An important note.

This is the last time Oversharing will come from TinyLetter. It's been a good run, but TinyLetter is being phased out. Starting Tuesday, June 26, Oversharing will be published on Substack and arrive in your inbox from oversharing@substack.com.

Do I need to do anything? Nope. I will transfer your email to Substack.

What if I don't get Oversharing next week? Check in your spam folder, under the "promotions" tab in gmail, and search for the new sending address, oversharing@substack.com. If all else fails, email me at oversharingstuff@gmail.com (that address is not changing).

What if I already went ahead and signed up on Substack? Congrats! You are one of my beta-testers. I'll try to make sure you don't get it twice next week.

Are you still accepting tips and gifs? Always.

Good for business.

If you are a cynic like I am, then you believe most companies don't do good things unless there's something in it for them. That's the lens through which I read this Fast Company story that WeWork has hired 150 refugees and plans to hire 1,500 total over the next five years, a commitment WeWork CEO Adam Neumann denies is a political statement.

Many refugee hires start out cleaning and managing WeWork's office spaces, but the company is reportedly testing programs to help them move up the ladder. "We look at these [roles] as starting places," says WeWork exec Mo Al-Shawaf. "We also want to make sure that we're investing in your growth and that you have those pathways to able to grow within WeWork."

If not a political statement, why do this? Maybe because it is good for business:

WeWork members have been overwhelmingly supportive of the program, Al-Shawaf says. That’s in contrast to the experience of some other companies that have made large commitments to hire refugees; when Starbucks announced a plan in 2017 to hire 10,000 refugees globally by 2022, it faced a backlash from some customers (and praise from others). Chobani, similarly, was targeted with threats and a boycott from white nationalists for its own hiring of refugees.

WeWork built a multibillion-dollar business selling millennials on hip communal offices with beer-on-tap; now, in our fraught political era, it also has to cater to those millennials' values. Uber learned this the hard way in early 2017 when its users revolted over the misperception that the company and Travis Kalanick supported Donald Trump. Around that same time, dozens of other tech companies took public stances against Trump's immigration policies, emboldened by immigrant coworkers but also customers who were overwhelmingly liberal and overwhelmingly deplored the Trump administration's actions.

Technology companies are now once again emerging as leaders in corporate America on condemning the Trump administration's cruel policy of separating children from parents at the US-Mexico border. Microsoft, Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian, Twilio CEO Jeff Lawson, and all three Airbnb co-founders have denounced the policies; Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg both donated to a fundraiser to help reunite families that raised nearly $5 million.

It is impossible to know whether technology companies are doing these things because they are morally good, or because they are good for business; whether that matters to you depends on your school of ethics. You might believe the outcome supersedes intent, or you might feel the end result is sullied if the original intent was selfishly motivated. Maybe that's why WeWork doesn't want to call it politics; sometimes the moral complexities are easier to sidestep if you just think of it as business.

Carrot and sticks.

Seattle has "taken to dockless bike sharing like nowhere else in the country," says Wired, with more than 350,000 riders who have covered 1 million miles in just five months. Like other cities that have been flooded with dockless bikes, Seattle has run into a few challenges: bikes piled up at popular destinations, stranded at other unpopular ones, left in the road, left on the train tracks, and even tossed into lakes. ("Three out of four times when we dive downtown on the waterfront now, there's a bike in the water," says scuba instructor Mike Hemion.)

The most interesting part of the story, though, is buried at the end, about what happened when dockless bikes set up on the University of Washington campus. According to Wired, the university and bike share companies started to clash last fall when workers for Ofo, a Chinese bike share startup, repeatedly used campus bathrooms. In November 2017, the University of Washington banned Ofo from leaving any bikes on its grounds. Then it reconsidered: Instead of flatly banning dockless bike share, the university decided it would charge companies for the right to operate on campus property:

It recently put out a request for proposals for bike share schemes that came with strict contractual terms. They include offering a 50 percent discount on campus and allowing the university to impound any bike "at any time for any reason or for no reason."

Those weren't the only conditions:

A key requirement of the university, which all three companies agreed to, is to set up geo-fences to force bikes to be parked only in permitted areas. If a bike's GPS senses it is being locked outside an authorized area, the app will warn the user.

Did the bike share companies scream and cry luddite, as transit startups confronted with rules by local governments are so fond of doing? No! They agreed to all of it, and more:

Spin and LimeBike said they might impose a fine on riders who disobey, and all three said they would restrict or even ban habitual bad parkers. Good behavior, on the other hand, could be rewarded with free rides. "We are currently testing a carrots/sticks approach for smart parking, including bonuses for parking in a preferred location," wrote LimeBike in its response to the university. All the companies agreed to a one-hour response time for badly parked bikes, at the university's command.

They also agreed to pay the university for operating on campus, albeit at different rates. LimeBike suggested an annual $5 per bike fee to cover the university's costs for managing the parking infrastructure and other aspects of the scheme. Spin proposed handing over 10 percent of net profits; Ofo was more generous, offering 10 percent of its revenue from rentals on campus. The university says it is still negotiating the contracts but hopes to sign them soon.

I am honestly not quite sure of what to make of this. Perhaps startups have a higher opinion of University of Washington than the typical local government, and so think the university is more likely to enforce a full-on ban. Perhaps the business potential at University of Washington, a campus of 634 acres with 31,000 undergraduates, is too great for bike share startups to ignore. Maybe the university was onto something with its request for proposals, an Inception-like trick that allowed the startups to feel as though they were writing the rules, when in reality they were mostly complying with the university's terms and conditions. University of Washington started with a stick and ended up with a stick disguised as a carrot, and it worked. It is a great mystery, but one worth trying to replicate.

Also: Uber Wants to Join Seattle's Bike-Share Battle.

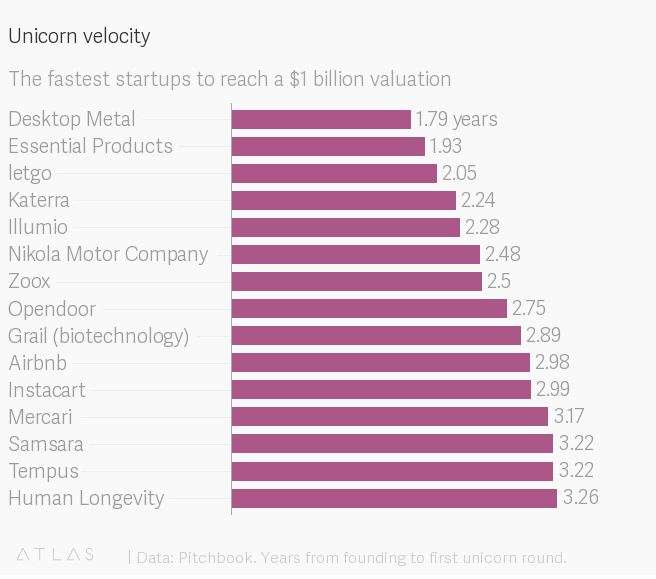

Unicorn velocity.

Elsewhere in micro-transit, Bird is the fastest startup ever to become a unicorn:

“Unicorn” startups valued at or above $1 billion are no longer extraordinary in Silicon Valley, with well over 200 companies on a list maintained by venture-capital research firm CB Insights.

But Bird is still remarkable for how quickly it achieved unicorn status. Founded in September 2017, Bird hit the $1 billion marker in well under a year, the fastest ever. The previous record from founding to unicorn was 1.79 years, set by 3D-printing company Desktop Metal, according to a ranking compiled by VC research firm Pitchbook.

Bird's last announced funding was an $100 million series B in March, but the company has money in the bank for both parts of its two-part series C, the first at a $1 billion valuation and second at a $2 billion valuation. Here's the pre-Bird ranking of how quickly startups became unicorns, according to Pitchbook:

Please be advised that Unicorn Velocity will be the name of my new band, performing music in the style known as desktop metal.

Safety first.

The Uber-Waymo trial didn't clear up whether Uber stole any of Waymo's trade secrets, but it did crystallize just how Waymo would like to be perceived in the driverless car space relative to its competitors and particularly to Uber. Waymo hammered home its focus on safety. "It's the thing that we're most focused on," Waymo CEO John Krafcik said. "We're driven by safety at Waymo."

Waymo's safety-first strategy was set up as a foil to Uber's win-at-all-costs approach, for which former autonomous vehicles head (and alleged IP theft) Anthony Levandowski was the poster child. I mention this because months after the case was settled and trial concluded, Uber continues to play into Waymo's hand on this narrative:

When a self-driving car prototype operated by Uber fatally struck a pedestrian in Tempe, Ariz., in March, Uber quickly identified the likely cause in software that caused the vehicle to ignore certain objects that its sensors detected. But a further realization dawned on some executives and members of the team: The rush to develop a commercial self-driving vehicle had led Uber to de-emphasize computer simulation tests that attempt to anticipate how autonomous vehicles would react in millions of driving scenarios.

Engineers at the young simulation program were struggling to thoroughly test the company’s autonomous driving software, in part because of a lack of investment in the program, according to two people with direct knowledge of Uber’s autonomous vehicle unit. That stood in contrast to the process at Alphabet’s Waymo and some other major companies developing self-driving cars, where simulation testing was a top priority.

That is from The Information, which reports that Uber might have been better able to avoid collisions had it put more resources toward simulation tests. The failure to do that "stemmed from earlier decisions by the business unit and made worse by the growing pressure within Uber to move quickly to launch robo-taxis into the ride-hailing market by this year." Uber has yet to resume the public driverless car tests it suspended after a woman was killed crossing the street by ones of its cars in Tempe, Arizona, earlier this year.

Waymo, of course, has invested considerable resources in simulation testing, which it does with a virtual world called "Carcraft," after the popular game World of Warcraft. When The Atlantic profiled the program in August 2017, Waymo's virtual cars had already completed 2.5 billion miles:

At any time, there are now 25,000 virtual self-driving cars making their way through fully modeled versions of Austin, Mountain View, and Phoenix, as well as test-track scenarios. Waymo might simulate driving down a particularly tricky road hundreds of thousands of times in a single day. Collectively, they now drive 8 million miles per day in the virtual world. In 2016, they logged 2.5 billion virtual miles versus a little over 3 million miles by Google’s IRL self-driving cars that run on public roads.

In the meantime, while Uber is being written up for neglecting simulations that may have averted a pedestrian death, accidents involving Waymo continue to be ruled not Waymo's fault:

One of Waymo's self-driving development vehicles, presumably a Chrysler Pacifica, was involved in a multiple-car collision on Saturday night. An allegedly impaired driver ran a red light at Country Club Drive and Southern Avenue in Mesa and collided with the Waymo vehicle. The driver then continued and collided with three other vehicles before being arrested after first responders arrived.

The short-term risk to Uber is that it's forced to put the brakes on self-driving car development, a program that at least Travis Kalanick felt was "existential" to the company's survival. The long-term risk is that cities where self-driving cars would logically deploy shy away from working with Uber, scared off by both potential harm to citizens and the reputational damage to their careers. The other long-term risk is that Uber develops such a bad brand on safety that once self-driving cars go mainstream, most consumers don't want to get into an Uber vehicle. Waymo may have set the narrative up at trial, but Uber is the one playing it out.

Other stuff.

Uber experiments with letting riders wait longer for a cheaper fare. Argo AI lures talent from Apple and Uber. Hipcamp raises $9.5 million led by Benchmark. Farmer-friendly grocery service Farmdrop raises £10 million. RideOS raises $9 million for autonomous vehicle routing software. Didi Chuxing launches in Australia. Lyft Expands Driverless Car Service in Las Vegas. WeWork discloses $1.5 billion revenue run rate for first quarter. Chicago expands fleet of electric buses. Google Maps removes Uber integration. GM has no projects underway with Lyft. Airbnb partners with NAACP to get more people of color renting homes. Chicago considers home-sharing surcharge to fund domestic violence shelters. Boston tightens rules for Airbnb. Taiwan cracks down on short-term rentals. We're running out of delivery drivers. Seniors miss taxis. 139 taxi medallions sell at auction for $24.2 million. Taxi worker advocates plead for regulation after sixth driver suicide. New Yorkers spurning public transit for ride-hailing. Ride-share passengers can buy their own insurance. Uber hires cricket superstar. Airbnb Bans Teen Over "Out of Control" Party. Sally the Salad Robot.