NYC congestion pricing needs its Jane Jacobs

The MTA has done a terrible job selling congestion pricing to the public

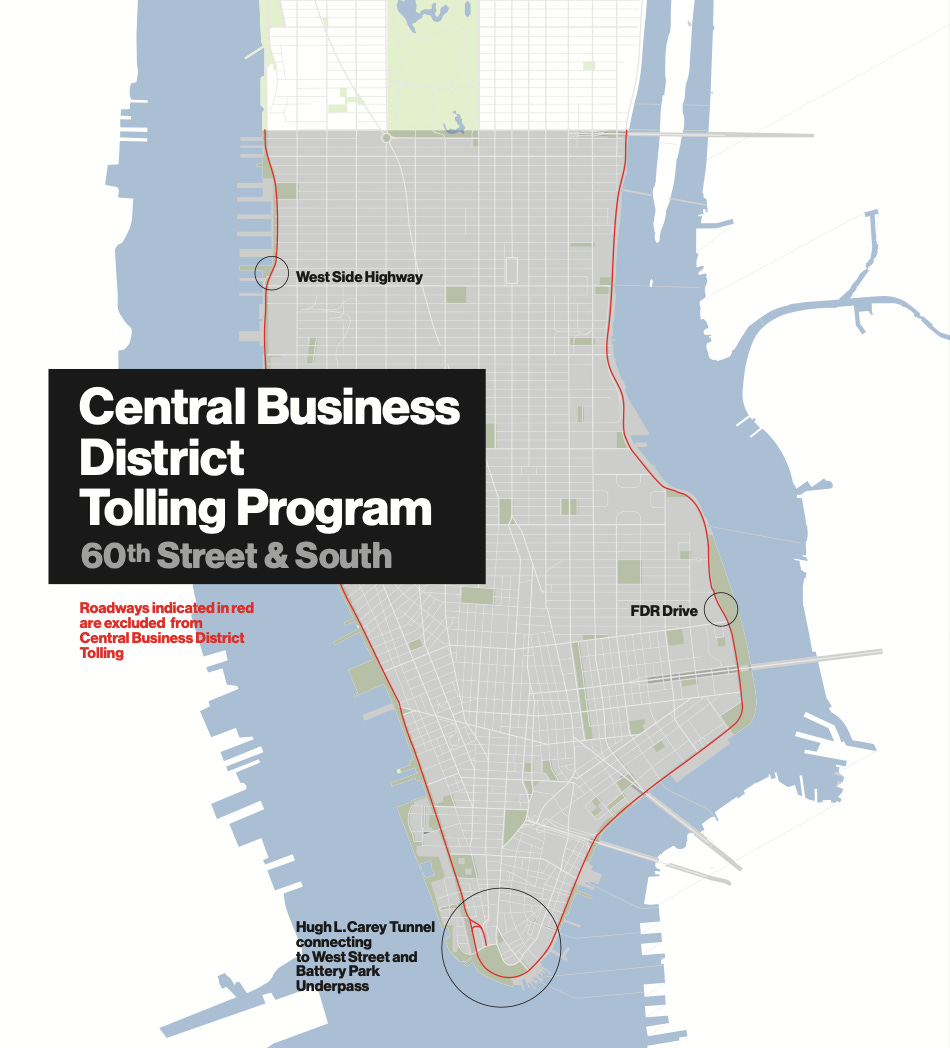

The New York City MTA is extending a public comment period on its congestion pricing plan for another two weeks, through Sept. 23, in response to “significant public interest” in the proposal. The Central Business District (CBD) Tolling Program will charge vehicles to enter Manhattan below 60th Street. It will be the first comprehensive congestion pricing program in the U.S., following the lead of global cities like Stockholm, Singapore, and London. While pretty much all the important details have yet to be determined, the plan is expected to bring in $1 billion a year, which the MTA will borrow against to fund its $51.5 billion overhaul of greater New York City transit. Eighty percent of revenue after operating costs will go to the city’s subway and buses, 10% to Long Island Rail Road, and 10% to Metro-North Railroad.

The MTA last week concluded a series of marathon public hearings on congestion pricing (one started at 5pm and finished shortly before midnight) that made clear exactly how controversial the program is. Americans have strong opinions about a lot of things, and cars and taxes are no exception. But what struck me as I watched an hour of the final hearing, on Aug. 31 (available here, if you’re so inclined), is that the MTA has also failed to lead a clear, compassionate, and compelling campaign on the case for congestion pricing.

The MTA officers overseeing the Aug. 31 hearing stared blankly from stock city-agency Zoom backdrops. The hearing opened with a 45-minute presentation on the tolling program, demonstrating an inability to explain the plan concisely or in a way that resonates with the average person. The opening slide of that presentation included an angry-looking orange-and-red map of the CBD and then chunky, poorly formatted text with dry phrases like “as defined in the New York State MTA Reform and Traffic Mobility Act” and “MTA 2020-2024 Capital Program.” It’s my job to find this stuff interesting, and after two minutes I was already bored.

Here are some other ways you might start that presentation:

Congestion pricing is a signature New York City investment in a better, more sustainable future

The Central Business District (CBT) Tolling Program will:

Make air cleaner for millions of New Yorkers

Increase average vehicle speeds in central Manhattan by reducing traffic

Fund improvements and modernization to the subway, buses, and commuter railways

Increase climate change resilience

Other global cities have implemented congestion pricing to great success, including London and Stockholm

It can be easy to dismiss the critics of congestion pricing who showed up to these hearings. Many were angry, concerned, and poorly informed, with wild claims about the MTA and New York City public transit. Opponents declared the plan “embarrassing,” a “money grab,” and a “war on cars.” Some called in from their cars. Some lived in New Jersey. Many were obviously there to say their bit and leave, rather than engage in a thoughtful discussion. But plenty of people also expressed thoughtful and legitimate concerns about the plan, and seemed confused and worried about what would happen. If the city has failed to effectively communicate the plan’s benefits and respond to those concerns, why shouldn’t they be?

One participant who stood out was Glenn Dewar, a lifelong Queens resident who spoke about his role as caregiver, first for his mother, then a partner who died of cancer during covid, and now for that partner’s mother. The current plans, he said, don’t consider people like him who need to care for disabled, elderly, or sick family members. “This program takes a lot of the best doctors and makes them inaccessible to people in the outer boroughs and any place else that need to drive a person in,” Dewar said. He also noted that during the pandemic his partner was immunocompromised, making public transit a high-risk transport option.

I find Dewar’s testimony compelling because it raises legitimate and difficult questions about congestion pricing, and also highlights the failure to anticipate and adequately address these concerns. As of now, the plan includes ‘mitigation and enhancements’ for low-income and disabled people, but it’s unclear what exactly that means. Elderly people with a qualifying disability can access the city’s paratransit services, but these have struggled with staffing and reliability. You can see why someone like Dewar would be concerned, and also imagine how CBD tolling threatens to put already expensive healthcare further out of reach for the people struggling most to access it. These problems are not insolvable—for instance, hospital visitors and patients could be able to validate their trips for a discount or exemption on the toll, similar to how you would validate parking—but solving them requires targeted engagement and commitment from the city.

Not surprisingly, lots of people want an exemption from congestion pricing. The list, according to MTA notes on the hearings, includes:

Hybrid, low-emission and clean-fueled vehicles

Medical hardship / hospital visits

Senior Citizens

Commercial motor vehicles

Charter buses

Commuter buses

Residents of the zone

Manhattan residents

Disabled population

Emergency vehicles

Low-income residents and non-profit agency vehicles

It can both be true that many of the groups on this list have valid reasons to want an exemption, and also that for the policy to work as intended, most of them can’t have one. We’re seen this already from the program’s first phase, which starting in 2019 imposed CBD surcharges of $2.50 on taxis, $2.75 on for-hire vehicles (FHVs, a category that includes ride-hail services like Uber), and $0.75 on shared rides. Without equivalent charges on other road users, the reduction in taxi and FHV trips was simply offset by a surge in other vehicles, like private cars and delivery trucks. If the goal is to dole out the smallest number of exemptions possible, then it becomes even more important that the public understand and receive consistent messaging about why congestion pricing is good and important. Anytime you threaten to take something away from people—in this case, free entry by car to central Manhattan—it’s better if you can also explain what they’re getting in return (say it with me: cleaner air, faster travel times, better public transit).

Arguably the community that most needs relief from congestion pricing is the South Bronx, which will experience an increase in truck traffic from drivers using the Cross Bronx Expressway to avoid the new toll. Protecting the Bronx from any adverse impacts of congestion pricing is a matter of environmental justice. Countless Bronx communities were torn apart by the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway in the 1950s and 1960s under Robert Moses. The legacy of that destruction has been borne primarily by low-income people of color. The Bronx is the poorest and least white New York City borough, with a population that is 29% Black, 56% Hispanic or Latino, and 51% low-income, and it already experiences some of the worst fine particulate matter pollution in the city. It’s important that the Bronx also benefit from cleaner air and a healthier environment, and not be asked to shoulder any negative externalities of a congestion policy.

The other group that has rallied hardest for congestion pricing relief is taxi and ride-hail drivers. The environmental impact report released in August warns that several tolling scenarios would increase the price of taxis and FHVs, reducing trips by up to 17% in the most extreme scenario. New York City taxi drivers have already experienced years of crisis following the arrival of Uber and Lyft and the collapse of the taxi medallion and can ill-afford another major shock to the market. Because the vast majority of drivers are low-income and/or immigrants, they are also considered an environmental justice population.

This latest phase of congestion pricing is perhaps the only time Uber and the taxi lobby have found themselves on the same side of an issue. Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, noted recently that taxi and FHV drivers are already paying the surcharges that took effect in 2019, and said higher fees “would lead to massive job losses for thousands and thousands of drivers in this city.”

Uber meanwhile supports congestion pricing, is a member of a coalition backing it, and spent $2 million on the issue, but landed in hot water with advocates last week for blasting out an email to customers that warned of “increased fees” and “transit deserts” and urged them to register their concerns with the MTA. The Uber missive claimed fees could reach $23 per trip for cars entering the CBD, which is true but only during peak hours in two of seven proposed congestion pricing schemes, making the message seem a bit fear-mongery, especially for a company that has previously endorsed the plan. The email also notably did nothing to reiterate the benefits of congestion pricing or any of the reasons Uber has previously supported it, further muddling the messaging around the issue.

I’m a fan of congestion pricing. I live in London, a city that has had a congestion charge since 2003 and which next year plans to expand the boundaries of another toll, the ULEZ, on vehicles that don’t meet low emissions standards. The combined effects of these policies are, frankly, remarkable. The air is cleaner. Average vehicle speeds are faster. Private car trips are down and, pandemic disruptions notwithstanding, public transport ridership, walking, and cycling are all up. In its first year, the congestion charge reduced traffic congestion by 30%. The ULEZ cut harmful nitrogen dioxide emissions nearly in half in its first 10 months, and London now expects to achieve legal pollution limits by 2025 that were previously expected to take 200 years. Without a doubt, these policies make my life in London safer, healthier, and better.

It’s not just me, a transportation policy nerd, who thinks this. Road pricing in London enjoys broad public support, thanks to public awareness campaigns that have focused on clearly explaining the schemes and emphasizing the health and quality of life benefits to all Londoners. Now more than ever, New York City needs to invest in doing the same: communicating clearly, concisely, and consistently why congestion pricing is in the best interests of New Yorkers. You can’t do that with dense hundred-page reports, stodgy 45-minute presentations, hearings led by stony faced officials, or lobbying from companies with checkered pasts like Uber. If New York is to unwind the legacy of Robert Moses, it needs a modern Jane Jacobs who can lead the way: meeting people where they are, making them feel heard, and, ultimately, rallying them around a congestion charge.