Lyft has drivers, Uber has earners

"Increasingly we want earners to earn, however they want to on a particular day"

Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. This is a subscriber-only post. To get the full post and more in-depth analyses of mobility and the gig economy, become a paying subscriber.

The post-pandemic challenge for both Uber and Lyft has been getting drivers back online. Drivers ditched ride-hail platforms en masse during covid, some opting for jobs that came with benefits like sick pay and health care, and others preferring to transport food or groceries rather than people. The driver shortage increased ride wait times and drove up prices. Getting a ride in 2021 was “next to impossible” or “almost impossible”; fares were “astronomical.”

Uber set aside $250 million for driver incentives in April 2021 and has been busy partnering with taxi companies to increase its ride supply. Lyft has also spent heavily to get more people driving, to the dismay of analysts on its first-quarter earnings call this week. Chief financial officer Elaine Paul said Lyft spent $350 million in the first quarter on “incentives classified as contra [revenue],” a category that includes driver subsidies, 3% more than in the same period last year. Lyft plans to continue the subsidies for now, Paul added, weighing on Q2 margins. “This is an investment quarter,” she said. “When the marketplace reaches much healthier balance would be hard to predict.” In other words: we don’t know how long we’ll need to keep subsidizing drivers to have enough on our platform.

Uber also got some questions about driver supply during its earnings call the following day, but the tenor of the discussion was different. Asked about incentive pay and the challenges at Lyft, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi reiterated that Uber started investing heavily in driver supply last April, both with incentives and improvements to its signup process. “We have pivoted the company to being earner-centric, innovating for earners, thinking about the earner experience, treating earners as you know with respect and dignity and building for them versus building just for the company,” he said.

I recall Uber’s campaign to focus more on drivers, but seem to have missed the pivot to ‘earners,’ a term that cropped up 19 times on Uber’s call, just one time fewer than ‘drivers.’ “We don’t necessarily look at earners now as couriers or drivers because increasingly we want earners to earn, however they want to on a particular day,” Khosrowshahi said.

This is the clear advantage Uber holds over Lyft as both companies attempt to stabilize the labor side of their platforms: Lyft has drivers, Uber has earners. Both companies offer flexible work in the classic gig economy sense (choose your own hours, be your own boss), but Uber has the added benefit of variety. You can choose each day whether you want to move people or things.

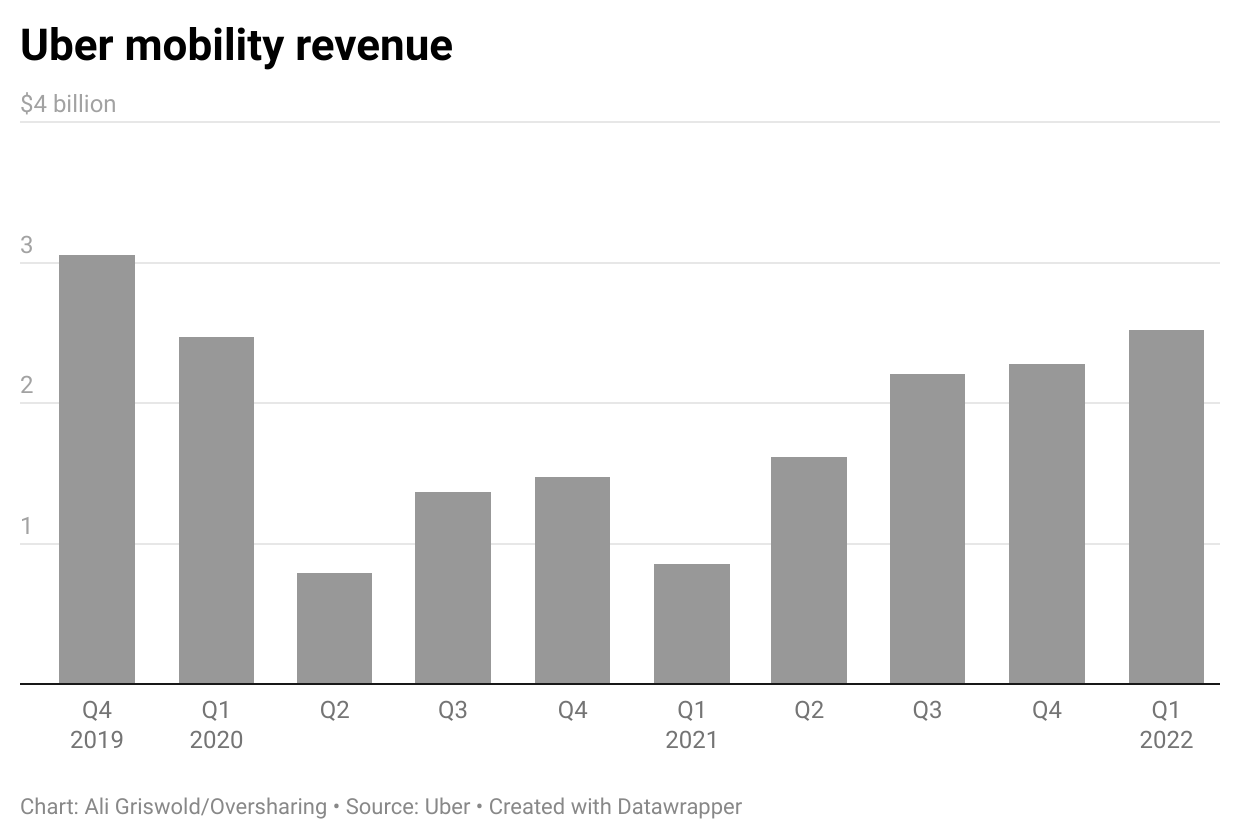

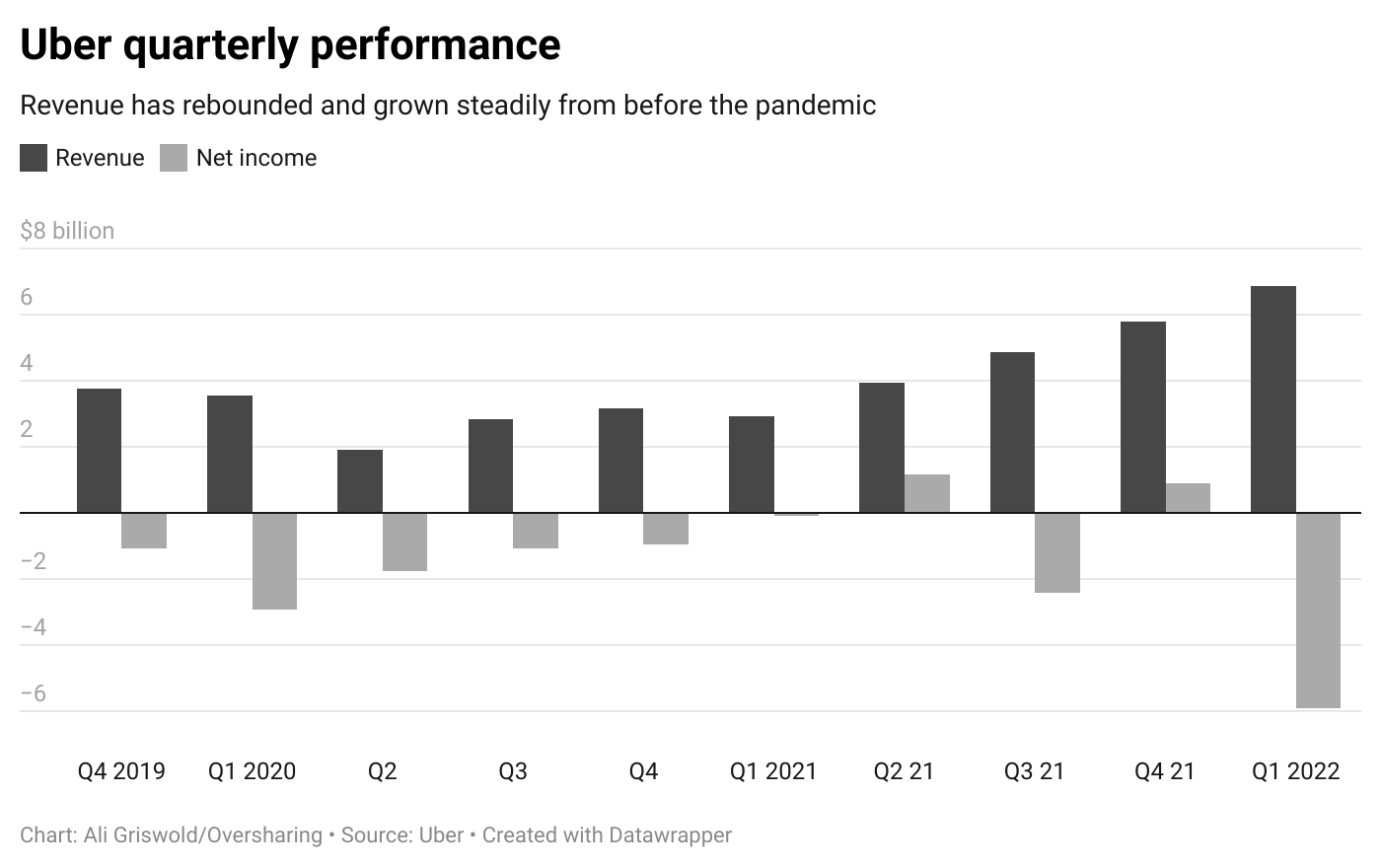

This might also explain why Uber lately seems to be faring better in its covid recovery than Lyft. Granted, both companies are still losing money. Lyft lost $197 million in the first quarter. Uber reported a whopping $5.9 billion net loss after the value of its stakes in Grab, Aurora, and Didi cratered. But Uber has now posted five consecutive quarters of revenue growth, while Lyft’s revenue fell from the fourth quarter of 2021 to the first of this year, a dip execs blamed on the omicron variant hitting demand hard in January. Year over year, Uber’s revenue grew 136% in the first quarter compared to 44% at Lyft, and revenue from Uber’s ‘mobility’ segment jumped 195%. Uber attributed the strong growth in mobility (read: rides) in part to a recovery in airport bookings (13% of rides in Q1 2022, up 166% from Q1 2021), better than at Lyft where airport rides made up 8% of bookings in the first quarter.

Diversifying the labor side wasn’t always a strength for Uber. Back in the Travis Kalanick era, Uber at times struggled to balance the needs of rides, Eats, and the now defunct Rush courier service. There was even a period where drivers switching from rides to food deliveries around dinner time would cause surge pricing on the ride-hail platform, one former Uber employee told me back in 2017, bringing new meaning to the dinner rush.

The pandemic was the first time when Uber’s edge from moving into deliveries of food and groceries really became clear. As the world went into lockdown and revenue from rides evaporated, Uber’s delivery segment surged and rapidly became the biggest part of the business. The latest quarter was the first since Q4 2020 when mobility generated more revenue than delivery, and only by the narrowest of margins. It turns out that when a deadly virus strikes, delivery is a great business to be in.

Covid proved the demand-side benefit of Uber being in rides and delivery. The pandemic isn’t over, but as many people choose to return to something like normal life, what we’re now seeing is the supply-side benefit of Uber having multiple lines of business. If you believe Khosrowshahi—and in this case, I do, especially when you compare Uber’s results to Lyft’s—being able to court ‘earners’ instead of ‘drivers’ is a big advantage in rebuilding the worker side of the platform. Uber’s CEO pointed out on the earnings call that ‘earner’ retention and engagement are both improving. He also noted that because of regulations and background checks, it can be quicker to sign someone up on Uber as a delivery worker than as a ride-hail driver.

“On the backend, as it relates to earners, we are a single super app,” Khosrowshahi said. “And essentially you sign-up to earn on Uber and more and more, we will offer you different opportunities to earn based on what we know about your profile, based on time of day, based on where you are and based on what the opportunities are. And we think that’s a very, very significant structural advantage over other players in our industry.”

The problem with two-sided platforms is that they are two-sided. On the consumer side, only so much differentiates an Uber ride from a Lyft ride, which is why a lot of people will just check both apps and take the cheaper option. And so the business is arguably won or lost not on the consumer side but on the worker side. This explains why ride-hail companies have historically poured so much money into bonuses and incentives for drivers, in an effort to have the stronger labor pool, but these sorts of subsidies aren’t sustainable in the longterm. If Uber can get ahead of Lyft not with incentive pay but with a more appealing pitch as a platform for ‘earning’ rather than ‘driving,’ that would be a very big deal.

Nice synopsis clearly delineating the two different approaches.