Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy.

If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. This is issue 🎉 one hundred 🎉 published April 17, 2018.

Back in the very first issue of Oversharing in March 2016, I said this newsletter would cover the "sharing" economy, that "ultra-hyped and probably misnamed thing that we know startlingly little about." Today I am delighted to say that, two years later, that description still pretty much holds true. The sharing economy remains hyped, probably misnamed, and a thing that, at least in terms of hard data, we know startlingly little about. Of course, other things have changed a lot. Instacart has stopped struggling, thanks to Amazon buying Whole Foods; WeWork has expanded far beyond offices; and Uber has bigger problems than a regulatory scuffle with 61-year-old Austin councilwoman Ann Kitchen. Frankly, I wasn't sure back then that the sharing economy would still be a going concern in a few years, much less a topic for this newsletter. But here we are! Let's reflect on the things that have kept both sharing and Oversharing in business.

Venture-capital subsidies.

Where would any of us be without the steady drip of money from Silicon Valley investors? There would be no cheap rides, no free food, no free meal kits, no $50 off your first three-hour home-cleaning from Handy. There might also very well be no sharing or gig economy companies, as most of them have relied heavily on funding from venture capitalists to boost worker wages, discount consumer services, and generally invest in growing their businesses.

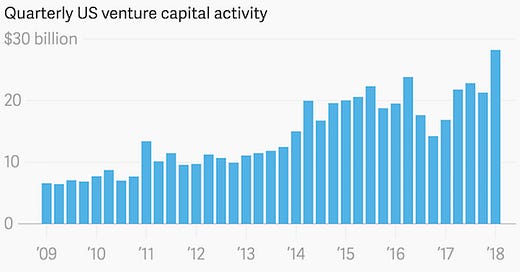

It looked briefly in April 2016 like the "unicorn financing market," as Benchmark's Bill Gurley termed it, may have run its course, but the Wall Street Journal reports that the "Silicon Valley money machine is once again in high gear, thanks largely to SoftBank." The Japanese conglomerate is plowing billions of dollars into startups, sharing economy companies chief among them. SoftBank's investments this year include DoorDash, Lyft, and dog-walking app Wag, all of which, according to the Journal, "have received hundreds of millions of dollars more than they sought." In the first quarter of 2018, US startups raised more than $28 billion, with 41 of those deals worth $100 million or more, according to PitchBook. SoftBank's Q1 investments totaled $3.4 billion, excluding its massive secondary investment into Uber. Even Gurley has changed his tune. "We're encouraging the excessive use of capital," he said at a conference in February, according to the Journal. "We're all doing it because it's the game on the field."

In memorium.

Prim (2013-January 2014)

Homejoy (2012-July 2015)

Caarbon (2014-August 2015)

Vatler (2014-September 2015)

Sidecar (2012-December 2015)

Spoonrocket (2013-March 2016)

Washio (2013-October 2016)

Bento (2015-January 2017)

Maple (2014-May 2017)

Sprig (2013-May 2017)

Shyp (2013-March 2018)

(The correct answer to "where would any of us be without venture capital subsidies?" is "out of business.")

Unresolved legal questions.

Are Uber drivers employees or independent contractors? We still aren't sure! Nine years after the ride-hailing company was founded, courts are still weighing this question, with different results. Last week, for example, a US judge in Philadelphia ruled that limousine drivers for Uber Technologies Inc. are independent contractors under federal law, because Uber doesn't exert enough control for them to be deemed employees. The lawyer for the drivers plans to appeal the ruling to the US 3rd Circuit, which would be the first federal appeals court to ponder whether Uber drivers are contractors or employees.

Courts around the world are divided on this question. New York state in June 2017 found three Uber drivers to be employees for benefits purposes; a British tribunal said in October 2016 and then again in November 2017 that Uber drivers were employees; a French court said this past February an Uber driver wasn't an employee; also that month, a federal judge in California declared Grubhub drivers to be contractors in a landmark ruling for the gig economy.

It is all very confusing and this confusion is precisely what has allowed the "gig" model of hiring workers as contractors to thrive. Companies save as much as 30% on labor costs by hiring contractors; onboarding millions of drivers as independent contractors has enabled Uber's model of having drivers rent or own their cars, pay on-the-job expenses (gas, insurance, depreciation, etc.), and sign on and off the platform as needed instead of working regular shifts. Uber's main expense is already earnings and promotions paid out to drivers, which totaled about $8 billion in the fourth quarter of 2017. Imagine how much higher those costs would be if every driver were also an employee.

"Mobility."

Two years ago when we talked about the future of transportation we talked about Uber and Lyft. Today we talk about mobility, the transit equivalent of an all-inclusive buffet. Mobility is used to describe a future in which the typical consumer doesn't own a car, but rather relies on a combination of shared rides, bicycles, scooters, public transit, and perhaps even flying cars for their daily transportation needs.

One recent trend in mobility is flexible car rentals. Uber last week announced plans to launch Uber Rent, a rental car network managed through a partnership with car-sharing startup Getaround, in San Francisco this month. On Monday (April 16), Turo, another car-sharing startup, expanded its platform to include "commercial" listingsfrom small rental-car companies in 56 countries, and said it had increased its series D funding to $104 million, from $92 million. The general idea is that in a future where many people don't own cars, being able to rent a car for a couple hours or days will be a nice complement to booking a ride on Uber or taking public transit. A car rental, for instance, might be more helpful for running errands or going on a short day trip, while an Uber or the subway is better for commuting between two points.

Elsewhere in mobility, the tenth circle of hell might be scooters, and California isn't having it:

San Francisco’s battle with companies that rent electric scooters kicked into high gear Monday as City Attorney Dennis Herrera issued cease-and-desist orders to the businesses even as the Board of Supervisors was considering a proposal to regulate the divisive transportation devices.

And:

In Santa Monica, home to e-scooter company Bird, the city attorney's office in December filed a criminal complaint against Bird and its founder alleging the company began operating without approval and ignored required licensing and orders to remove the scooters from sidewalks. Bird pleaded no contest and agreed to pay more than $300,000 in fines and secure proper licenses.

And:

The problem is that scooters have flooded streets and sidewalks, and people are leaving them everywhere, creating a mess and nuisance. The cities feel like the fault lies with the scooter companies, and the companies blame it on their users, insisting that they have made clear in the app that riders are to park the vehicles in reasonable, out-of-the-way spots. This latter argument strikes me as similar to leaving a small child alone with a large bag of candy and instructions to eat just one piece, and then later blaming the child for ignoring the instructions and becoming ill by eating the entire bag.

Anyway, here is Hunter Walk of Homebrew arguing for a "safe harbor" approach to urban mobility, whereby startups could test new products "for a limited period of time over a particular density":

Startups would agree to proactively “file notice” of a test and share resulting data with the city. All tests are approved on an opt-out basis. That is, if the public official overseeing the Safe Harbor initiative has concerns, they can block the test but a judge will review the materials and rule within a few business days. The test can stay private for up to 28 days or so, after which the basic information will be made public by the city.

It would probably make the startups happy! Maybe not the cities. To all my San Francisco-based readers: please send in photos of scooter sidewalk chaos. It's stuff like this that really keeps Oversharing going.

Travis Kalanick.

Last but not least, I think we can all agree that Travis has added a lot to this newsletter.

Other stuff.

Waymo applies to test cars without drivers in California. WeWork buys China's Naked Hub for $400 million. WeWork rival Knotel raises $70 million at $500 million valuation. Tentrr gets $8 million for private glamping rentals. Checkr raises $100 million for background checks. Judge weighs Uber's $10 million sexual harassment settlement. Tech startup Slice helps local pizzerias compete with Domino's. Walmart partners with Postmates on grocery delivery. Publix expands curbside pickup. Ride-hailing companies sue New York City over accessibility requirements. Ola Wants a Million Electric Rides on India's Roads by 2021. Lyft would love to be in Japan. World's First Electrified Road for Charging Vehicles Opens in Sweden. TaskRabbit investigating cybersecurity incident. Teachers struggle with second jobs. Bexar County approves $49,000 contract with Lyft. Pittsburgh Lyft riders tip very well. What Lyft says drivers actually make. Silicon Valley prepares for IPO wave. "Humans are underrated."

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and ideas for the next 100 issues to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.