Before we start, I wanted to offer a caption contest. I am never one pass up a good metaphor, and there is an incredible one hiding in this image of a unicorn taiyaki. Submit ideas to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.

Reputational losses.

"There is a high cost to a bad reputation," Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi wrote to staff in a memo late last month. How high? NYU professor Scott Galloway says $20 billion to $30 billion.

"Uber's probably been the best lesson in poor corporate governance and how it can destroy tens of billions of dollars in shareholder value," Galloway tells Business Insider. "You could argue that poor corporate governance here and the inability to step in and make hard decisions probably cost that company ten or twenty billion dollars."

I won't bore you with the long list of things Uber did this year and in years prior to build that bad reputation. In the meantime, here is Bloomberg's Eric Newcomer on the five criminal probes Uber faces in the US:

Uber faces at least five criminal probes from the Justice Department—two more than previously reported. Bloomberg has learned that authorities are asking questions about whether Uber violated price-transparency laws, and officials are separately looking into the company’s role in the alleged theft of schematics and other documents outlining Alphabet Inc.’s autonomous-driving technology. Uber is also defending itself against dozens of civil suits, including one brought by Alphabet that’s scheduled to go to trial in December.

And here is media mogul and Uber board member Arianna Huffington saying Uber's problem "was this worship at the altar of hyper growth."

More people in fewer cars.

Uber likes to talk about putting "more people in fewer cars." That was literally the title of a Ted Talk that Travis Kalanick gave in Vancouver in February 2016, you know, the good old days when he was still Uber's chief executive and the company wasn't facing five criminal inquiries. The talk is about UberPool, the shared rides service that Uber introduced in Los Angeles in mid 2015. "Since then, we've taken 7.9 million miles off the roads and we've taken 1.4 thousand metric tons of CO2 out of the air," Travis says, to applause. "But my favorite statistic… is that eight months later, we have added 100,000 new people that are carpooling every week."

Uber's math on Pool has always implied that each additional rider takes "miles off the road" because Pool, a shared ride, substitutes for a trip they would otherwise take in a personal vehicle. But what if that's not the case? What if ride-hailing services aren't really putting "more people in fewer cars," but "more people in more cars"?

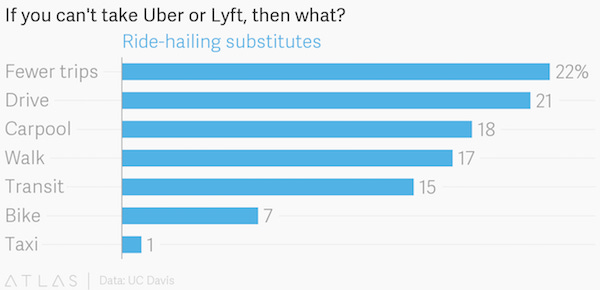

That's the crux of a new study from UC Davis, which finds that "substantial policy action may be required to ensure that ride-hailing can effectively be woven into the transportation network while reducing congestion and the emissions of transportation services." Specifically, the study is concerned that ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft aren't just reducing trips in cars, but also trips on public transit, by bike, and on foot. The study finds that ride-hailing decreases use of public transit systems in major US cities by an average of 6%. It also finds that if Uber and Lyft were unavailable 49% to 61% of ride-hailing trips would have been made by walking, biking, public transit, or not taken at all.

When the study came out last week, people seemed surprised by this, but why? There have always been two main considerations with UberPool and Lyft Line. The first is that they get people to share rides. The second is that they make car rides a whole lot cheaper, which encourages more people to take them.

Put another way, Uber and Lyft might want to put more people in fewer cars, but they also want to do more trips. They've accomplished this by making Pool and Line almost unfathomably cheap, an effect that, as Uber well knows, is sure to increase rider demand and require a corresponding increase in driver supply. In New York City, for example, Uber has deployed tens of thousands of black cars and in July finally recorded more trips per day than taxis. In San Francisco, transit officials believe the estimated 45,000 Uber and Lyft drivers are worsening traffic and increasing carbon emissions. San Francisco mayor Ed Lee in May demanded Uber share more information on its trips, while the city attorney's office sued Uber to compel it to give up records.

Could Uber and Lyft reduce vehicle miles with shared rides services? Sure. Will they, so long as taking Pool or Line is cheaper and more convenient than taking public transit, biking, or walking? Probably not. For ride-"sharing" to reduce congestion, it needs to appear more attractive than a private ride but not so much as a non-car option that produces even less traffic and emissions. Right now, it seems better than both.

I love Big Macs.

Crowdtap is a crowd-based platform that encourages regular people ("members") to promote brands ("complete missions") on social media ("by creating top quality content") in exchange for free stuff ("gift cards, product samples, and other rewards"). People on Crowdtap love free stuff. They love Marc Jacob eye highliner, Splenda zero liquid, and Domino quick dissolve sugar. Crowdtap loves connecting them with brands. "Crowdtap partners with great brands to offer members opportunities to provide feedback, be creative, and get rewards & free sampling," the company says on its website.

Ah but then it gets weird:

These people don't have large social media followings (in fact, Crowdtap users I interviewed said they create throwaway social media accounts to use exclusively for Crowdtap). And sharing content on social media isn't even required—the default option is to share, but you get your points either way. Crowdtap passes members' responses on to brands, but otherwise nobody is listening to what they say. No one is responding. There's very little about this that might be called social. Imagine someone wandering alone in a giant desert, shouting "I love Big Macs!" into the sky. That's Crowdtap.

That is from this story, written by Daniel Carter, a researcher who studies work. In summer 2016, Carter interviewed 12 people who use Crowdtap and platforms like it. Seven said they were stay-at-home moms, two retired, one disabled, and two said they had disabled children. They typically spend 15 hours a week on Crowdtap and, based on the value of the gift cards and samples they receive, earn an average $2.45 an hour. But Carter thinks the real goal of Crowdtap isn't even to get these people to promote brands to other people. It's to sell stuff to them, to indocrinate them into the habits of being a good modern consumer.

Crowdtap is almost like a form of welfare—be a good consumer, and coupons, tampons, and dog food will trickle down from the sky. In Crowdtap's world, you're not even "working" for your benefits. You're just trudging through the day's list of missions and learning what to spend that $5 gift card on.

When the robots take our jobs, Crowdtap is all we'll have left.

Say you're just a friend.

Airbnb is largely illegal in New York these days, so obviously there is a hipster black market for it in Brooklyn:

Some hosts instruct customers to outright lie about their stays, claiming they're for every reason except the real ones so they don't get busted, Weisberg said.

"We ask our guests not to mention Airbnb because [its company execs] are working on their image," one renter instructed, according to Weisberg.

Another host allegedly said, "Not all buildings in New York are Airbnb-friendly, so we ask that you kindly not mention Airbnb in or around the building."

Weisberg is Herman Weisberg, a former NYPD cop whose investigative firm was hired by the Hotel Association of New York to probe "illegal hotel" activity on Airbnb and similar platforms. The city has ramped up its enforcement of short-term rental laws this year, which forbid renting out a home for less than 30 days unless the host is also present and there are only one or two guests. Enforcement tactics include sheriffs, tickets for violating obscure building codes, and undercover stings by private investigators.

Lying about Airbnb isn't exactly new. BuzzFeed's Caroline O'Donovan reported last year on Airbnb hosts instructing their guests not to mention the home-sharing site to neighbors or building staff. Among other things, listings told prospective guests to use the term "house guest" or say they were staying in a friend's apartment, and to "please do not book if this is a problem."

Elsewhere in Airbnb, the company has partnered with Miami-based Newgard Development Group to construct a 324-unit building in Kissimmee, Florida, designed specifically for Airbnb. The complex, "Niido Powered by Airbnb," will include units with keyless entry (to simplify Airbnb check-ins) and shared common spaces (to give people a place to hang out). Tenants will sign annual leases and be able to rent their rooms or entire units through Airbnb for up to 180 nights a year. Landlords will get a cut of the Airbnb revenue.

Airbnb, of course, does not "own, create, sell, resell, provide, control, manage, offer, deliver, or supply any Listings or Host Services," because in the "sharing" economy having your own assets is criminally uncool. It is getting into the real estate business all the same.

Other stuff.

Uber-for-dog-walking comes under scrutiny. Lyft partners with Chance the Rapper. Uber and Deliveroo grilled on "gig" economy rights. Uber testing system to stop UK drivers from working excessive hours. WeWork Founder Says We've Lost Community. How Old Trolley Technology Is Powering the Trucks of Tomorrow. Whole Foods closes "365" store. What Amazon bookstores suggest about Whole Foods's future. Apoorva Mehta calls Amazon's Whole Foods purchase a "blessing in disguise" for Instacart. Uber Backs Down on Threat to Leave Quebec. Uber appeals ban in London. Uber loses European policy chief. Uber delays opening for San Francisco Mission Bay headquarters. Facebook heads into food delivery. Vacasa raises $104 million in series B funding. Airbnb plans expansion via affiliate program. Lyft makes Google Maps its default navigation tool. Lyft hits half a billion rides. Why investors are betting on bike share. GM's Cruise Automation applies for autonomous vehicle tests in New York. Toyota to test self-driving cars in 2020. Self-Driving Cars Are on a Collision Course With Our Crappy Cities. Black lawmakers to press Silicon Valley on diversity.