**Important: Oversharing is moving to a new home on Tuesday, June 26.** It's been a good run on TinyLetter, but, as you may or may not know, TinyLetter's time is limited. The newsletter product is slated to be integrated into MailChimp some time in the vague and distant future. While MailChimp Ben Chestnut initially said the changes wouldn't happen this year, the company now seems to be hastening TinyLetter's demise by declining to make it GDPR compliant.

As much as I will miss TinyLetter and its weird formatting quirks (I see you, ), I am very excited to say Oversharing has found a wonderful new home on Substack, a recent graduate of Y Combinator. Starting June 26, Oversharing will arrive from oversharing@substack.com, so you should go ahead and white list that email in your inbox. (This is also a good time to make sure Oversharing hasn't been accidentally filtering into any of your other email folders.)

It is a big transition but I promise we will get through it together! In the meantime, send questions, comments, and concerns to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.

Scooters!

Unfortunately, the Electric Scooters Are Fantastic:

On that first ride, a few things became apparent. First, I was more likely to respect traffic laws on a scooter than on a bike, because I wasn’t as worried about conserving my momentum on a scooter. Second, riding a scooter is reminiscent of riding a Segway—even if you, like me, have never ridden a Segway in your life. It turns out that even Segway virgins like myself immediately intuit the unnaturalness and awkwardness of standing-still-while-moving-quickly-forward. It feels kinetically uncool; it’s the posture of conspicuous tourists and safety-vested traffic cops. Third, the personal-injury lawsuits over these things are going to be spectacularly lit.

And yet I couldn’t quit the scooters. The next day, I took a scooter to work again, even though I wasn’t running late. The day after that, I took a scooter four miles across the city to a baseball game. The following week, after an early-morning appointment, I spent 20 minutes searching the neighborhood for a scooter so that I wouldn’t have to take a Lyft. I now check the app every morning to see if there are scooters nearby.

The war is over and I have lost. I love Big Scooter.

(The exception to this, the author adds later, is that he would not ride a scooter to a date.)

Unfortunately, this newfound scooter-love was also ill-timed: The scooters are gone.

As if by magic, the scooters are gone.

The hundreds of for-rent stand-up electric scooters that appeared on San Francisco streets almost overnight in late March, drawing both fans and haters, have disappeared just as quickly — but could return within weeks.

The city mandated that all the rental e-scooters must cease operations by Monday while the companies behind them apply for permits.

Bird, Lime, and Spin removed their scooters yesterday (June 4) and are waiting to receive permits to operate legally. Applications for those permits are due Wednesday (June 6) and San Francisco's transit authority is supposed to decide who gets one by the end of the month. The pilot program allows permits for five companies, with each capped at 1,250 scooters for the first six months.

"We are pleased that it appears the companies are following the law," says transit spokesman Paul Rose, surely a rare sentence for anyone to utter in Silicon Valley. And here is San Francisco Transit Riders board member Daniel Sisson summing up the situation: "It's so typical of both San Francisco and Silicon Valley: The tech companies jumping out there and doing what they wanted, and then the city overreacting."

Elsewhere, Bird could become the first scooter unicorn, thanks to $150 million it's raising in a round led by Sequoia at a $1 billion valuation. The next best-funded scooter startup is Lime, which has raised $132 million to date, though it's reportedly looking to raise as much as $500 million through debt and equity, and may be close on $250 million led by GV. Spin is eyeing funding worth "tens of millions" according to PitchBook, and otherwise hasn't raised money since May 2017. And let's not forget about Goat, the newest member of the single-syllable scooter club, which is "currently bootstrapped," according to TechCrunch. Add that all up and you have more than $400 million behind electric scooters companies to date, with much more than that in the pipeline. I guess the funding bubble has yet to burst.

Labor force characteristics.

Back in the very first issue of this newsletter, we talked about how the so-called gig economy was a segment of the economy that we knew startlingly little about. In truly epic bad timing, the Bureau of Labor Statistics eliminated its contingent work survey, which studied flexible and on-call work, in 2005 when it ran out of funding. Just a couple years later, of course, the gig economy came into being and the number of people working in on-demand jobs swelled, not that the labor department was keeping track.

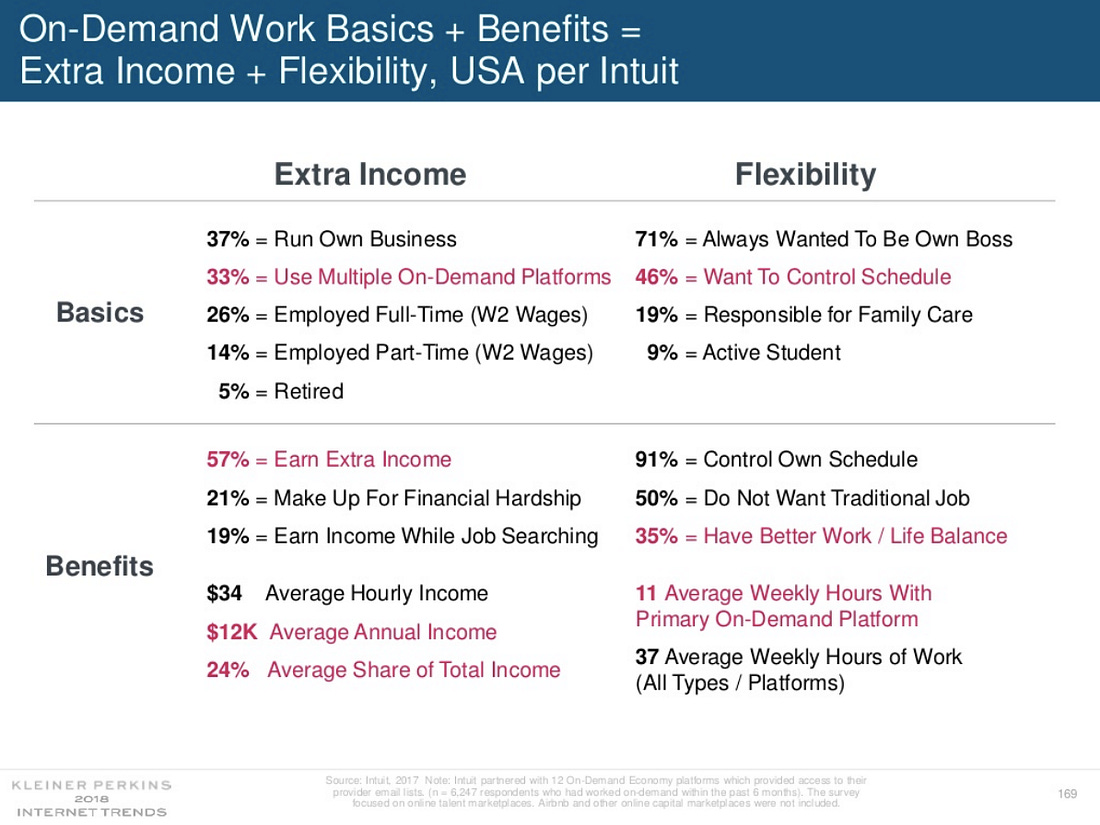

Research since then has been scattershot. Much of what we claim to know about the gig economy comes from research funded by gig companies themselves, meaning it is almost definitionally unreliable. The research featured in this year's Mary Meeker Internet Trends report, for example, was provided by Intuit, Checkr, Uber, Etsy, DoorDash, Upwork, and Airbnb, all of whom would like to see the gig economy grow. The overview Meeker compiled of gig work from this data was noticeably light on disadvantages and heavy on gig economy benefits, like flexibility and extra income.

That's finally about to change:

For the first time since the rise of the term “gig economy,” the US federal government will release data showing how many workers rely on non-traditional work arrangements like temp work, freelancing, and on-call work.

The June 7 disclosure has been much anticipated. According to research conducted in the past decade, anywhere from between 0.1% of U.S. employment to 34% of the workforce can be categorized as part of the gig economy—a variance that can largely be explained by inconsistent definitions of the buzzphrase.

The BLS study will look at the number of contingent workers (people who didn't expect their jobs to be permanent) and workers in "alternate" arrangements, such as temp and contract work, in addition to independent contractors. That's a much wider sample than what we tend to think of as the gig economy, covering many industries where outsourcing and temporary staffing plays a significant part.

The BLS did do some work specifically around the digital gig economy. Part of that included designing a new questionnaire to measure digital on-demand workers, and in 2016 the BLS advertised on Craigslist for gig workers to come to its offices in DC to try out some of the new surveys (it paid $40). The BLS ultimately added four questions to its Contingent Worker Supplement, "designed to identify individuals who found shorts tasks or jobs through a mobile app or website and were paid through the same app or website." Unfortunately, we won't get the good stuff this week, as "BLS continues to evaluate these data and plans to publish the findings from this research at a later date."

In the middle.

Amazon is off the hook for selling hoverboards that exploded because it wasn't a "distributor," "retailer," or other "entity engaged in the business of selling a product," a court ruled last week. "Amazon's role in the transaction was to provide a mechanism to facilitate the interchange between the entity seeking to sell the product and the individual who sought to buy it."

If this logic sounds familiar, it's because similar ideas are espoused by many a sharing economy company, which are, variously, not taxi services, not cleaning services, and not lodging providers, but simply platforms that connect a person who wants to buy a good or service with another person willing to provide it. Being a digital "platform" has helped Uber keep its workers defined as independent contractors, and Airbnb to evade safety and building requirements followed by hotels. It also extends beyond the sharing economy: think Facebook, the media and content company that isn't a media company.

Of course, the downside of this middleman life is that sometimes things get out of control. Handy, for example, settled with the attorney general in Washington DC last summer over customers who alleged the company's hired cleaners stole things from their homes. The complaint, filed in September 2016, had alleged Handy "does not adequately check the background of its cleaning professionals, and individuals with prior criminal convictions or that are likely to steal from consumers have been accepted by Handy."

Uber spent years fighting stringent background checks in US states that wanted a fingerprinting requirement, arguing that it would be too burdensome for the service. (It usually won those fights, except for in Austin, Texas.) Now, though, the company is suddenly under more scrutiny for its safety processes, including those background checks:

Among the shady drivers who cleared Uber's screening process: A man convicted of attempted murder who is now accused of raping a passenger in Kansas City; a murderer on parole in Brazos County, Texas; a previously deported undocumented immigrant who is now facing trial for sexually assaulting three passengers and attacking another in San Luis Obispo, California. They no longer drive for Uber.

Rideshare companies Uber and Lyft have approved thousands of people who should have been disqualified because of criminal records, according to state agencies and lawsuits examined by CNN.

In statements to CNN, Uber and Lyft said their background checks are robust and fair. Uber acknowledged past mistakes in its screening process, but said, "More than 200,000 people failed our background check process in 2017 alone. While no background check is perfect, this is a process we take seriously and are committed to constantly improving."

Being a middleman lets you evade a lot of legal liability (it's not my product; I'm not the employer; I don't own the building; etc.), but it also comes with a certain amount of reputational liability. That doesn't seem to matter when most consumers love your company, but as soon as public sentiment turns, as it has for Uber and Facebook, and could very well for Amazon, it can be a real problem.

Frenemies.

Remember that time Waymo sued Uber for allegedly stealing its intellectual property, and they went to trial and lots of heated emails came out about Uber poaching Google talent and Travis Kalanick wanting a literal pound of flesh? I mean lol who remembers that:

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi says that his company is in “discussions” to have Waymo self-driving cars added to its network.

There is of course the benefit of Waymo's cars not having killed any pedestrians yet, something Uber presumably finds attractive. That said, it is a little unclear why Khosrowshahi thinks Waymo would be interested in helping it out by licensing cars to it or anything else. His answer for now is apparently "economics," which, ok, Uber has a big platform with a lot of rides, but in terms of actual self-driving technology it would seem like Waymo has much more leverage. Ride-sharing platforms are not exactly in short supply: there is Uber and Lyft in the US and other smaller companies in other cities, not to mention internationally. Waymo could also probably make its own ride-sharing platform and integrate it through something like Google Maps or Waze that a lot of people already use. Why would Waymo choose to work with Uber unless Uber cut it a really great deal?

Meanwhile over in Japan, driverless cars could be on public roads in Tokyo in time for the 2020 Olympics, the government said this week. Per Reuters, economists are interested in autonomous technologies as a solution/coping mechanism for Japan's aging population, which makes a lot of sense. It would be ideal if driverless cars rolled out first to groups of people that you probably don't want driving around themselves, so, the very old, and the very sleep deprived (think medical residents who have just left a 24-hour shift). Japan has the oldest median age of any large country, and its proportion of over-64-year-olds is expected to reach 38% of the population over the next five decades. Driverless cars can't get there fast enough.

Other stuff.

Venture capitalists are losing leverage to star entrepreneurs. Ford's Chariot scrutinized for lobbying activity in San Francisco. Lyft plans to acquire bike-share operator Motivate. Chinese Women Are Hiding Their Faces After a Ride-Sharing Murder. SoftBank plans $2.25 billion investment in GM's self-driving unit. Disruptors Don't Stand a Chance Against Car Companies. Waymo orders 62,000 Pacifica minivans to build self-driving fleet. Waymo could claim electric vehicle tax credits. Waymo pranks. Careem weighs $500 million in funding. Airbnb gets green light in New South Wales. Hello Alfred raises $40 million. Company wants to put "brains" in electric scooters. Amazon challenged in UK for saying workers are self employed. Howard Schultaz steps down from Starbucks. New York dedicates parking spots to car-sharing. "Contract formation processes are now failing that historically would have succeeded." EU investigates Chinese bike companies. London's Evening Standard sold positive coverage to Google and Uber. Google Maps, Please Chill. Your Retirement May Be Saved by a Side Hustle.