Scooters!

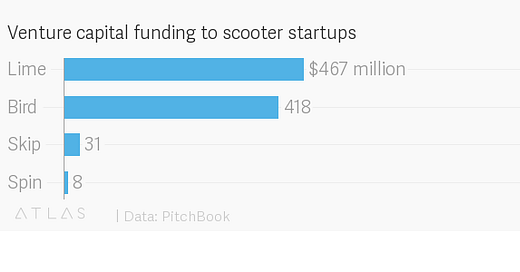

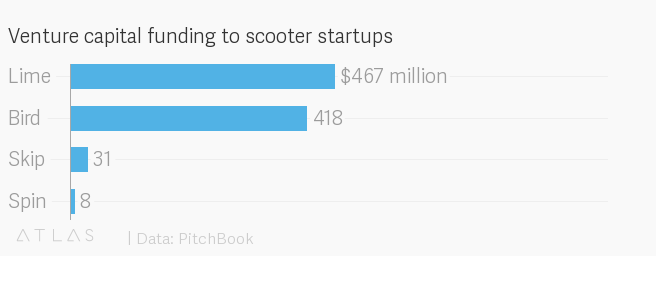

The newest scooter unicorn is Lime, which yesterday (July 9) announced $335 million in new funding at a $1.1 billion valuation. The round was led by GV, Alphabet’s investment arm, and included a “sizable” contribution from Alphabet frenemy Uber Technologies Inc. That brings total financing to scooter companies to about $900 million. Uber is joining Lime as a “strategic partner in the electric scooter space,” and will co-brand with Lime to offer scooters through the Uber app.

What are the unit economics of scooters? Here is some quick math on Bird:

In Santa Monica, Bird’s first city, the average Bird scooter does 5-6 trips per day, Bird disclosed at a June city council meeting

The average length of a Bird trip is 1.6 miles (same city council meeting)

Bird charges $1 per trip plus $0.15 per minute

Assuming an average speed of 7.5 miles per hour, the average trip lasts 12.8 minutes

In which case the average trip costs $2.92

At 5.5 trips per day, the average scooter earns about $16 a day

Not bad, right? The Xiaomi scooter that Bird uses sells for about $500 on Amazon but $320 (1,999 yuan) in China. I don’t know what Bird pays for a scooter, but: If we assume Bird is paying the China price or less because of a bulk deal, it would recoup the initial capital cost in 20 days. If we assume the Amazon price (unlikely as Bird has a contract with Xiaomi), then the scooter would recoup its overhead in just over a month.

The real question is what a scooter costs to service and maintain. We know that Bird hires contractors to charge its scooters overnight and redeploy them in the morning, usually for $5 per scooter. A typical charge takes 3-5 hours, and by farming this out to eager contractors, Bird conveniently avoids the electric bill. That brings our scooter revenue per day down to $11. Here are some other costs we don’t know:

The lifespan of a scooter/how fast it depreciates

Other maintenance costs associated with a scooter

Operational costs like “rebalancing,” aka the amount Bird pays workers to redistribute its scooters each day, averaged out to a single scooter

You can see how all that would start to add up.

A source familiar with Lime tells me that revenue per day, per scooter, in San Francisco is much higher than the Santa Monica numbers would suggest, in the mid to high twenty-dollars. This person also said that daily depreciation and operational costs are significantly higher, which would make sense with greater utilization. Even so, Lime believes the payback period on a scooter, including initial purchase price, daily depreciation, and operational costs, is less than two months. After that, each scooter basically prints money, with margins that are much better than those of an e-bike or traditional bike. Lime also believes it can improve on these unit economics.

That leaves the final, less predictable cost: regulations. Cities are still working out how to deal with scooters, and the economics of the business will ultimately depend on the regulatory schemes that governments impose. In Portland, Oregon, for example, the city has proposed a $0.25 surcharge per ride, in addition to permit fees of $5,250 ($250 to apply, $5,000 for the permit, if selected) to deploy up to 200 scooters for four months. At 200 scooters, that works out to an additional $26.25 in permitting fees per scooter, plus $1.25-$1.50 in daily ride surcharges, if you assume 5-6 trips per day—and that’s just for the first four months. Convincing cities to adopt a gentler fee structure will be crucial for scooter companies to make the model work.

Trojan scooters.

Elsewhere in scooters, who would have thought that Xiaomi, the so-called Apple of China, would have a breakout hit in the US with electric scooters?

Xiaomi, one of the world’s largest smartphones manufacturers, has emerged as a leading supplier of scooters for Silicon Valley transit startups. Rebranded Xiaomi scooters have been deployed across US cities by scooter unicorn Bird, which in May reportedly locked in Xiaomi for tens of millions of dollars as one of its vendors. Xiaomi scooters have also been used by Spin, a Bird competitor. It’s as though Apple went to China and became a sensation for the AirPod.

The other major scooter maker is Segway/Ninebot (it supplies for Lime), which has a close relationship with Xiaomi and counts it as a backer. Xiaomi couldn't be reached for comment to clarify the relationship.

Xiaomi had a lackluster debut on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on July 9, closing at HK$16.78, below its list price of HK$17. The company’s IPO inauspiciously coincided with the start of a massive trade war between China and the US, with tariffs on $34 billion in goods, including scooters.

Xiaomi doesn’t currently sell smartphones in the US, though it said in March that it could enter the market by late 2018 or early 2019. That would pit it against established US smartphone brands like Apple and Samsung, and other more affordable Chinese imports, like OnePlus. It could also subject Xiaomi to the sort of espionage concerns that kept Chinese telecom company Huawei out of the US for years, and reportedly torpedoed a deal between Huawei and AT&T earlier this year. The US intelligence community has specifically warned against using Huawei phones.

On the other hand, scooters aren’t smartphones. We don’t use them to make phone calls and send emails and texts (at least, not yet!). They gather information, sure. Bird, per its privacy agreement, collects things like payment information, user account details, and communications with customer service through its app, as well as battery status and location from the actual scooter. That’s not nothing, but it seems fair to say that no one is worried about espionage via scooter.

Parking lots to pumpkin patches.

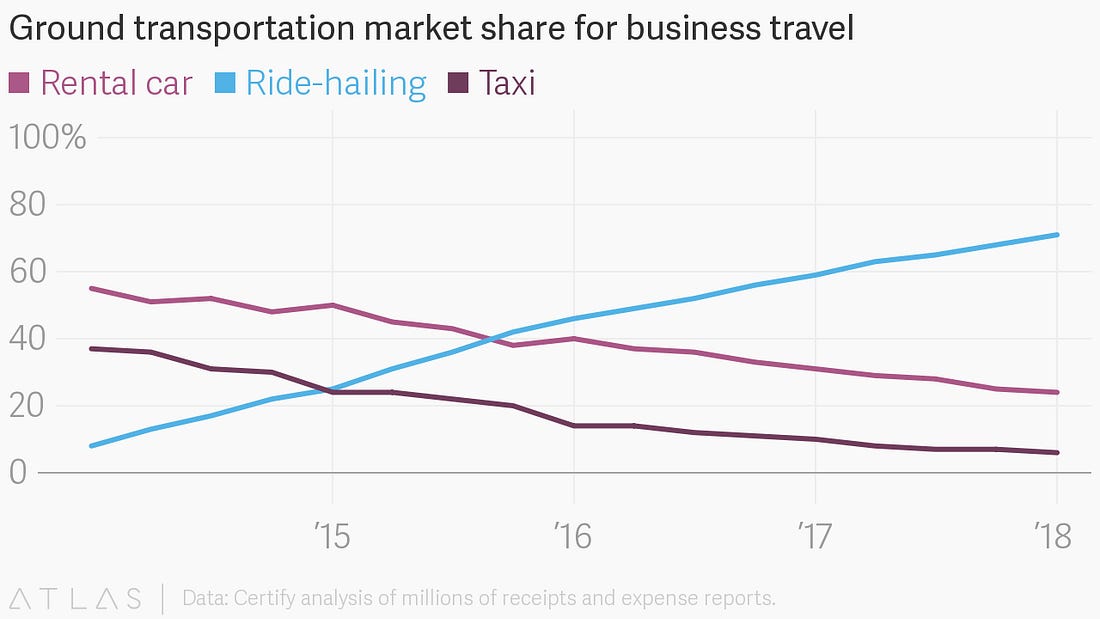

The obvious industry that ride-hailing has hurt is taxis, but it’s not the only one. We talked a couple months ago about how Uber and Lyft, combined with new car-sharing startups like Turo and Getaround, have made life hard for rental car companies. Rental car companies have bled market share in business travel, for example, as those customers have overwhelmingly shifted to ride-hailing.

Proper Parking, based in Woodland Hills, has seen a 70% drop in nightclub valet traffic since it started six years ago, said Brandon Helfer, the company’s president. In addition, it has seen a 30% drop in restaurant traffic and a 25% drop at weddings.

“At some nightclubs, we used to park 60 or 70 cars per night,” Helfer said. “It got to the point where we were parking 10 to 20.”

The steep drop in demand has forced Proper Parking to put its parking lots to other uses:

In October, Proper Parking turns nine of its asphalt lots into hay-filled pumpkin patches called Mr. Jack O’ Lanterns Pumpkins. Come Christmastime, it runs tree-selling operations there dubbed Mr. Jingles Christmas Trees.

This is obviously bad news for Proper Parking but it is also… kind of exciting? It is sort of real-world proof of what Uber and Lyft have been saying for years, that ride-hailing cuts down on personal car use. Reducing personal car use is obviously good for emissions, especially if you are getting more people into shared rides, but it also affects how we think about public space. If fewer people are driving their own cars, then fewer people need to park those cars, and huge swaths of land that we’ve devoted to asphalt parking lots can be put to other, perhaps better, uses. I would certainly take a hay-filled pumpkin patch over a car-filled slab of concrete any day.

The kitchen is closed.

Here is a fun story from Nellie Bowles at the New York Times on restaurants that double as co-working spaces:

Everything is now a co-working space, one of those shared offices that are popular among freelancers, small companies and other workers who want a change of scenery. Coffee shops are co-working spaces. Gyms are co-working spaces. Social clubs are co-working spaces. And now restaurants — but only before dinnertime.

The startup in question, Spacious, has converted 25 fancy restaurants in New York and San Francisco into weekday offices for members, who pay $99 (per month for a year) or $129 (month by month) to enter any location. Spacious raised $9 million in May and plans to expand to 100 spaces this year. Here is the really interesting bit:

Originally, the founders of Spacious thought they would have to sell restaurateurs on the idea. Instead, restaurants, struggling to pay rent and wages and frustrated with disappointing lunch traffic, are coming to them, eager to strike deals for a slice of the membership dues. Only 5 percent have made the cut to become Spacious spaces, said the company, which is unprofitable.

This makes sense. We have talked before about how restaurants have notoriously terrible margins, usually in context of why that makes it hard for delivery companies to eke out much money from restaurants in the first place. It’s also well known that one of the main costs for a restaurant, particularly in a city like New York or San Francisco, is rent. That was the original pitch for startups like Maple and Ando—a delivery-only restaurant that avoided that massive overhead by only paying for the space it needed to prepare the food.

But what if instead of eliminating the dining space, you could just get more use out of it? That seems to be the idea behind Spacious, which realized that many restaurants are under-utilized outside of dinner, and could be putting their pricey, well-designed and decorated spaces toward a more lucrative purpose:

Justin Sievers, 34, the managing partner of Bar Primi in Lower Manhattan, saw Spacious operating at a restaurant nearby. With lunch traffic low, he said, he decided to be “inventive” and reached out to the start-up to make Bar Primi a co-working space during the day.

“It’s not what we want our space to be, and there is a little bit of this negative connotation of ‘O.K., we’re a restaurant, but we have to now sell out a little bit of our dining room for all these laptops?’” Mr. Sievers said. Now he is less worried about how it looks.

“Laptops used to send the message that we’re failing as a restaurant,” he said. “But that’s changing.”

Other stuff.

Airbnb hires Tao Peng as head of China business. Grab aims to be a one-stop “super app.” Singapore antitrust regulator threatens Uber-Grab deal. Uber in talks to merge with Dubai-based Careem. Uber is back in Finland. Baidu readying a driverless car service in China. Is Ride-Share the New LinkedIn? Uber and Lyft considered buying Skedaddle. WeWork rival Convene raises $152 million. Uber seeks IPO Readiness Manager. The future of urban transportation is the bus. Driverless cars near AI roadblock. In This Economy, Quitters Are Winning. “WeWork has a business model underpinned by unglamorous property market arbitrage.” An Immodest Proposal: It’s Time for Scooter Superhighways.