Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy.

If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here. This is issue ninety, published January 23, 2018.

SoftBank's ride-hailing empire.

Uber closed its deal with SoftBank last week, confirming in a statement on Jan. 18 that it was "proud to have SoftBank, Dragoneer, and the entire consortium in the Uber family." The deal gave the group of investors a 17.5% stake in Uber, with SoftBank retaining 15% to become the company's largest shareholder. SoftBank made a $1.25 billion primary investment into Uber at its previous valuation of $68 billion valuation, while secondary share purchases were made at a 30% discount, or a roughly $48 billion valuation.

The deal immediately kicked in governance changes that expanded Uber's board from 11 to 17 members, reduced the voting power of early shareholders, and limited the influence held by Uber co-founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick, who sold nearly a third of his 10% stake for about $1.4 billion. Venture-capital firm Benchmark is also dropping its lawsuit against Kalanick for "gross mismanagement and other misconduct." SoftBank has added two directors to Uber's board: Rajeev Misra, head of its $100 billion Vision Fund, and Marcelo Claure, president and CEO of Sprint Corporation.

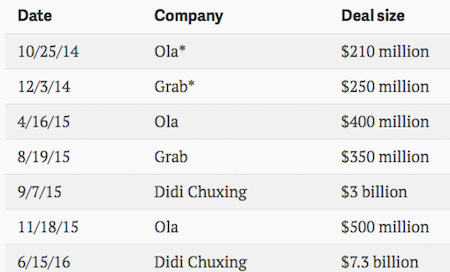

Uber is far from SoftBank's first ride-hailing investment. The Japanese tech giant previously put money into India's Ola, Singapore's Grab, China's Didi Chuxing, and Brazil's 99 (acquired earlier in January by Didi). Here's a list of all the ride-hailing funding rounds SoftBank has participated in, according to data from research firm PitchBook, with an asterisk on the deals SoftBank led:

SoftBank is now poised to use its considerable shareholder influence to broker deals between ride-hailing companies that might otherwise battle indefinitely and bleed each other dry. According to the Financial Times, Misra wants Uber to focus on growth in the US, Europe, Latin America, and Australia. He "insisted that existing unprofitable countries"—read, APAC—"was not solely about cutting its losses, which hit $1.5 billion in the third quarter of 2017, but that growth prospects were more promising in its core markets."

If SoftBank can convince Uber to pull out of India, Singapore, and other APAC markets, SoftBank wins. It secures landgrabs for Ola in India and Grab in Singapore and Southeast Asia. Didi has been largely in control of China since Uber sold its operations there in August 2016. Uber would be left with the US, Europe, and maybe Latin America and Africa. The resulting map would be one of regional dominance, with each local leader backed by SoftBank. It might not be the global domination Uber once dreamed of, but it would be a great outcome for its newly christened biggest investor.

Meanwhile, Dara Khosrowshahi has continued the global Uber apology tour, saying at a technology conference in Munich on Monday that Uber would focus on "responsible growth." "There is a rebel in every startup—I just think Uber took it too far," he said. "There was a bit of a pirate mentality."

Uber eats up Ando.

Ando started after celebrity chef David Chang abandoned Maple, the first delivery-only restaurant he endorsed, to test the concept on his own. Maple shut down in May 2017, crushed by high costs, but Ando remained, with Chang cautiously optimistic that a delivery-only restaurant could work. "At the end of the day, we're just a food company, we're not selling technology, we're just a restaurant," he told me at the time. "It's not ground breaking." In September, Ando opened a quick-service storefront near Manhattan's Union Square.

Three months later, the storefront is no more, and Ando has shuttered its remaining operations and sold to UberEats. "Starting Jan 22nd, 2018, we will no longer be serving customers in New York—online or via our Union Square location—as we will be immediately starting to integrate with UberEats," Ando said in a note on its website, alongside an image of a Philly cheesesteak.

Ando had ties to Uber. It used UberRush for delivery (before Uber shut that service down) and it was funded and incubated by Expa, a project of lesser known Uber co-founder Garrett Camp. In theory all of that could have made UberEats an easy exit for Ando, if the business had been going south.

What does UberEats gain from this single David Chang restaurant? One theory is that acquiring Ando helps differentiate UberEats by giving it exclusive "content," much as Netflix has invested in original programming. Other food delivery services have made similar moves: Deliveroo in the UK acquired Maple to help it develop satellite kitchens for restaurants, and DoorDash has also begun building and leasing kitchens to restaurants.

Silicon Valley's secret weapon.

Here is a profile in Wired of Margit Wennmachers, the "secret weapon" spin master behind Andreessen Horowitz and the archetypal nerdy startup founder:

We’re all familiar with Silicon Valley’s mythological image of the tech founder: brilliant, nerdy, eccentric, well-meaning. What you don’t know is that, more than just about anyone else in tech, Wennmachers is the person responsible for harnessing that prototype to build the legend of Silicon Valley. Before Andreessen Horowitz launched in the summer of 2009, most venture capital firms believed that no press was good press. They remained lean, behind-the-scenes outfits and won deals because of their back-room reputations. Wennmachers helped put the firm on the map by pushing its founders, Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, to embrace the press and by helping the companies in their portfolio articulate their ideas publicly.

Before she was an operating partner at Andreessen, Wennmachers co-founded Outcast, the now ubiquitous PR agency that reps a lot of tech startups. Her first breakout hit was Salesforce. Later Outcast repped Amazon, Facebook, and Etsy. Her co-founder Caryn Marooney went on to become head of global communications at Facebook. Wennmachers is known for her work in crisis comms:

Wennmachers has a strategy for dealing with any disaster, which she discusses at length in an Andreessen Horowitz podcast, “Crisis Communications.” First, get to the bottom of what happened. You rarely know it immediately, so take the time to do the digging. Second, communicate about it transparently. Don’t lie. Don’t take too long. If it takes a while to investigate the situation, tell everyone that! Tell everyone everything you can! Third, understand that a communications crisis is not a PR problem—it’s a business problem. Use the disaster to address the problem.

Digging! Transparency! Honesty! What kind of weird spin is this? What about scheming, lawsuits, board infighting, offering to pay hackers $100,000 to make it all go away? A theme of the Wired piece is how Silicon Valley has entered a new era, one in which the techies are no longer eccentric outcasts, but a new center of power. Wennmachers' challenge is getting modern tech leaders to take responsibility for their significant influence. The difference between her communications strategy and the methods more commonly deployed by startups should tell you what an uphill battle that is.

Tiny grocery warehouses.

"Imagine a world where it is cheaper to shop online than to go to the supermarket, and faster than if you were to go to the supermarket and go home," says Elram Goren, CEO of CommonSense Robotics.

It is a little hard to imagine, even in a world of Instacart and Amazon Prime Now, but let's try. CommonSense Robotics is designing small fulfillment centers near grocery stores, manned by robots. Robots climb the shelves, filling tote bags with products that they then deliver to human packers. "Because it avoids sending someone to hunt down products in the aisles of a store," Fast Company reports, "the system makes it possible to get a 20-item order from a service like Instacart ready in five minutes."

Generally speaking, there are two strategies in grocery delivery. The first is to have a big warehouse, like Amazon, and people who pick goods from it to pack and send to customers. The second is what Instacart does, i.e., to put professional shoppers into a traditional grocery store, and have them complete orders alongside normal customers.

Having a warehouse obviously requires a lot of space, and usually means the company owns the inventory and risks taking a loss on what it can't sell. The Instacart model takes advantage of existing stores and allows it to own no inventory, meaning no losses if the produce doesn't turn over in time. The CommonSense Robotics vision is sort of a hybrid of both of these—tiny grocery warehouses that complement neighborhood stores and fit in dense urban areas. The company is currently testing a prototype in an underground parking garage below its office building in downtown Tel Aviv.

"We're paying a fraction of the rent… we're using a lot less labor, and we're doing it a lot faster," Goren says. "It changes the economics of the situation, and that allows retailers to offer faster, cheaper delivery." Changing the economics of grocery delivery, of course, is something that a lot of companies would love to do, since the economics are not very good. CommonSense Robotics thinks it can cut costs by maximizing space and replacing humans with nimbler robots. The company reportedly plans to work with local groceries to help them compete against Amazon, which is basically the same model that Instacart embraced after Amazon acquired Whole Foods.

Elsewhere in grocery, Instacart acquired Unata, a Toronto-based startup that specializes in online coupons and circulars, in a deal valued at around $65 million. Unata is also developing voice-activated technology for shoppers, likely seen by Instacart as another way of competing against Amazon and its popular voice-activated assistant, Alexa. The acquisition "will create a one-stop shop for brick-and-mortar retailers to effectively compete in an increasingly online world," Instacart clarifies in its press release, just in case you weren't sure where it was going with that shtick.

Other stuff.

The Network Uber Drivers Built. Bozoma Saint John on a "personal mission" to help save Uber. Yahoo Finance wants to be the Uber of saving money. Belgium labor minister intensifies scrutiny of Deliveroo, UberEats. Independent contractors get a tax break. The Case for Letting Uber Drivers Organize. Uber Plans to Let Riders Request Better Drivers. Lyft says it's decreasing personal car use. Airbnb loses thousands of hosts in San Francisco. Boston to curtail short-term rental market. The Luxury Home-Rental Race Is Heating Up. Waymo heads to metro Atlanta. Lyft opens concierge feature to all businesses. Cabify raises $160 million. Cars designed for ride-hailing. Cargo raises $5.5 million. Google invests in Go-Jek. Uber CEO predicts flying cars in 10 years. NY judge rejects proposed class-action settlement with Uber drivers. Uber's two-factor authentication was flawed. Tim Cook doesn't want his nephew on a social network. Anthony Levandowski sued by his children's babysitter. Brian McClendon running for Kansas secretary of state. Tech Leaders Are Starting to Say They Welcome Regulation. There's never been a better time to be a statistician. The case for shared-use mobility zones. The problem of fleet relocation. "I don't think they need to get Taylor Swift on the platform to be successful."

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and honest crisis communications to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.