Quick book note: I finished reading Evicted by Matthew Desmond this weekend and can’t recommend it enough. Tragic, compelling, and deeply informative.

Public-private transit.

Uber is rushing headlong into public transit partnerships and pseudo-public transit offerings. In Philly, Uber is pitching in $1 million to help the city tackle delays and overcrowding on SEPTA, its public transit system. In New York, Uber for July and August is offering unlimited UberPool “commute cards” at rates cheaper than the New York City subway. In DC, the city’s fire and EMS departments are thinking about using Uber-like services to transport 911 callers who need to get to a doctor but not an emergency room. And at the federal level, lawmakers are pushing for a bipartisan bill that would allow federal government employees to apply their public transit subsidies to ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft, as well as bike-rental programs like Capital Bikeshare.

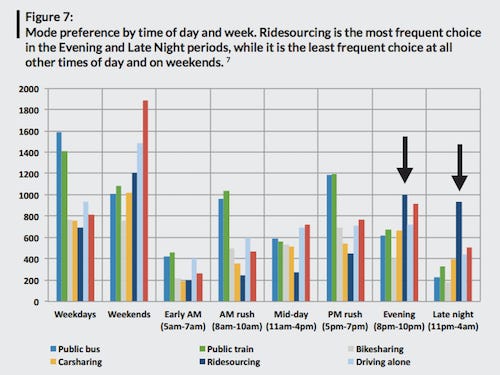

The push into public transit is another way that Uber, which began as “everyone’s private driver,” has tried to democratize its ride-hailing service and soften its image. The company got a strong endorsement on this front in March, when the American Public Transportation Association found that people who used ride-hailing services were also more likely to take public transit and own fewer cars, and recommended that cities work with Uber and its peers to “improve urban mobility.”

SF gigs.

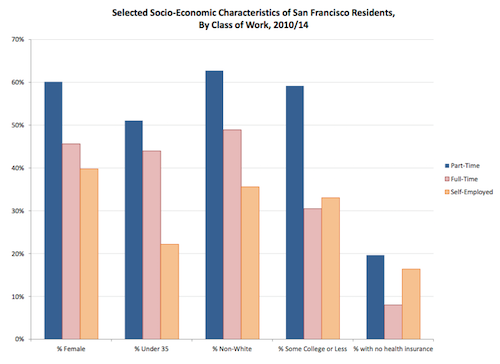

San Francisco’s chief economist last week released a report asking whether it is “fair to call San Francisco a leader in the gig economy?” The real answer seems to be “we don’t know” but the report is full of charts and local employment statistics anyway. For example: San Francisco has a smaller percentage of residents who are part-time employees than the state or country, but more who reported being self-employed. In transportation and manufacturing, self-employment has grown much faster than full-time employment over the last 10 years. Self-employed workers in San Francisco are also more likely to be male, white, over 35, and well educated.

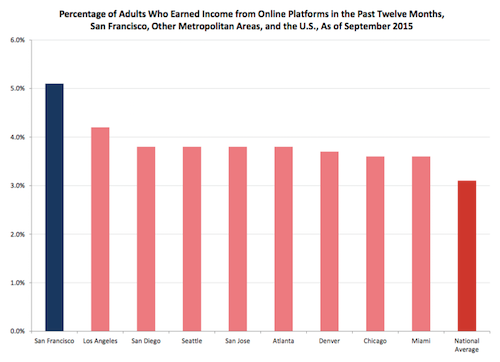

On the gig economy question specifically, the best data SF has comes from research done by the JPMorgan Chase Institute, which estimates that 5.1% of adults in the Bay Area earned at least some income from online platforms as of September 2015. That’s higher than in most other metro areas, but still a small fraction of the workforce. “Online platforms have had relatively little role in shifting people from full or part-time work into self-employment, and are not enabling a wholesale shift from wage work to a ‘1099 economy,’” the report concludes.

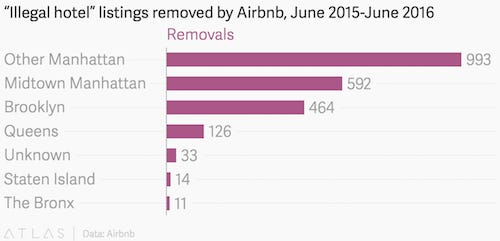

2,233.

That is the number of New York listings that Airbnb says it removed over the last year as it makes a last-ditch attempt to dissuade the state from enacting regulations that could cripple its business. “We have acted on a one host, one home policy in NYC and have taken down 2,233 listings that appeared to be hosts with multiple listings that could impact long term housing availability,” the company wrote in a release last Thursday (July 7). “We are concerned about hosts who may offer space that could otherwise have been on the long-term rental housing market in New York City.”

Airbnb has rarely, if ever, struck such a conciliatory tone in New York, which seems like the best indication that the company is genuinely panicked about the short-term rental bill awaiting a signature from the governor. The bill, passed by the state senate last month, would make it illegal to advertise short-term home rentals online. (Short-term rentals themselves, i.e., those lasting less than 30 days, are already illegal under New York state law.) Airbnb’s vocal opponents on New York City council are pushing hard for Cuomo to sign the bill. Airbnb, meanwhile, has rushed to clean up its listings to make the service appear more attractive and law-abiding. (It also set up a New York PAC.) As of June 1, 2016, Airbnb claims that 96% of its hosts in New York City who rent out their entire unit have only one such listing.

Illegal eats.

Here is a good story from Sarah Kessler at Fast Company about startups that use online marketplaces to help home cooks run small-scale catering businesses. The food is local, artsy, and delicious. Also, quite possibly illegal.

Most states—with some exceptions for baked goods, granola, and other "non-potentially hazardous" products—require that food sold to the public be cooked in a commercial kitchen. In California, the retail food code specifically lists home kitchens as a place where commercial food facilities cannot operate. But that has not stopped food startups like Josephine from bringing food into the sharing economy.

Josephine, a tiny operation in the Bay Area, had signed up about 75 cooks this spring when the health department moved to shut it down. Health officials delivered cease-and-desist letters to about a dozen Josephine chefs, with charges that included “facilitation” and “aiding and abetting.” “My first thought was, ‘I committed a crime,’” says Renee McGhee, a 59-year-old grandmother who cooked for Josephine and got one of the crease-and-desists. “It felt icky.”

Other stuff.

How Uber Secretly Investigated Its Legal Foes—and Got Caught. Jeb! spends big on Uber. UberEats “discernibly bad news” for Deliveroo in London. UberEats coming to South Africa. Uber plans August launch in Montana. Uber uses bitcoin debit card to bypass roadblock in Argentina. Lyft adds luxury service. What tech employees really think about tech-shuttle “hubs.” Early Zenefits investors are doing just fine. The Myth of the Millennial Entrepreneur. Most Mechanical Turkers are young college grads. HourlyNerd raises $22 million. Leveraged loans. Eagle 1. International ice cream day. Didi price hike. Didi angel. Uber bot. Man’s New Best Friend Is a Goat.