Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy.

If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. This is issue 101, published April 24, 2018.

Going to the prom.

Didi Chuxing could IPO as soon as this year:

The Beijing-based company has in recent weeks been in talks with bankers about the feasibility of tapping the public markets for cash in the second half of 2018, as it looks to amass a large war chest to fend off rivals in China and other countries, the people said.

Didi—which operates China’s largest ride-sharing platform and is expanding in Latin America and other parts of Asia—is hoping to fetch a valuation of at least $70 billion to $80 billion if it goes public, one of the people added.

A 2018 IPO would put Didi well ahead of Uber, which under co-founder and former chief executive Travis Kalanick planned to go public "as late as humanly possible," and which under resident fixer and grown-up Dara Khosrowshahi is targeting a debut in 2019.

Didi is at the center of the ride-hailing web that SoftBank has spun. It's invested in Lyft, Uber through the deal they cut in August 2016, Southeast Asia's Grab, India's Ola, and the Middle East's Careem. It put $100 million into and later acquired Brazil's 99. SoftBank has also invested in most of these companies and could help broker truces and alliances between regional players, like Uber's recent sale of its Southeast Asia operations to Grab. SoftBank is playing the ride-hailing version of Risk, but it also owns all the players. So long as a single company controls a country or region, so that it's not burning money on competition, SoftBank seems likely to be happy with the outcome.

That said, insofar as SoftBank has picked a single winner, it seems like Didi. It's notable that Didi has continued to expand globally even as Uber has now repeatedly withdrawn from key international markets. In its latest move, Didi said Monday (April 23) that it would launch in Mexico, intensifying its battle with Uber for Latin America. Didi is recruiting drivers until mid-June with a zero commission model (i.e., the drivers keep all the money) and after that says it will take 20% of the fare compared to Uber's 25%. Latin America is one of Uber's strongest and least contested markets, making a challenge from Didi extra unwelcome.

While it's much too soon to know what will happen, the notion that SoftBank has picked Didi as its favorite should be deeply troubling to Uber. If Didi and its affiliates (Grab, Ola, Careem, 99) lock up most of Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, Uber would be left with Australia, the US, and Europe. There will always be plenty of competition in the US from Lyft, other ride-hailing startups, and automakers, and Europe from the company's perspective is a mess of regulations and worker protections. Simply put, they are not the markets you would pick to build the biggest and most profitable business. In that scenario, Uber's stakes in Grab and Didi might be what it really relies on to cash in.

Housing effects.

A common critique of Airbnb is that it's intensifying housing crises in cities that already don't have many rooms to spare. This has been a chief worry of places like San Francisco, New York, and Berlin in passing tougher rules around people who rent out their homes to visitors for so-called short-term rentals. Bloomberg View's Noah Smith is unconvinced:

It’s hard to measure how big Airbnb’s impact really is, though. McGill University urban planning professor David Wachsmuth recently looked at New York and concluded that Airbnb listings were rising in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods such as Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, where rents have also been skyrocketing. But this could mostly be a coincidence -- travelers may enjoy staying in hip, up-and-coming neighborhoods, or new urban pioneers may start offering Airbnb rentals as they move in.

He cites a recent paper from three economists that finds the "true impact" of Airbnb on rents is just a 0.018% increase for every 1% increase in Airbnb listings. Here's Smith:

That’s a minuscule effect. It means that doubling the number of Airbnb listings would raise rent by less than 2 percent overall. The effect is so small that in their presentation at the American Economic Association meeting in January, the authors referred to it as a “zero effect on rental rates” overall (though the effect isn’t necessarily zero in all areas).

One reason the paper's authors argue the real effect on rent is so small is because most short-term renters on Airbnb and similar platforms are offering up their own homes. This aligns nicely with the logic Airbnb has pivoted to in recent years, since it decided to play nice with cities instead of fighting every regulation tooth-and-nail. The company now promotes a "one host, one home" policy in housing-constrained places like San Francisco and New York that limits its hosts to listing their primary residence, and has purged many of the "illegal hoteliers" that were running fly-by-night commercial operations. As of April, for example, Airbnb claimed that 95% of its hosts in New York had only one listing

The paper argues that local regulations should "seek to limit the reallocation of housing stock from long-term rentals to short-term rentals, without discouraging the use of home-sharing by owner occupiers." It suggests this could be accomplished by charging occupancy tax only on hosts "who rent the entire home for an extended period of time" or, alternatively, by allowing hosts to waive the tax by providing "a proof of owner-occupancy." Smith is interested in taking this model a step further:

…given the benefits for travelers, a smarter approach might be to allow commercial Airbnb operation but to tax and regulate it like the hotel industry. Buildings that allow commercial Airbnb operations could be required to advertise this fact to potential tenants, and commercial Airbnb operators could be required to follow cleaning and safety procedures similar to those used by bed and breakfasts. Finally, a tax could be applied to commercial Airbnb operation, with the proceeds used to fund affordable housing.

It's an interesting idea, though one that all the relevant parties would probably hate. Hotels would hate it for further legitimizing Airbnb's operations, and green-lighting their way into a somewhat more traditional hotel business. Tenants who already oppose Airbnb would hate seeing their landlords convert residential buildings into "commercial" Airbnb units with tourists traipsing through day and night. I have faith that affordable housing advocates would find something to hate about it, too.

Growing up.

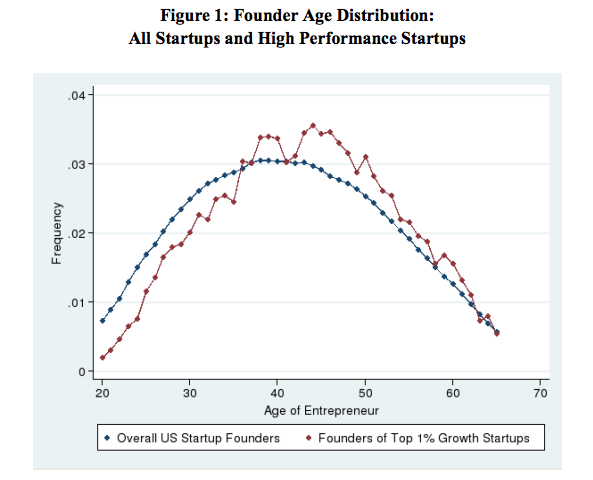

The tech bros aren't as young as you thought. According to a recent working paper, "Age and High-Growth Entrepreneurship," from researchers at MIT, Northwestern's Kellogg School of Management, and the US Census Bureau, the "mean founder age" is actually 42, and for the top 0.1% of startups, it's 45.

The stereotypical startup founder is, of course, a 20- or 30-something man, probably white, probably wealthy, who acts as though he's still in college. He wears a fleece vest, rides electric scooters, and drinks Blue Bottle coffee. The introduction to the paper is admirably devoted to this trope (minus the vests, scooters, and coffee). It begins with a quote from Mark Zuckerberg, "young people are just smarter," moves on to Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, and ends at Peter Thiel, who grants $100,000 fellowships to people younger than 23 if they "stop out" of school. Previous research has put the mean founder age at about 30.

What these narratives leave out is that young startup founders also have all sorts of disadvantages. They know fewer people, which can make it harder to get funding. They have less experience and fewer specialties. They often run into problems when it comes to hiring and having to actually manage a company.

The paper combines data from the IRS and Census with information from the USPTO and third-party research on venture capital. "Our primary finding is that successful entrepreneurs are middle-aged, not young," the authors write. "We find no evidence to suggest that founders in their 20s are especially likely to succeed. Rather, all evidence points to founders being especially successful when starting businesses in middle age or beyond, while young founders appear disadvantaged."

Previous research has found that past success predicts future success in entrepreneurship. "Age and High Growth Entrepreneurship" finds not only that older startup founders perform better, but that "younger founders appear strongly disadvantaged in their tendency to produce the highest-growth companies."

Why then the persistent myth of the startup wunderkind? Young people are generally considered more creative and more open to taking risks. That pairs well with the Silicon Valley mantra of "move fast and break things." The paper theorizes that VCs might also prefer to bet on young people, who are more likely to need early stage financing and might be less savvy in negotiating their financing deals. They also make for better stories. People love to read about the nerdy kid who built a multibillion-dollar company in his dorm room or the young Tinder founder who was ousted and sought a comeback. Travis Kalanick wasn't under 30, but his bro-y swagger and frat-boy attitude elevated him to microcelebrity. These people are natural characters. Imagine the Social Network without the angsty music and brooding shots of Harvard final clubs. It would be a much worse movie.

Pop the trunk.

Have you ever been like, hey, I really wish Amazon would leave that package I ordered in my car trunk? Good news, now they can! Amazon said today that millions of Prime members could use Amazon Key—a service that works through an app with internet-connected cars—to have deliveries placed inside their Chevrolet, Buick, GMC, Cadillac, or Volvo vehicle. The Amazon Key app notifies customers when deliveries are en route, and once packages have been dropped off, which is basically the same as USPS, except the part about it going into your car trunk.

The next wave in on-demand everything is to create more spots where companies that exist mainly online can deposit your physical goods. Amazon is working on this car delivery option, bought Whole Foods and its network of more than 400 stores, and has beefed up its Amazon Locker program. Walmart wants to deliver groceries directly into your fridge. One question about trunk deliveries is whether they'd be any better for perishable groceries (it seems like most likely not).

Outside of car trunks, last-mile delivery remains big, if not exactly profitable, business. Walmart struck a deal with DoorDash to power grocery delivery in Atlanta. The service is not exactly white label, as DoorDash workers will still "often wear the DoorDash shirt and have the DoorDash bag," DoorDash chief operating officer Christopher Payne tells TechCrunch. Walmart seems like it's really playing the field here, as it also recently started testing grocery delivery with Postmates in Charlotte, North Carolina. It previously tried out Uber in Phoenix, Lyft in Denver, and Deliv for orders from Sam's Club in Miami.

Elsewhere, Postmates will now deliver to predominantly black neighborhoods on the east of the Anacostia River in Washington DC after the Washington Post highlighted the lack of food delivery services in the area.

Other stuff.

SquareFoot raises $7 million for office brokerage. Square acquires catering startup Zesty. Amazon's other Jeff. Uber eyes VMware's Zane Rowe for CFO job. UberEats breaks away from food delivery competitors. All the Otto co-founders have left Uber. Bill Gurley is back on team Uber. Tesla, Waymo race for self-driving car data. Lyft pledges rides will be carbon neutral. Careem says hackers stole data of 14 million riders and drivers. Aleksandr Kogan says he's not a Russian spy. Uber Denies Its CTO Met With Cambridge Analytica. UberEats draws scrutiny in Australia. Judge dismisses most of Uber "Hell" spying suit. MealPal talks low margins. Autonomous Boats Will Be on the Market Sooner Than Self-Driving Cars. Japan tightens rules on home-sharing. Spanish resort city Palma to ban holiday rentals. Airbnb for luggage storage. Uber for lawn care. Uber baby. Rebranded Chinese scooters are taking over San Francisco. "I don't know who comes up with these ideas or where these people come from." "I never just throw a party. I am knee-deep. I roll up my sleeves."

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and startup wunderkinds to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.