Traffic cones vs. self-driving cars

The battle of our era is playing out on the streets of San Francisco

Self-driving cars have met their match in the form of the humble traffic cone.

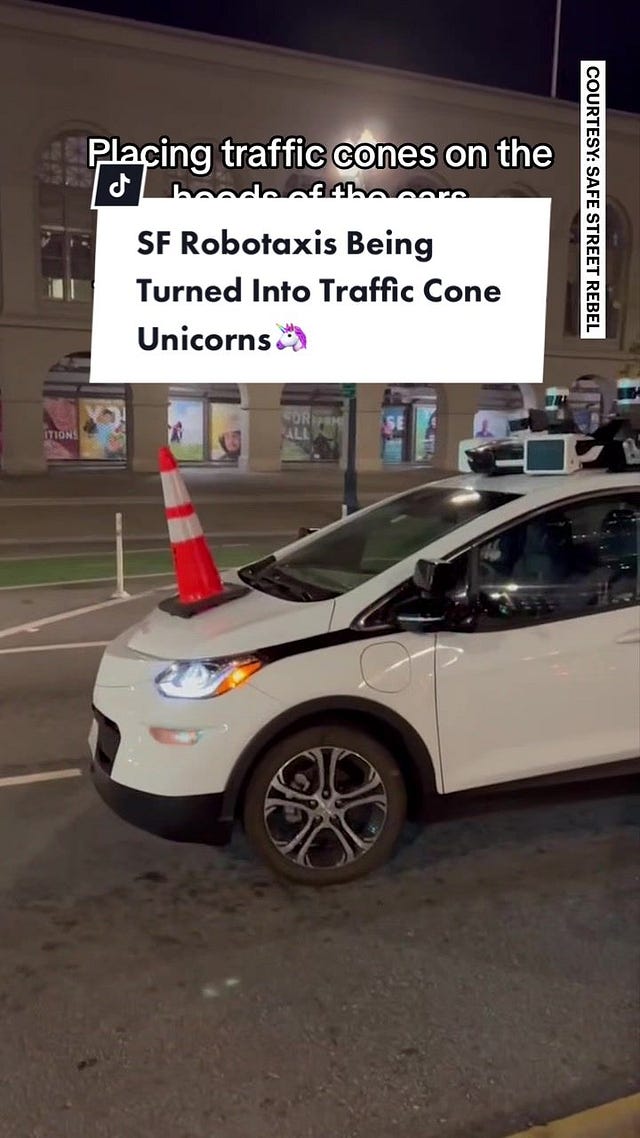

If you’re on TikTok, you may already know what I’m talking about. If not, please take a moment to enjoy this viral video of San Francisco activists disabling autonomous Cruise and Waymo vehicles by placing bright orange traffic cones on their hoods.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The cones immobilize the AVs (that is shorthand for “autonomous vehicles”) by forcing them into “shutdown mode” with their hazard lights on, “until the cone is removed or a company technician comes to reset the car's system,” the San Francisco Standard reported. Safe Street Rebel, the group behind the stunt, unleashed the cones last week ahead of a scheduled July 13 vote by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) that could allow Cruise and Waymo unimpeded access to public streets as the next phase in their robotaxi development. “We want to either have [autonomous vehicles] not on the city streets at all or very limited,” one Rebel told the Standard. “It's like the state has decided that these things are going to be deployed in San Francisco without the consent of the city or the people in it.”

An unnamed Waymo spokesperson called the coning “vandalism” that “encourages unsafe and disrespectful behavior on our roadways.” Hannah Lindow, a Cruise spokesperson who was at least brave enough to attach her name to her statement, told the Standard that “intentionally obstructing vehicles gets in the way of those efforts and risks creating traffic congestion for local residents.” The SFMTA, San Francisco’s municipal transport agency, said on Twitter Friday that it “does not endorse ANY actions that may increase the number of disabled AVs on San Francisco streets,” and encouraged people to attend this week’s CPUC meeting.

⚡️ Want to attend the big CPUC vote on AVs? Here are the details: ⚡️

When: Thursday July 13, 11am PT

Where: CPUC Auditorium, 505 Van Ness Ave., San Francisco, CA 94102; also available via webcast or phone

Dial in: (800) 857-1917, passcode: 9899501#

Autonomous vehicles are one of our era’s defining moonshots. Silicon Valley and the auto industry—companies from Google to GM, Ford to Zoox—have collectively sunk more than $100 billion into developing vehicles that can navigate everything from endless highways to complex urban grids in all sorts of weather conditions, with the ultimate aim of getting human drivers off the road. Driverless disciples believe the technology will eliminate road fatalities, decrease congestion, and spell the end of those sprawling, oppressive parking lots. They also plan for it to make a lot of money—which, more than $100 billion in, they definitely need it to.

The AV industry as your average consumer relates to it has been developing along a two-pronged track. First is the incorporation of “driver assist” technologies in consumer-grade vehicles. These range from fairly mundane features like cruise control and blind-spot detection, to the controversial Tesla “autopilot” system. The second pathway to driverlessness is through robotaxis. Companies like Waymo and Cruise are designing fleets of AVs that will be able to provide an Uber-like service without a human behind the steering wheel. The vision once again is unfettered profits. The economics of ride-hail are tricky, but eliminating human labor from the equation could make them much more attractive. As Uber co-founder Travis Kalanick told the world at a conference nearly 10 years ago in his signature unapologetic style, “The reason Uber could be expensive is you’re paying for the other dude in the car.”

The other thing about driverless cars is that they are always five years away. It turns out this stuff is really complicated, and even $100 billion and the most powerful egos in Silicon Valley haven’t been able to get it done as fast as they hoped. There are practical problems, there are regulatory problems, there are ethical problems. There are people, the biggest problem of all. People, they are so unpredictable! Some are bad drivers. Some are possibly deranged. Some are central-casting villains whose ill-conceived heists waste so much time and money and credibility. Some refuse to drink the Silicon Valley kool-aid altogether, are opposed to our driverless future, and are willing to make that point with a strategically placed traffic cone.

There is a long tradition in urbanism of residents taking matters into their own hands when they feel abandoned by local authorities. It is known variously in the academic literature as tactical, do-it-yourself (DIY), pop-up, and even guerilla urbanism. Examples of tactical urbanism include turning dumpsters into swimming pools, reclaiming parking spots as tiny parks, and painting crosswalks on neglected intersections. These interventions have been described as playful, innovative, and spontaneous. They are typically low budget and executed by volunteers or activists. All are by definition unsanctioned.

Using traffic cones to disarm a driverless car is textbook tactical urbanism: an intervention by concerned local activists in response to perceived neglect and inaction by local authorities. It’s also brilliant. I challenge you to find a more powerful image of people protesting technology in the recent past than that of the humble orange traffic cone perched atop an inert driverless car. There is the obvious metaphor (a Silicon Valley unicorn, rendered literal and impotent), the terrific color and contrast, the clear juxtaposition of power and wealth with human ingenuity. The financials, should you pause to consider them, are mind-blowing. You can buy a dozen heavy-duty traffic cones on Amazon for about $250, or about $21 per cone. You can use that $21 object to incapacitate a machine that has so far cost many billions of dollars to develop, and will surely consume many billions more.

It is hard to imagine a more effective public awareness campaign for the forthcoming CPUC meeting than the “Week of Cone,” as Safe Street Rebel dubbed it. A vote that had threatened to slip by quietly is suddenly the subject of both traditional press and viral social media chatter. It’s possible nothing changes; it’s also possible that people turn out in force on Thursday to have their say on the future of AVs in San Francisco. This, more than flashy stunts, is the essence of tactical urbanism: using creative, unofficial, rebellious tactics to inspire people to engage as stakeholders in their communities and urban landscapes; reminding us to exercise our participatory power even as corporations threaten to buy it up and take it away.

The broader issue involved in the AV debate is "preemption;" i.e. statutes that give states absolute authority over municipal governments in regulating critical aspects of city life. For obvious reasons, big tech players and TNCs have lobbied heavily to broaden preemption coverage on a number of transportation issues, making it far easier for them to influence only 50 state agencies and legislatures rather than hundreds of city governments.

No wonder some residents of SF feel the need to resort to guerrilla urbanism.

There are merits to both sides of the preemption argument, but a compromise I could support is judicious use of exemptions, where a state's largest cities could opt out of statewide regulation if a majority of city residents support a referendum to do so. There is already a precedent city exemptions in the ridehail market. Seattle took advantage of its exemption from statewide regulation of ridehail operations to pass the most generous pay/benefits law in the US last year. Washington subsequently followed Seattle's lead and passed statewide legislation to enhance driver pay and working conditions for all Washington ridehail drivers.

Given the pervasive impacts robotaxi expansion will have on SF residents and workers, it seems inappropriate that oversight should be goverened by an unelected state commission.