The real unicorn is a profitable ride-hail company

CXCII

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

Last week I asked that if you like this newsletter you kindly consider hitting the like button, and then the like button broke, which was honestly pretty funny, this time the joke was on me. So let’s try that again! If you like Oversharing, please click the small gray heart at the top or bottom of the email. Teamwork makes the dream work.

Driving profits.

Madrid-based Cabify may be the true unicorn of the ride-hail space. Cabify says it made a small profit of $3 million in earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization in the fourth quarter of 2019, the Financial Times reported.

Yes, we’re talking a real, if small, EBITDA profit. This isn’t community-adjusted, “profitable profitable,” “on the precipice of being profitable,” or EEG (that would be earnings excluding gluten, a Quartz-exclusive accounting term). Good old-fashioned EBITDA! Who knew any startup still used it.

Here is more from the FT:

Cabify reported net sales of $29m for the quarter and $104m for 2019 as a whole, from a total of $708m in rides. It added that its turn towards profitability was largely because of technology that allowed it to use discounts and subsidies more effectively.

It said that operating free cash flow, which factors in some payments to engineers, was also positive or about break even.

“The business as it is now can sustain itself and survive,” Juan de Antonio, the founder and chief executive of the group, said in an interview. “What is happening in the rest of our industry is very different . . . is a unique achievement.”

You hear all sorts of theories about how ride-hail companies might one day reach profitability—ditching labor costs with driverless cars, locking in revenue with subscriptions, diversifying into food delivery—but the real answer always seems to be quitting the subsidies these companies are so addicted to.

One company definitely not slowing down on incentives is India’s Ola, which launched yesterday in London. Ola has SoftBank money—honestly, who doesn’t—and is spending it in style for its London debut. When I downloaded the app yesterday, Ola gave me £5 for signing up, £5 for adding a debit/credit card, and promised two more £5 ride vouchers when I take my first ride. I could get another £5 by setting up a second payment method (Apple Pay, prepaid card). All told, Ola was prepared to throw £25 at me just for setting up the app, not to mention £10 per friend I referred.

Anyway, it turns out you can also save a lot of money when you stop giving away so much of it. Cabify seems to have figured this out. Longtime-discount-king Uber is realizing it too. “We’re making proactive changes to achieve significant cost leverage for both Ride and Eats,” Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said on the company’s fourth-quarter earnings call last week, citing better targeting of incentives and online marketing as one example. “In the past month or so, we’ve seen Lyft, our competitor, probably be on balance more aggressive in terms of discounting and incentives,” he added later. “We’ll see where that leads.”

Unlike Cabify, Uber had no profit to show for the fourth quarter. It booked a $1.1 billion loss for the period, and an $8.5 billion loss for the full year thanks to hefty stock-based compensation expenses. For context, that means Uber lost more than WeWork is now worth in 2019. Despite that, Uber also pushed up its profitability target from full year 2021 to the fourth quarter of 2020. That’s right: Uber is, dare I say, on the precipice of being profitable.

Brandless™️.

Once there was a company called Brandless whose whole thing was to have a distinctly brand-free brand. “We’re not anti-brand, we’re not not a brand, we’re just reimagining what it means to be a brand,” co-founder and CEO Tina Sharkey said. Brandless launched selling stuff like hand soap and apple cider vinegar and organic taco seasoning mix for the flat price of $3 each. It was consumer-packaged goods for the “conscious urban millennial.” Everything came with a minimalist label in pastel colors and sans-serif font. You could have peeled them off and stuck them on the walls of the subway to blend in with all the other startup ads.

You know who was into the vision of reimagining what it means to be a brand? Yep, it was the SoftBank Vision Fund. Brandless’s $3 price point reportedly flabbergasted SoftBank chief Masayoshi Son, and in July 2018 SoftBank led a $240 million round in the company that was said to value it at $500 million.

The Information later reported that SoftBank had put in $200 million of the round, to be paid in installments. As of last summer, cracks were beginning to show. Brandless laid off employees and Sharkey stepped down. The Information also reported that SoftBank had given Brandless only the first half of its investment, and was threatening to withhold the other $100 million unless Brandless started to hit financial targets.

Long story short, the vision did not pan out:

Today direct-to-consumer retailer Brandless becomes the first SoftBank Vision Fund-backed startup to close down, as it stops taking orders and halts all business operations. The company will be laying off 70 people, or nearly 90% of its staff, according to a company spokesperson. The last 10 employees will stay to finish the remaining customer orders and evaluate any acquisition offers.

Brandless' closure marks the end of a turbulent, short run that began 2.5 years ago and was beset with a challenging business model from the start. In a statement, the company blamed a "fiercely competitive" retail market that was "unsustainable" for its business.

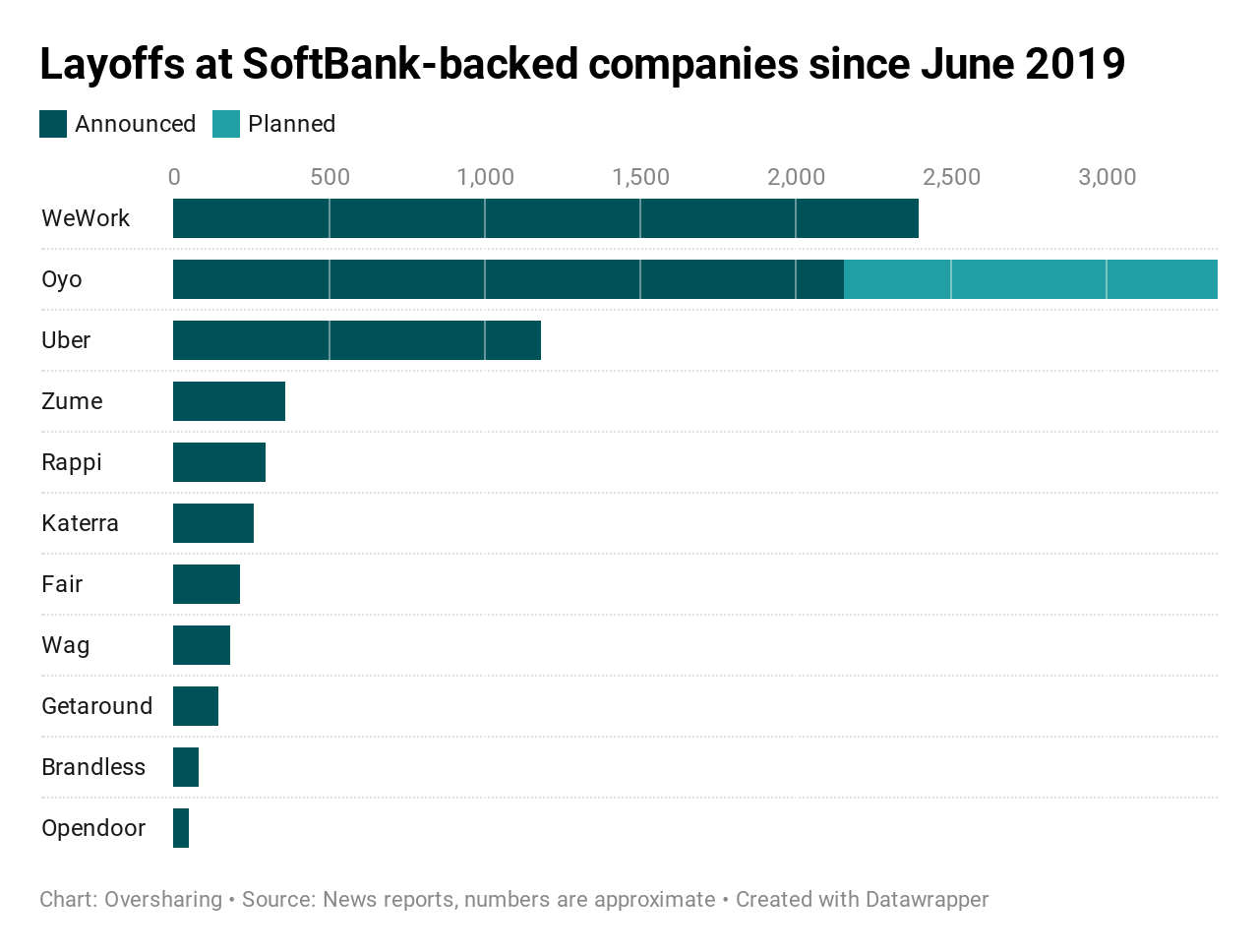

The additional 70 layoffs at Brandless, combined with around 360 job cuts last month at Indian hotel chain Oyo in the US, bring the total layoffs at SoftBank portfolio companies to over 3,000 this year, and over 7,300 since June 2019.

Scooters!

Scooter operators have fled Atlanta, Georgia, since the city implemented a nighttime ban on electric-scooter and -bike rides last summer. Gotcha, Lyft, Lime, and Bolt have all pulled operations from Atlanta in the months since the ban took effect, while Bird, Uber-owned Jump (scooters, not e-bikes), Wheels, and Boaz are still operating, the city said.

Atlanta banned riding e-scooters and e-bikes from 9pm to 4am on Aug. 8, 2019, after four scooter riders died in motor vehicle collisions over the summer. At least 29 people have died in scooter crashes since companies like Bird and Lime popularized them in 2018, according to reports I tracked in the global media. (A separate count shared by Twitter user @Asher after my story puts that number closer to 60.)

The four deaths in Atlanta are the most in any single city, by my tally. Atlanta says it hasn’t had a death since the nighttime ban took effect. That should be good news, but the curfew itself has been controversial and unpopular among scooter firms. When Lime pulled out of Atlanta, a spokesperson told Curbed that new laws on e-bike and e-scooters weren’t conducive to a profitable environment.

The effect of the rules is most obvious in 2019 trip data Atlanta released recently, which shows the number of monthly e-bike and e-scooter trips peaking in July 2019 and plummeting sharply after that. Some of the drop is probably seasonality—scooters are less popular in the winter—but weather alone seems unlikely to explain the depth of the decline, with trips in December down more than 60% from trips in February. Limited hours and fewer scooter operators are more likely culprits.

Wake-up call.

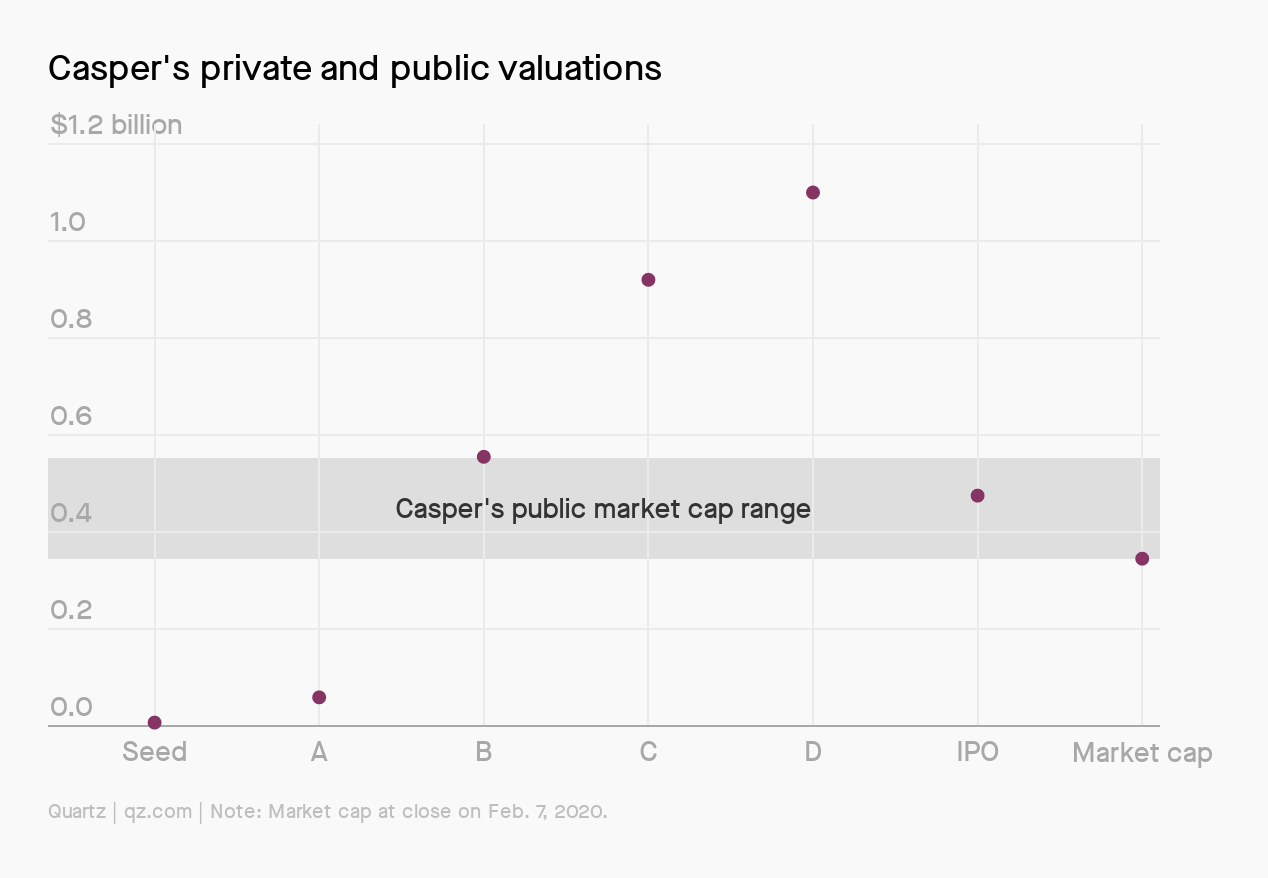

Casper Sleep Inc., a self-described “pioneer of the Sleep Economy,” was a unicorn to private investors. To the public markets, it is only about a third of one. After pricing shares at $12, the low end of a range it had already cut, Casper gained 12.5% on its first day of trading, then fell 18% on its second.

Selling mattresses is not a technology business, but Casper was clever. It wrapped itself in the trappings of tech startupdom—data, an app, subway codes, podcast ads!—and used that to raise tech-startup money at tech-startup valuations. Casper raised more than $300 million at a valuation of over $1 billion, a bona fide startup unicorn.

What is Casper, if not a tech firm? It’s a sleek, direct-to-consumer company that realized buying a mattress is an awful experience that could be made a little less awful with online purchases, free delivery, and free trials. It’s a middleman that sources its mattresses from a small number of manufacturers, at least one of whom also makes mattresses for Casper’s many competitors.

Casper did resemble a tech startup in one crucial way: its losses. Casper lost money in every quarter it disclosed results for in its IPO prospectus. In the first three quarters of 2019, Casper lost $67 million on $312 million in revenue.

Selling private investors on big dreams and bigger losses was the model du jour for much of the past decade, boosting companies like Uber, Lyft, Postmates, DoorDash, and WeWork. Any of these companies could arguably be better classified as something other than tech: transportation, logistics, real estate. But venture firms had capital to deploy, and they wanted to put it in tech companies, not a logistics firm with an app.

What became clear last year, as Uber and Lyft went public, and WeWork aborted, was that public markets largely weren’t buying the stories these companies and their private investors told. In retrospect, it’s worth asking whether private investors believed them, or simply thought someone else would.

This time last year.

DoorDash is the dark horse in the food delivery race

Other stuff.

Inside the SoftBank Vision Fund’s Civil War. Brazilian higher court rules Uber drivers not employees. The Local Regulations That Can Kill E-Scooters. Spanish mobility startup Cooltra asked to pull 1,200 e-mopeds from Barcelona. How Finland cycles through the winter. Schick owner ditches Harry’s takeover after FTC sues to block deal. Judge denies Uber’s, Postmates’ request to block AB5 from taking effect. Morgan Stanley marketing 6.3 million-share stake in Uber. Cities are using micromobility data to solve transit problems. “We were all happy about this idea of not losing our jobs in two years.” Justice Department ramps up Google probe. FTC to examine past acquisitions by big tech companies. Russia’s Google Will Bring You Groceries in Just 15 Minutes. $100 billion Mormon church fund was the best-kept secret in the investment world.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and Brandless labels to @alisongriswold, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.