in Santa Monica, California, put it best. “Obviously, their hosts are the lifeblood of their business,” he said. “But you’ve always got to weigh the pros and cons of when you’re going to back your hosts, and when you’re going to back your company.”

Ebitduh.

I’ll admit, I was surprised when Postmates in late October said it had raised $140 million in its latest round of funding. The number I’d heard floated was closer to $100 million, and 2016 wasn’t exactly a good time to be seeking money as a food delivery startup. Postmates CEO Bastian Lehmann admitted as much to Bloomberg, calling the round “super, super difficult,” and to Fortune, whom he told, “flat is the new up.”

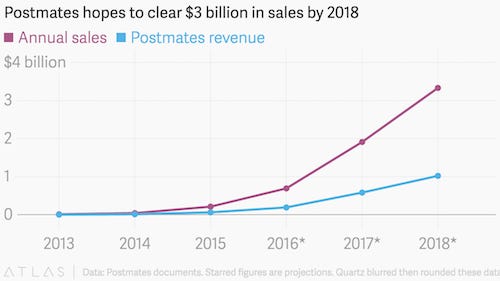

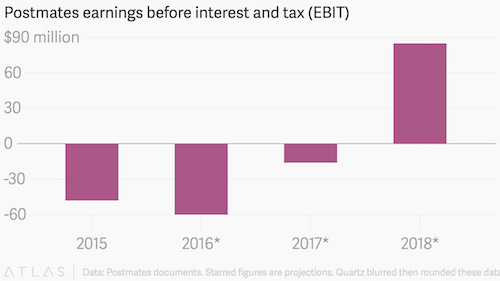

Here’s a little more info: I got ahold of a Postmates presentation dated to this summer and the company sold a very rosy vision of its future. In 2015, Postmates lost $47 million before interest and tax on revenue of $52 million, according to the slide deck. For this year, it projected losing nearly $60 million before interest and tax on revenue of close to $200 million. But by 2018! Give it two years, and things were looking grand. Postmates predicted annual sales rising 400%, and its own take increasing by even more. It also forecast earnings (before interest and tax) turning positive for the first time, to the tune of nearly $90 million.

Sure, those charts look good, but how does Postmates plan to get there? That was much less clear in the presentation. Making deliveries more efficient, cutting spending on customer service, lowering onboarding costs for couriers (which still top $120). I don’t know, it really seems like they’re going to need more than that. The entire thing reminds me of something a startup exec said once when we were talking about how companies get funded. Startups, this person said, are in the business of pitching aspirational unit economics. I think we can agree that Postmates’ numbers are nothing if not aspirational.

Fare hikes.

We’ve talked before about how ride-hailing is a uniquely brutal business: low-margin, easy to enter, tough to differentiate, and won mainly by undercutting the competition. Uber, Lyft, Didi, Juno, you name it—all have spent heavily on subsidies to make fares more attractive to riders and wages at least tolerable to drivers. But the golden era of discounting appears to be nearing its end. In India, Ola is rolling out new entertainment features for riders as it attempts to wean them off price-based incentives. In China, Didi Chuxing has ended certain subsidies for drivers and raised prices for riders since it acquired Uber’s China business this summer. In New York, Uber general manager Josh Mohrer has reportedly told the city’s drivers that the company is done cutting prices, something it’s historically done every January.

Of course, it was never realistic to expect ride-hailing companies to subsidize their business forever, so the question is what happens when those incentives go away. Do drivers keep driving (at least until autonomous cars take their place) and riders keep riding, because habits have been formed and they’re willing to pay a premium for convenience? Or do a lot of users desert the platforms? I guess we’ll have to wait and see.

Brand envy.

Some interesting Instacart news buried at the bottom of this Wall Street Journal story on Amazon’s big push into grocery:

Target in recent months began considering a pilot to deliver its own groceries, which face declining sales as too few shoppers are buying perishable items like milk and eggs. But it hasn’t moved forward with the idea, according to a person familiar with the matter … The retailer currently offers a grocery-delivery service in select cities through a partnership with Instacart Inc., a grocery-delivery startup. However, executives are concerned the service is boosting Instacart’s brand rather than the retailer’s own brand, according to the person.

This is obviously bad news for Instacart, which from the start has positioned itself as a consumer-facing brand, rather than a backend logistics service. On the other hand, as Target looks to compete against the likes of Walmart and Amazon on grocery, it’s not exactly in their best interest for customers to say, “you know, I need groceries, and I’m going to order them from Instacart, and I guess it’s OK if they come from Target.” No, Target wants people to want to get their groceries at Target. A backend logistics service might be just what it needs.

Other stuff.

Driving for Uber is the modern elevator pitch. Uber Wants to Track Your Location Even When You’re Not Using the App. Lyft adds upfront pricing. Trump’s transportation secretary could be good for Uber and Lyft. BMW seeks to be “coolest” ride-hailing service. Otto truck completes highway run in Ohio. Uber threatens to leave Maryland over background checks. Michigan wants to regulate Ubers like taxis. Instacart shoppers sue, again. Growth stalls at Rocket Internet. Zenefits burns cash. Amazon is a transportation company. Uber’s new AI lab. Riding This Self-Driving Scooter Could Mean You Never Have to Walk Again. It’s Not Ok That Customers Can Order Three-Tier Cakes on Postmates. “It was impossible to tell if any of the 15 judges presiding over a critical case for the ride-hailing company Uber had ever used the service.”