Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you're returning from last week, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! (Over)share the love and tell your friends to sign up here.

Pay to play.

Lyft and competitor Juno each filed lawsuits against New York City on Jan. 30 in an attempt to thwart new rules raising driver wages. Under legislation passed by the city in December 2018 and effective Feb. 1, ride-hail companies must pay drivers minimum per-minute and per-mile rates, such that hourly pay is at least $17.22 after expenses. The new pay rules were designed using a utilization rate that accounts for the share of time a driver spends completing rides compared to time spent idle and waiting for a fare. For more on that, see my full explainer of the utilization rate.

In its complaint, Lyft called the new pay rule “the product of arbitrary and capricious rulemaking” and argued it would fail to raise driver wages by depressing customer demand. Juno described the rule as “inherently flawed and fundamentally unfair” and alleged it would “destroy competition in the New York City market.” Lyft spokesman Adrian Durbin said in an emailed statement the pay standard would “advantage Uber in New York City at the expense of drivers and smaller players such as Lyft.”

The immediate response was chaos. In what became an elaborate game of telephone, everyone scrambled to figure out what everyone else was doing. Would Lyft and Juno be granted a temporary restraining order? If those two ignored the new pay standard, would Uber join the lawsuit too? Hearings were convened and incomplete information bandied about. New York City council member Brad Lander, who sponsored the ride-hail minimum wage bill, announced he was deleting Lyft. Adding to the confusion, an unrelated congestion pricing charge on for-hire vehicles in central Manhattan kicked in over the weekend, despite a separate ongoing lawsuit brought by the taxi industry.

As of now, here are where things stand:

A judge ordered Lyft and Juno to either pay drivers the minimum rates required by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission, or to pay the difference between the rates they paid and the rates the taxi commission asked them to pay into an escrow account on a weekly basis, beginning Feb. 8

Lyft told drivers it would increase earnings, effective immediately, “so you’ll earn the same amount that the TLC’s rules require.” Lyft won’t pay the new per-minute and per-mile rates, but plans to make up any difference in net weekly earnings with a “new weekly bonus” such that no money ends up in escrow

Uber said it would pay drivers the higher rates outlined by the taxi commission, which would likely reduce some promotions and eliminate others

Juno declined to comment

That these lawsuits came from Lyft and Juno, two companies that marketed themselves as better for drivers, is deeply ironic. There’s no easy answer to how to raise pay for ride-hail drivers in an open market where anyone can enter at any time. Raise rates and existing drivers will work more hours, new drivers will come online, and rider demand may fall on higher fares, meaning less work for everyone. See this paper (pdf) from a pair of Uber researchers and John Horton at NYU Stern (or my summary of it in Quartz). This problem is why the yellow cab medallion system exists in the first place. New York City created it in the 1930s because too many drivers were chasing too few riders, leading to long hours and unlivable pay. Cap supply with something like the medallion system, and wages can rise again.

Of course, over time the solution became the problem, with demand for cabs in New York City far outstripping the number of vehicles permitted by the medallion system. Enter Uber, and the tremendous popularity of app-based rides. Now there are more than 80,000 registered ride-hail vehicles in New York City, compared to 13,587 yellow cabs, the latter of which hasn’t changed in the last three years. In less than 10 years, we came full circle, and driver livelihoods were once again threatened by oversupply.

The pay formula the taxi commission adopted for ride-hail from economists James Parrott and Michael Reich isn’t perfect, but it’s pretty good. Instead of a rigid cap like the medallion system, it creates a dynamic one that accounts for supply and demand. The utilization rate is essential. Again, see my explainer for more on that.

Lyft and Juno would like you to believe this is about Uber. They allege these rules are designed to favor the dominant company, at the expense of smaller players like themselves. It’s hardly surprising they think that. Lyft and Juno have the two worst utilization rates in the industry, meaning their drivers have riders less of the time. But consider the complete utilization data and you’ll see Via, a shared rides company and the smallest industry player, scores best by far, evidence that the pay rules don’t only reward market dominance, as Lyft and Juno claim.

Similarly, as tech ethnographer Alex Rosenblat (check out her Uber book!) pointed out on Twitter, the new pay rules are a clear result of change in political will and sustained advocacy by pro-driver groups like the Independent Drivers Guild. It’s disingenuous to imply these changes were designed to bolster Uber.

Which brings me to the most important point: Lyft and Juno have effectively claimed that being forced to pay their drivers a living wage on each ride would put them at a competitive disadvantage. You can quibble over the details, but when you boil it down, that is the essence of the argument. How even to process that? In the old days, if you couldn’t afford to pay your workers in compliance with the law, chances were your company went out of business. Today when you can’t afford to pay your workers adequately you hire them as independent contractors through a “technology platform” and pay wages supplemented by just enough gamified incentives to keep workers coming back for more, like gamblers at the slot machines. The true innovation of Uber was figuring out the labor model that Lyft and Juno and so many other gig companies adopted. Now some of them can’t live without.

Eighty cents an hour.

Instacart paying workers badly is not new. Since Instacart started hiring regular people as shoppers to deliver groceries from stores to homes, the company has failed, at various points in time, to pay them a fair wage. Instacart has changed worker classifications, cut pay rates, cut tips, cut pay again, “mistakenly withheld tips,” changed pay structure, and generally, played enough games with wages to make a lot of its workforce very mad. But it takes a particularly egregious example, like one that happened last week, for any of those wage tricks to really blow up.

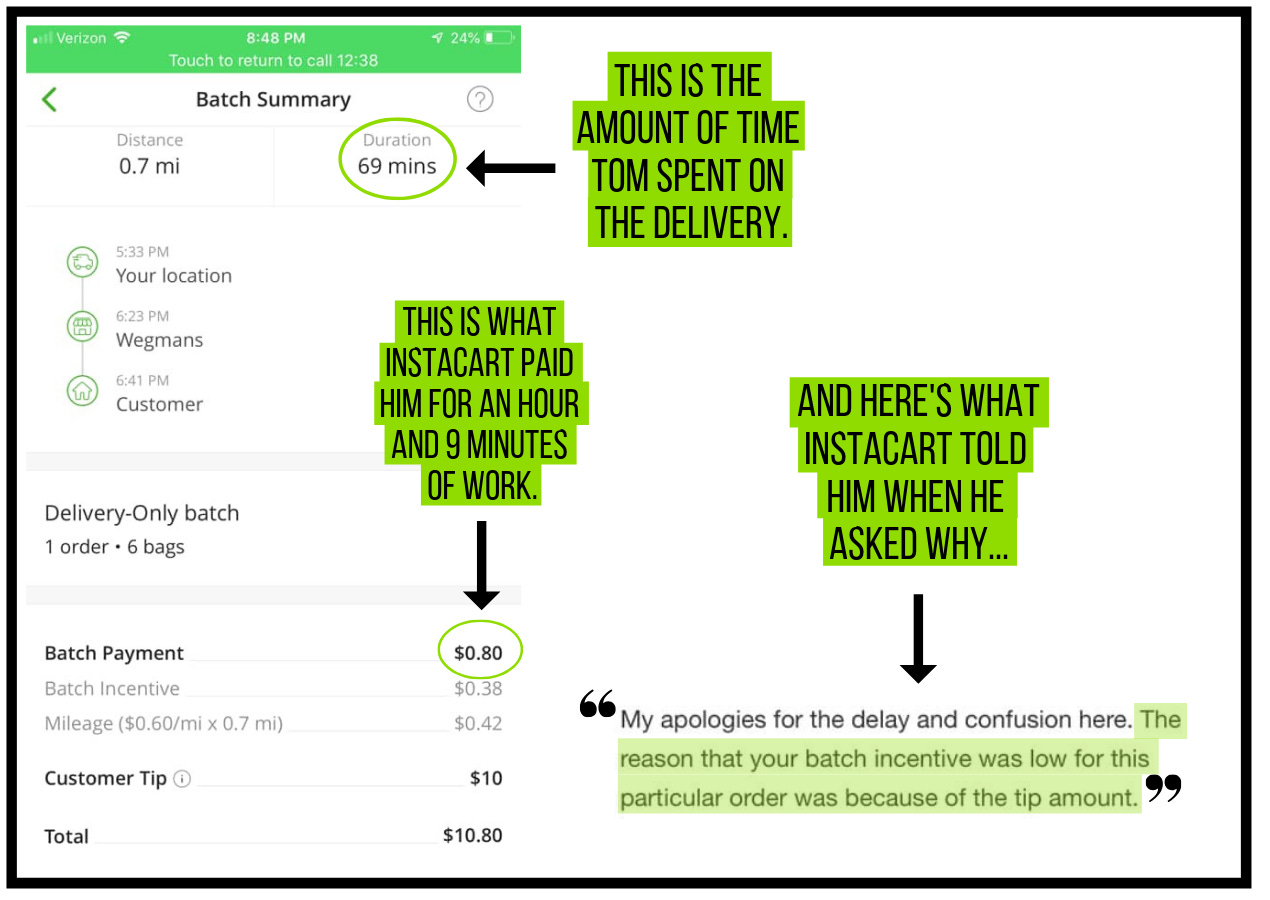

“Earn eighty cents an hour by delivering groceries with Instacart!” Working Washington, a labor rights group, posted online last week. The post included a provocative markup of an earnings receipt from an Instacart shopper, identified as Tom, showing the company paid him just $0.80 for 69 minutes of work. When contacted by Tom, Instacart rep “Brie C.” wrote back explaining his wages were low because the customer left a $10 tip on the order. From that reply:

My apologies for the delay and confusion here. The reason that your batch incentive was low for this particular order was because of the tip amount.

We include tips in the calculation so that you can get a more accurate picture of what your earnings will be after completing the batch.

Tips have always been included in our calculation of earnings and it helps provide a reminder to customers that you are providing a valuable service.

To summarize, Brie C. is saying that Instacart adjusted Tom’s pay to account for the tip left by his customer. The customer tipped $10, and so instead of adding that to Tom’s total pay, Instacart was like ok great, that’s $10 less we have to pay.

Because many Instacart workers are independent contractors, they aren’t protected by the same federal, state, and local wage laws as traditional employees. In Washington state, the minimum wage is $12 an hour. Washington also differs from many states in that it doesn’t allow tips or gratuities left by customers to be counted toward an employee’s overall minimum hourly wage (usually known as a “tip credit”). If Instacart shoppers were employees, what the company is doing would be very bad.

But Instacart are not employees. They are independent contractors conscripted through an app and subject to the algorithmic whims of the company, as with so many others in the gig economy. The technology-mediated aspect of the work also makes these workers particularly easy for companies to gaslight or otherwise disenfranchise, as Instacart knows well. The company played the incident off to Fast Company as an “algorithm glitch,” with chief financial officer Ravi Gupta telling the magazine, “despite the infrequency of these instances on the millions of orders that we fulfill, it’s one too many.” Gupta also threw Brie C. under the bus, telling Fast Company, “the information presented was not accurate,” and “we have to invest and continue to invest in better training and tools so that we get it right every time.”

Here is Alex Rosenblat again on Twitter:

The power structures of the gig economy make it incredibly difficult to prove when a company is doing something sketchy, with wages or otherwise. A company like Instacart can always claim that a guy like Tom is a glitch, an error, or some other abnormality that blames “the algorithm” while avoiding direct culpability. And who can prove otherwise? Instacart has all the data on wages and tips, not workers, labor activists, journalists, or anyone else. Dozens, hundreds, even thousands of examples collected painstakingly by a third-party can be brushed away with a comment noting that the examples represent only a small fraction of the deliveries Instacart shoppers complete. Data is always a trump card when only one side has access to it.

Uber oasis.

Vancouver, British Columbia, is one of the last metro areas in North America without Uber, Lyft, or another ride-hail service. Its public transit system is thriving:

So how have Vancouverites handled the lack of ride-hailing? Well, their city has hardly ground to a halt. The percentage of Vancouverites who commute to work by walking, cycling, or transit rose from 57 percent in 2013 to 59 percent in 2017. During that time, the share of commute trips by bicycle jumped by about 50 percent as Vancouver rolled out investments like a network of protected downtown bike lanes. TransLink, the regional transit authority, grew ridership by 5.7 percent in 2017, easily the fastest rate in North America. Andrew McCurran, TransLink’s director of strategic planning and policy, says ridership rose even faster in 2018, by 6.7 percent. Remarkably, a major driver was TransLink’s bus ridership, which rose by 7.3 percent last year.

Ridership on Vancouver public transit has grown even as 31 of the 35 largest transit systems in the US lost riders in 2017, and bus ridership fell by 5%. Those statistics haven’t stopped locals from wanting ride-hail services, or from frustrating tourists who aren’t able to get an Uber when they travel. Meanwhile just 10 years into the Uber era, some people are already longing for the past.

Driverless angst.

Waymo’s self-driving cars aren’t being attacked only in Chandler, Arizona. The Phoenix News Times reports that they have also been harassed in neighboring Tempe, where an Uber self-driving car fatally struck a woman in March 2018:

Two days after an Uber driverless car hit and killed a pedestrian in Tempe, someone used their own vehicle to try to run a Waymo vehicle off the road.

It was about 7:20 p.m. on March 20, near Priest Road and Southern Avenue in Tempe. The Waymo driver, identified in a police report only as "Anthony," said a dark-gray, later-model Toyota Camry was tailgating him and driving "all over the lanes." As Anthony drove north on Priest and turned left onto Southern, the other car tried to force him off the road, he told Tempe police.

Per documents obtained by the Phoenix News Times under public records requests, Waymo vehicles have been attacked, stalked, or harassed in Tempe multiple times. In a June 2018 incident, Waymo’s female safety driver reported an “unknown male suspect” recklessly tailing her in a beat-up white PT cruiser. The safety driver, Ashley Velmarie Anderson, also reported the man brandished a foot-and-a-half long pipe at her, and pointed his hand in a gun shape toward his glove compartment. In another incident, a man holding a boulder brought a Waymo vehicle in autonomous mode to a sudden halt when he jumped in front of it and motioned as though to throw the rock he was holding through the passenger window. Just wait until these things are everywhere.

This time last year.

Travis Kalanick wanted a "pound of flesh" when Uber bought Otto

Other stuff.

Grab raises $200 million from Thailand-based retail company. Deliveroo couriers protest new scheduling requirements. South Korea gig workers seek bargaining rights. Better Gig Economy Jobs Are Good for Business. Google hired gig workers to build out AI for defense department contract. Lime scooter rider fatally struck by Uber driver. Family of woman killed by self-driving Uber sues Tempe, Arizona. Ride-hail companies suspend service in Barcelona. Uber had little impact on traffic deaths in South Africa. 2nd Address raises $10 million to compete in business travel market. Uber offers speedboat rides in Mumbai. PeaPod picks Deliv for same-day delivery test. Blue Apron rolls out meal kits for Jet.com. Postmates being kept afloat by Kylie Jenner. Uber tests adding public transit to app. Airbnb pledges $2 million for homeless youth. Florida considers sanctions on Airbnb over West Bank policies. Tel Aviv to double municipal tax on Airbnb rentals. Coursera launches self-driving cars class. Lyft driver arrested for sexual assault. “This whole thing is a big Texas-sized whodunnit.”

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can forward it or suggest they sign up here.

Send tips, comments, and shopper secrets to @alisongriswold on Twitter, or oversharingstuff@gmail.com.