Politics.

New York City is the first city to set a wage floor for ride-hail drivers and to cap the number of ride-hail vehicles on its streets, after the city council passed a package of bills on Aug. 8. Mayor Bill de Blasio is expected to sign the legislation into law today, and over the weekend drivers queued outside Uber’s office in Queens for hours to register their vehicles before the cap took effect.

The mayor has sought a cap on Uber since he failed to secure one in the summer of 2015, an embarrassing defeat made worse by Uber’s use of DE BLASIO MODE, an in-app stunt that showed long wait times and no Ubers in the outer boroughs. His stated reason: congestion. The mayor is concerned about the vehicles that crowd our streets and pollute our air. In 2015, he wanted to cap Uber to “study” congestion. After city council voted last week, he touted the cap as a fix for “the unchecked growth of app-based for-hire vehicle companies” and “the congestion grinding our streets to a halt.”

But let’s be honest, there’s a much better way to cap Uber in New York City: Fix the goddamn subway.

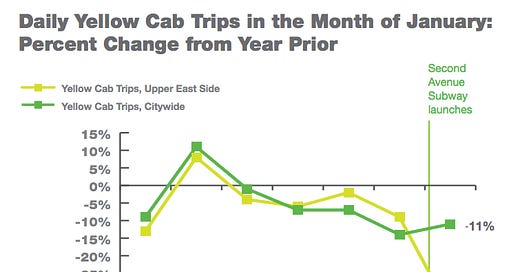

This is not just the opinion of a frustrated and weary straphanger. Research shows that when people have access to good public transit, they use cars less. The opening of the Second Avenue subway in the previously transit-starved Upper East Side offers a good case study. Since service began in January 2017, yellow cab trips have plunged three times faster than in the rest of the city, the local department of transportation reported in June. Similarly, ride-hail grew more slowly on the Upper East Side than in the rest of Manhattan, and at nearly half the pace of all five boroughs.

Where has De Blasio been through all this? Squabbling with the governor, squabbling with the governor about who will pay for the subway, talking up his Millionaire’s Tax, running red lights in his official motorcade, and, generally, not taking the subway. The mayor has also gone out of his way to oppose congestion pricing, a plan that not only would curb congestion by charging drivers to enter the busiest parts of Manhattan, but would also generate much-needed revenue to fund the subway rehabilitation.

Uber may have contributed to congestion in New York City but it is certainly not the root cause, nor will capping it fix congestion or do much to help stranded commuters. Local editorial boards were remarkably in agreement on this point, deeming the cap a “last-resort blunt instrument” and the case for it “weak.” Congestion pricing, fixing public transit—either of these would be far better options for reducing congestion than freezing the number of ride-hail vehicles. But this was never really about congestion. The mayor wanted a cap on Uber. And a cap is what he got.

Longhauling.

Elsewhere in Uber, the Wall Street Journal reports that drivers are taking riders the long way—“longhauling”—in an effort to get paid what they feel they are owed:

“If they were from out of town, I would take advantage of it by going the longer route,” said Ms. Blandy, who drove for Uber for about two years before moving to Harrisburg, Pa., earlier this year. “It’s the only way I could get what I was owed.”

In a modern twist on an age-old practice from the yellow cab industry, many drivers like Ms. Blandy are employing a practice known as longhauling—taking an unnecessarily longer route to a destination in order to drive up a fare. But unlike with taxis where passengers “get taken for a ride,” it’s ride-hailing companies like Uber Technologies Inc. that are responsible for covering the bigger bill.

Uber switched to upfront fares in 2016, in which the ride agrees to a price when the ride is booked while the driver gets paid based on miles and minutes. Since then, drivers have complained that the company sometimes takes too much. In some of the most extreme examples, drivers have shared screenshots that show Uber claiming 70% or more of the fare.

The idea behind longhauling is that it forces Uber—not the customer—to pay up (though passengers still pay with their time):

Passengers aren’t on the hook for the higher fare because they pay a fixed upfront price based on the app’s estimate of the ideal route. And while drivers are encouraged to go the most direct route, they can choose to ignore their digital navigators for a route that tacks on extra miles. The drivers’ pay is determined by the actual trip’s mileage and time, which can vary based on traffic conditions or diversions.

The trouble with upfront pricing is that it skewed the incentives. When drivers got a straight commission on every ride—typically 75%—they were better off doing trips as efficiently as possible, because more trips more reliably translated into more money than extending one trip beyond its normal length. Upfront pricing decoupled driver earnings from rider pay and put drivers back into a taxi-like fare system, where the duration of the trip became more important to their payout. No wonder they’re trying to circumnavigate the system now.

Scooters!

They are hitting road bumps:

Shortly after two startups dropped hundreds of scooters on the streets of Denver without permission in May, frustrated city officials responded swiftly with vehicles of their own. A platoon of workers in vans and pickups scooped up more than 300 of the scooters and impounded them.

Cities that feel they were too lenient with Uber and Lyft are determined not to make the same mistake this time around. Bird’s Travis VanderZanden prefers to frame it as the company taking a “collaborative” approach, he told the Wall Street Journal.

Of course, there is nothing like not getting your way to let the spirit of collaboration fly out the window:

Bird scooters has shut its service down in Santa Monica.

As CBSLA’s Jeff Nguyen reports, the company is staging a protest because the local start-up failed to top the list following an application review by a city committee for its electric bike and scooter program which is launching next month.

The city committee recommended letting Jump (Uber) and Lyft take the lead on shared e-scooters, a major snub to home-grown startup Bird. “Giving complete control of sustainable transportation alternatives to two ride-share corporations is like giving Exxon and BP Oil a monopoly on solar power,” Bird told riders in an email, collaboratively. It’s asking them to rally against the decision during a city council meeting this evening. I look forward to the collaborative attacks Bird will launch should the city council vote tonight to shut it out.

“What have we done.”

Uber whistleblower and soon-to-be New York Times technology opinion editor Susan Fowler is alarmed by the state of the gig economy. “The gig-economy ecosystem was supposed to represent the promised land, striking a harmonious egalitarian balance between supply and demand,” she writes in Vanity Fair. She continues: “Those of us on the front lines of the gig economy were the first to spot and expose its flaws.”

Here is my colleague Sarah Kessler, who started covering the gig economy in 2011 and has written an excellent book on it (check it out here):

Fowler’s piece concludes with her recalling a lunchtime chat with friends:

“Most people,” I said, interrupting the hubbub, “don’t even see the problem unless they’re on the inside.” Everyone nodded. The risk, we agreed, is that the gig economy will become the only economy, swallowing up entire groups of employees who hold full-time jobs, and that it will, eventually, displace us all. The bigger risk, however, is that the only people who understand the looming threat are the ones enabling it.

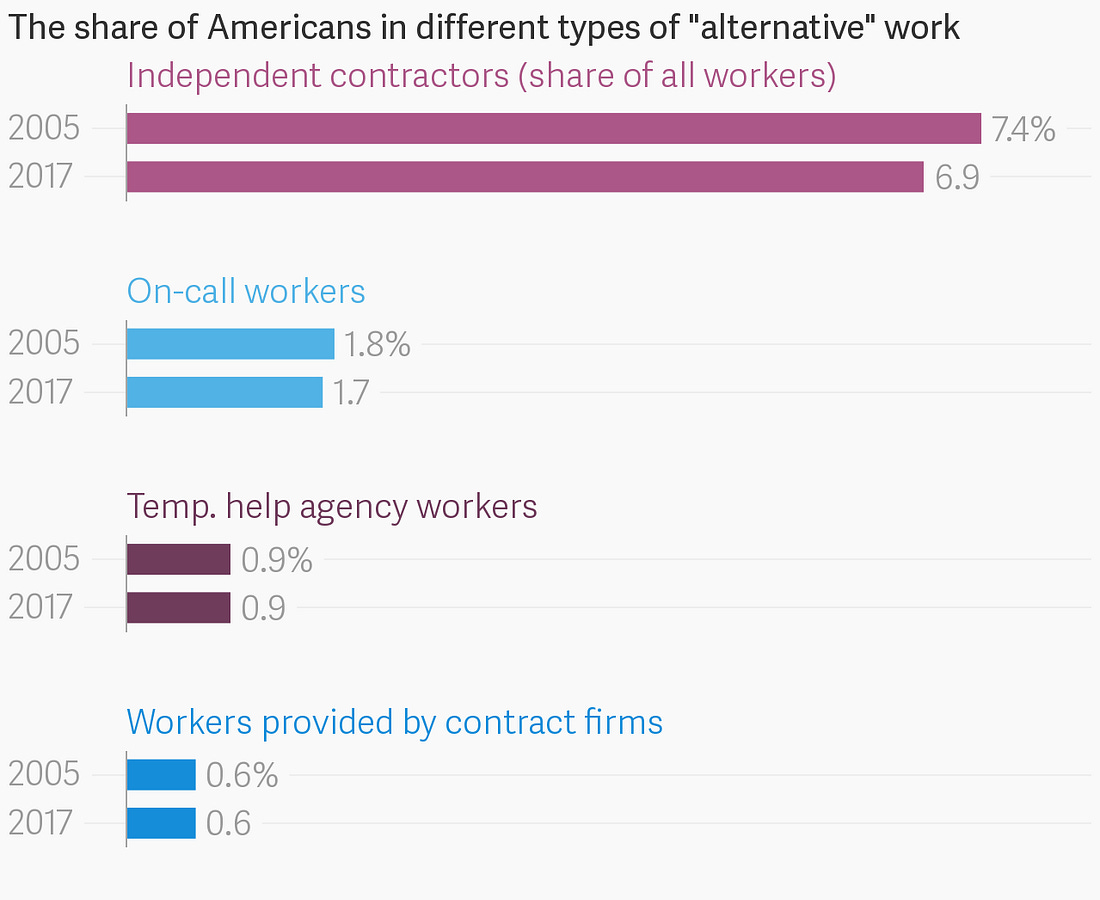

This fear of swallowing up is tempered somewhat by the June report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which found that the share of people working in “alternative” arrangements, an important government measure of gig work, had shrunk rather risen since it was last measured in 2005. The biggest decline came specifically in… independent contractors.

Other stuff.

Other stuff.

SoftBank portfolio companies help each other out. WeWork raises $1 billion in debt from SoftBank. Lyvly raises $4.6 million for shared living. Navya gets $34 million for driverless buses. Hostmaker seeks $32 million for rental property management. Ola names head of UK ops. Careem to test bus service in Egypt. Airbnb cancels Great Wall slumber party. Paul Manafort’s “Second Home” Was Always up on Airbnb. Chicago rejects 2,400 Airbnb host applicants. Airbnb for schooling. Points Obsessed Travelers Are Terrified of Losing Perks. This “Creepy” Time-Tracking Software Is Like Having Your Boss Watch You Every Second. How a Billion-Dollar Autonomous Vehicle Startup Lost Its Way. “Not everyone is comfortable with the idea of inexperienced start-ups lugging around tanks of flammable liquid.”