The big favor that inflation did for Uber

Rising prices in the global economy provided the perfect cover to raise prices in ride-hail

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the sharing economy. If you’re returning from last time, thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you!

Once again it’s earnings season in the gig economy. Uber and Airbnb kicked things off Tuesday with their Q3 results; a bunch more companies report next week. A quick rundown of the schedule:

Nov. 1: Uber, Airbnb

Nov. 3: DoorDash

Nov. 7: Lyft, Rover

Nov. 9: Fiverr

Nov. 10: Wag!, WeWork

Nov. 14: Bird

TBA: Helbiz

Earnings season in the gig economy also means earnings season in Oversharing. First up: Uber.

For the third quarter, ended Sept. 30, Uber Technologies Inc. reported $29.1 billion in gross bookings (+26% from the same period last year), 124 million monthly active platform consumers (MAPCs, or the number of unique consumers who completed a transaction on Uber’s platform at least once in a given month, +14%), $8.3 billion in revenue (+72%), a net loss of $1.2 billion (half the $2.4 billion net loss from Q3 2021), and $516 million in adjusted ebitda.

The takeaway from all those numbers is that Uber had a good quarter. Revenue and adjusted ebitda beat estimates, and Uber forecast Q4 adjusted ebitda of $600 million to $630 million, also above expectations. Sure, Uber racked up another billion-ish of net loss, largely on revaluations of its equity investments, bringing total net income since it started publicly reporting those figures in 2017 to -$28.5 billion, an absolute value greater than the market cap of HP, Dell, or Barclays. But what to do with such losses at this point other than ¯\_(ツ)_/¯? The market certainly did. Uber’s share price jumped 12% on Tuesday to $29.75, its best showing since late September.

It might be surprising to see Uber, a service that could be considered discretionary spending, having a breakout quarter amid runaway inflation and serious economic anxiety about everything from the price of food to the price of gas. But as CEO Dara Khosrowshahi admitted after the second quarter: inflation has been good for business. Inflation is bringing more drivers to Uber’s platform as they look for ways to top up their earnings and putting the screws to Uber’s more capital-constrained competitors, while also so far failing to put a dent in Uber’s revenues or bookings.

But inflation has done Uber an even bigger favor. It’s provided the perfect cover for raising prices to a new and much higher normal.

Analysts failed to inquire closely about pricing on the investor call on Tuesday, but thankfully we also have journalists. In a Bloomberg Technology TV interview with Khosrowshahi, host Emily Chang pointed out that ride prices are still elevated and asked: “When are prices going to fully come back down? Will they ever really come back down to where they were?”

Uber’s CEO replied (emphasis added):

Well, I do think that inflation has affected everybody, and I think has re-baselined, to some extent, prices. So, I don’t think that prices are going to go down to pre-pandemic levels, but we have seen pricing ease. For example, Q3 pricing versus Q2 pricing—surge levels came down; our average ETAs in terms of, you know, when you push a button, when do you get your car, that’s improved as well; service quality levels have improved.

So we’re hoping that pricing continues to ease going into Q4 and next year, but I do think that this is a new baseline. And, you know, our consumers, our riders, our eaters—they’re willing to pay, as you can see from the growth rates that we’ve seen, as it relates to both audience up 14%, trips up 19%, and then obviously gross bookings, which are dollars in the bank so to speak, up 32%.

There you have it! Prices have gone up, they’re unlikely to come back down, and consumers are still “willing to pay.” This is the new Uber normal. It’s also a sign that upfront pricing—a dynamic pricing algorithm that charges individual customers their willingness to pay using a variety of information Uber has on them and their trip, also known as sophisticated price discrimination—is finally paying dividends.

This admission of a new pricing baseline is a big deal. It wasn’t any secret that Uber’s prices had gone up—anyone who’s taken an Uber lately could tell you that, and analysis from YipitData found that the average price of an UberX or Lyft ride jumped 40% from May 2019 to May 2022—but the question remained was whether this rise was temporary or permanent.

There are various reasons why prices rose during the pandemic. Uber drivers quit the platform in droves, scared off by the risk of transporting sick passengers plus the lack of health care and sick pay, making ride supply short and prices sky-high. As rider demand began to recover but drivers remained hard to come by, Uber plowed $250 million into incentive pay and started partnering with that asshole named taxi to get the platform back to equilibrium.

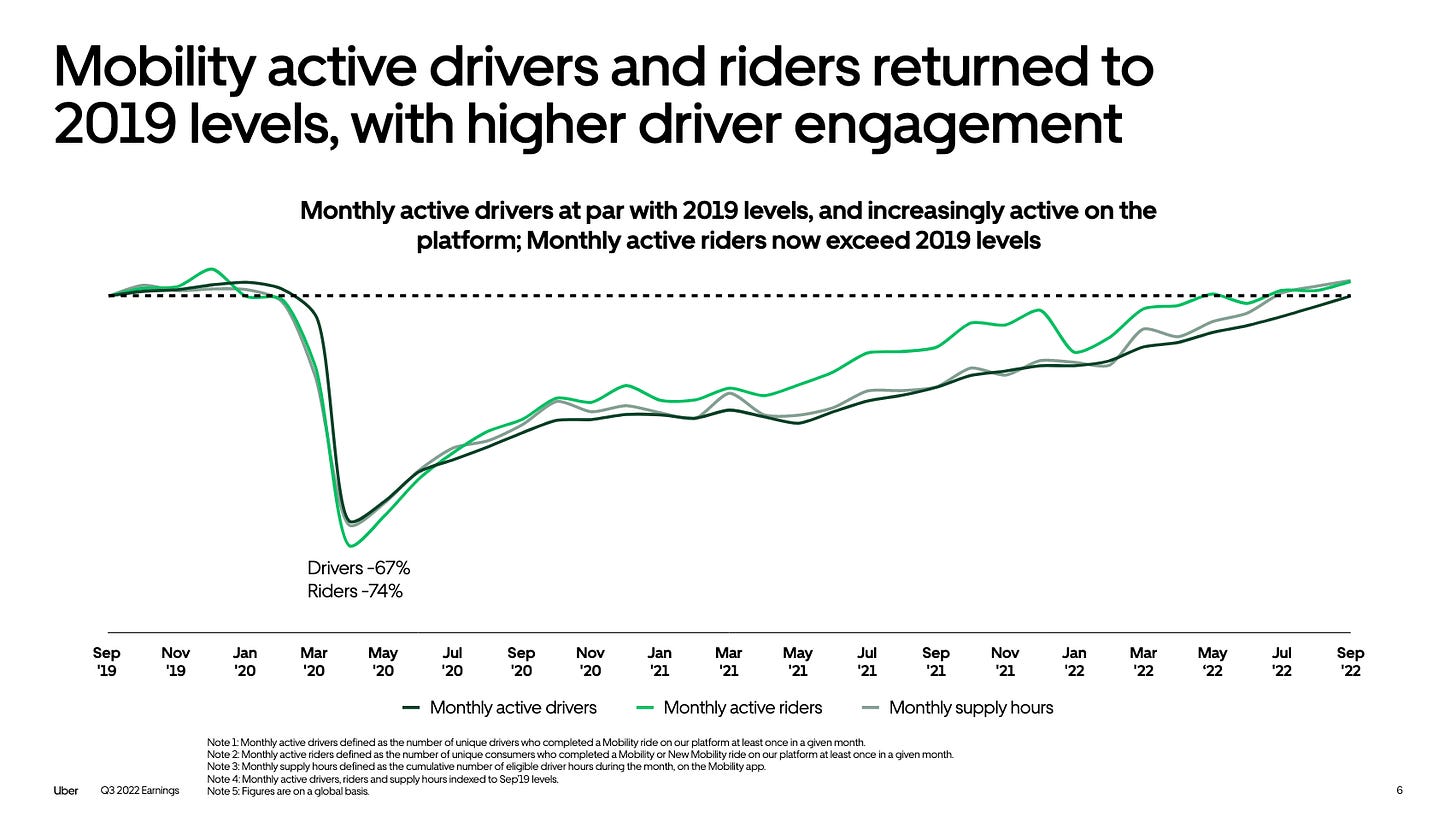

Now, though, in Uber’s own telling, driver supply is grand. Khosrowshahi told analysts that Uber’s U.S. driver supply is 80% recovered compared to 2019, while driver churn is down nearly 20%. “Driver engagement,” defined as the number of hours drivers work, is up 16% from the same time last year. “The trends that we see are very healthy and the competitive trends that we see in terms of driver engagement on our platform and drive preference for our platform remain very, very high,” Khosrowshahi said. In the latest quarter, this strong driver position came despite a “meaningful reduction in driver supply investments,” Uber reported, all of which boosted the company’s mobility segment adjusted ebitda to $898 million and a margin of 6.6% of gross bookings, a 1.1-percentage-point improvement from Q3 2021.

In other words, driver stuff is good, and Uber has even been able to trim its own spending in that area, but ride prices are still high. Because if customers are willing to pay where Uber used to subsidize, why bring them back down?

Here I’ll add a short anecdote: on trips to San Francisco between 2014 and 2018, I usually took a mix of public transport and ride-hail to get around, mostly in the form of the very cheap shared UberPools and Lyft Lines. But when I was in SF this September, ride-hail was so expensive that I walked and took transit everywhere. Even shared rides, back at last after a covid-era pause, were pricey. One afternoon Lyft quoted me $25.76 for regular ride or $19.66 for a shared trip (in 5-20 minutes) from the Marina to the Mission. Hardly the $3-6 shared fares you could get around the city in the heyday of ride-hail subsidies.

Because subsidies, after all, is what this is all about. Subsidies are the boon that made ride-hail a global phenomenon, and the curse that has kept any of these companies from becoming reliably profitable. Because it turns out that when you charge less for a service than it costs to provide it, it doesn’t matter how much scale or hype or hockey-stick growth you have—you still lose money. Can Uber ever be profitable? Sure, if it raises prices to the point where each ride and delivery makes a profit instead of a loss, something the company has historically been reluctant to do.

But then came covid, and the world changed. Drivers went away, carpool vanished, people stayed at home and ordered food and groceries to their doors. Covid, like inflation, was a challenge but also provided an opportunity to reevaluate. Slowly and steadily, prices ticked up, and customers kept paying. When Uber relaunched shared rides, it did so with a new focus on profitability, slashing the discounts and promotions that had made Pool incredibly cheap—and, according to Business Insider, led to annual losses of up to $1 billion for the company.

Meanwhile, Uber has also introduced upfront prices for drivers, a policy that has reportedly proved popular but also furthered decoupled what riders pay from what drivers earn, allowing Uber to increase its own take. In the latest quarter, Uber’s take rates on both rides and delivery hit all time highs, of 27.9% and 20.2%, respectively. Per Uber’s corporate filing, much of that high mobility take rate was due to “business model changes” in the UK, but even so, if you take a long view, the trend of Uber’s take rate has been up since the start of 2021.

The point is that Uber does have a path to profitability and it’s the one we’ve always known it would be: not a moonshot technology like driverless cars, but the tried-and-true strategy of raising prices, cutting subsidies, increasing its own cut. Here I’ll quote from my interview in July with the ever-prescient Marshall Steinbaum:

This is where we get into predatory pricing and whether that's what's going on. I think the other the other piece of the inflation story is basically recoupment from past predatory pricing. So with predatory pricing, it's suppose that all the competitors have the same cost of production, but one charges a lower price in order to drive everyone else out of business and claim the entire market. Then it becomes a monopoly. Then it can charge a higher price and make back all the losses it made when it was competing vociferously against the competition.

This is arguably what Uber is doing now, and why its fortunes are looking up. And inflation is part of what made it possible.

I certainly don't begrudge Dara presenting a very rosy picture of Uber's recent performance on his Q3 earnings call this week. That's his job, and he's VERY good at it.

But as you point out, the recent revenue gains have largely been driven by price increases, and we're not likely to see anything like the 72% Y-O-Y numbers that Dara crowed about, in the months ahead.

In round numbers, Uber's Q3 2022 # of US ridehail trips is down around ~30% compared to pre-pandemic Q3 2019, but average fares per trip is up by about 40%. In essence, Uber is trading off growth for profits (AKA decreased net income losses).

Bottom line, Uber is still enjoying high growth rates in revenue and rides YOY, relative to depressed year-ago pandemic levels. But relative to pre-pandemic demand, Uber is JUST getting back to its 2019 ridehail revenue level (after correcting for their accounting change), mostly because of price increases to offset declining trip demand (the two obviously being related).

What this portends is that Uber will NOT be able to sustain their current admittedly spectacular YOY revenue growth rates for two reasons:

1. Future growth rates will be pegged to current recovering demand levels, not depressed pandemic demand

2. There are limits to Uber's ability to continue to raise prices, particularly if we hit a recessionary downdraft.

One other point... Your latest Oversharing post noted that:

"This is the new Uber normal. It’s also a sign that upfront pricing—a dynamic pricing algorithm that charges individual customers their willingness to pay using a variety of information Uber has on them and their trip, also known as sophisticated price discrimination—is finally paying dividends."

I have a strong suspicion that Uber is increasingly exploiting first order price discrimination on both sides of its marketplace. But Uber has steadfastly denied that they set rider prices and driver pay, based on INDIVIDUAL passenger/driver willingness to pay or drive. I'd love to see proof from Uber that backs up their claim, or proof from a third party that backs up my suspicion!