Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy.

If you're returning from last month before I went on vacation, thanks! If you're new, nice to have you! It is nice to be back, especially since *absolutely* *nothing* *happened* while I was away. Let's jump back in. This is issue ninety-eight, published April 3, 2018.

The first death.

Anthony Levandowski finally got something he wanted.

"I'm pissed we didn't have the first death," Levandowski, Uber's former head of autonomous vehicles reportedly told several Uber engineers in 2016, after a Tesla driver died in a fatal crash while using the car's "autopilot" technology. Levandowski, a man of questionable judgement, reportedly interpreted the Tesla incident as confirmation that Uber's self-driving team wasn't pushing aggressively enough.

Well, good news, Anthony! Uber can now lay claim to a first death of its own. On March 18, an Uber-operated self-driving car struck and killed a pedestrian crossing a street at night in Tempe, Arizona. It's believed to be the first pedestrian death to result from self-driving technology.

Video footage released by the Tempe police department shows Uber's car, which failed to slow, coming up on Elaine Herzberg, 49, as she crosses the otherwise empty road with her bike at night. An interior view shows the vehicle's "safety driver," a human monitor, looking down away from the road until moments before impact.

Further reporting revealed that Uber had disabled the standard collision-avoidance technology in the Volvo SUV that struck Herzberg, and reduced the number of lidar units on its latest generation of autonomous vehicles, leaving the cars with a roughly three-meter blind spot where a pedestrian might be. Its cars struggled to travel 13 miles without a human intervention, compared to the average of nearly 5,600 miles the cars operated by Waymo in California could go unassisted as of last year.

Uber has since suspended driverless car testing in Tempe, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, and Toronto, and said it won't reapply for a testing permit in California, where its license expired March 31. Last week Uber settled with Herzberg's husband and daughter for an undisclosed (but probably very large) amount.

In a letter to Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi that called the event "an unquestionable failure" and "disturbing and alarming," Arizona governor Doug Ducey suspended Uber from testing its cars on public roads. But Ducey was complicit. It was Ducey, after all, who welcomed Uber "with open arms and wide open roads" after the company defied regulators in California and got its driverless vehicle registrations revoked. It was also Ducey who in 2015 established Arizona's loose autonomous vehicle regulations, signing an executive order that directed state agencies to "undertake any necessary steps to support the testing and operation of self-driving vehicles" on public roads. Ducey and Uber reportedly maintained a cozy relationship that included his appearing at various Uber events and plugging the company on Twitter at its request.

We saw similar events play out last year in Pittsburgh. No one died, yes, but that was another case where the city initially bent over backward to accommodate Uber, then became disillusioned when it became clear that the company had little intention of returning the favor. Like Ducey, mayor Bill Peduto supported Uber at events and had a chummy rapport with its executives (he and Travis Kalanick texted). The state of Pennsylvania gave it a long leash to operate. Only after public sentiment turned against Uber did Peduto also change his tune, saying, "this is a two-way street, not a one way."

There are two failures here. One is by local governments, which, dazzled by promises of technology and job creation, have too often ignored safety concerns in the interest of "innovation." The other is by Uber, which got into driverless tech for competitive reasons and at many stages in the program—its hiring of Levandowski, hasty rollout in Pittsburgh, defiance of regulators in San Francisco, and testing in Tempe—has chosen competition over consumer safety. The reality is that Uber was glib on safety from the start. It didn't have an ethics board, and it declined to address who would be liable in an accident involving one of its self-driving cars, a question it deemed too hypothetical. Safety was a box to check, not a real concern, and those choices are hard to untangle. Now Uber has to live with that.

Plight of the safety driver.

A side narrative to come out of the Uber crash in Tempe was that of the "safety driver," a human who sits behind the wheel of a self-driving car and monitors its progress, ready to seize control at any moment. Honestly, it sounds completely terrifying:

With their hands loosely around the steering wheels and right feet at the ready, test operators are trained to take control and swerve or hit the brake when their robot cars act erratically or encounter something unexpected, say current and former operators for Uber Technologies Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s Waymo.

That means a need for constant vigilance over the course of a typical eight-hour shift, they say, even though the cars navigate streets unaided most of the time.

"The computer is fallible, so it's the human who is supposed to be perfect," one former Uber test driver said. "It's kind of the reverse of what you think about computers."

CityLab spoke with former Uber safety driver Ryan Kelley, who said he and his fellow drivers saw a fatal crash coming. Kelley said he felt pressured to collect miles and skip breaks, even though Uber never gave him explicit mileage goals. He found it hard to maintain focus for hours on end since he wasn't actually engaged in driving the car most of the time.

I'm reminded of a section in Tim Harford's Messy, where he posits that maybe we're going about autonomous vehicles wrong. The problem, Harford argues, is that until we have fully self-driving cars, humans will be expected to handle any number of "edge case" scenarios while also being lulled into a false sense of security by the autonomous vehicle. He compares it to the pilots on Air France Flight 447, who stalled an Airbus 330, killing everyone on board, because they couldn't fly it when the autopilot failed:

…when the computer gives back control to the driver, it may well do so in the most extreme and challenging situations. The three Air France pilots had two or three minutes to work out what to do when their autopilot asked them to take over an A330; what chance would you or I have when the computer in our car says "Automatic Mode Disengaged" and we look up from our smartphone screen to see a bus careening toward us?

Automated systems reduce the likelihood of routine problems, but when something does go wrong, it's often catastrophic. Instead of creating automated systems that let humans disengage, Harford thinks maybe we should design technologies that help humans sharpen their skills and stay alert:

Rather than let the computer fly the plane with the human poised to take over when the computer cannot cope, perhaps it would be better to have the human fly the plane with the computer monitoring the situation, ready to intervene. Computers, after all, are tireless, patient, and do not need practice. Why, then, do we ask the people to monitor the machines and not the other way around?

Meanwhile, we still need people in autonomous cars for when cops give the vehicle a ticket.

You get five stars!

Have you ever given a driver five stars even though the ride wasn't great? I assume if you've ever taken any ride-hailing service, the answer is yes. Uber's ratings system is deeply messed up. Because Uber regards drivers as independent contractors, it can't explicitly tell them what to do, so it uses ratings as a sort of proxy. Uber sets a minimum threshold and drivers who fall below it risk "deactivation," platform-speak for being fired. Because that minimum rating is pretty high, drivers can really only afford to get—and riders to give—five-star reviews (the scale is one to five).

The problem is so bad that one Lyft driver in California last year posted a translation of the ratings system in his car, with four stars defined as "This driver sucks, fire him slowly." In July, Uber said it would make riders add an explanation when they rated a ride less than five stars.

How did it get this way? That's the topic of a new paper, "Reputation Inflation," from NYU's John Horton and Apostolos Filippas, and Collage.com CEO Joseph Golden, which posits that "reputation systems, as currently designed, sow the seeds of their own irrelevance," a wonderfully punchy line by any standard, and remarkably so for an econ paper.

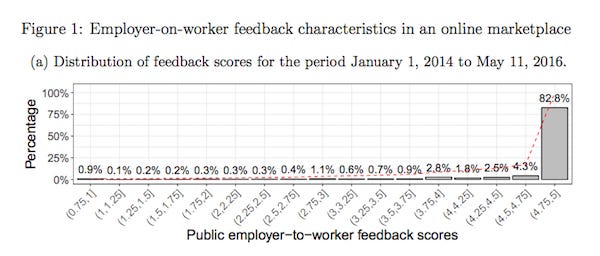

The online ratings landscape is inflated beyond Uber. A 2015 paper found that the median seller on eBay had 100% positive feedback ratings and the tenth percentile had 98.21% positive ratings. The average "public" rating on the platform featured in the study from January 2014 to May 2016 was 4.77 stars, on a scale from one to five.

"Public" in this case means the rating left by the person using the service (the "employer") is visible to the person providing the service (the "worker"). The other type of feedback is "private," meaning reviews and ratings employers were asked to provide that weren't shared with the worker or future potential employers, an option introduced in April 2013. The paper doesn't name the platform, but some quick googling of details in the analysis, plus the job history of co-authors Horton (former staff economist at oDesk, now UpWork) and Golden (former staff and consulting economist at Upwork) suggest that it is almost definitely Upwork.

Some observations from that platform:

Most people leave reviews. Over the history of the platform, 82% of employers who could leave feedback did.

Inflation sets in over time. In its 10 years of operation, the average score has increased by about one star (3.74 to 4.85). About half of that happened in 2007, when the average rose by 0.53 stars.

People who leave negative private feedback still give publicly positive reviews. During the studied period, about 15% of employers left "unambiguously bad private feedback" but only 4% gave a public rating of three stars or less.

People are more candid in written comments than in numerical scores. The authors suggest this is because it's harder for workers to complain about "textual tone" than a "non-perfect star rating," and also harder for future employers to read qualitative feedback and hold it against those workers.

So what's up? The paper argues that online platforms, especially peer-to-peer ones in which transactions occur directly between two people, experience ratings inflation if the cost of leaving a bad score increases over time. This cost could take different forms: it could be that the person leaving the review fears retaliation for a bad score, or that she's worried about harming the ill-performing worker. The second rationale is often the case on Uber, where savvy riders know a less-than-perfect score could endanger their driver's daily livelihood. Thus, imperfect scores are reserved for extreme scenarios like hostile conduct or reckless driving.

This theory was borne out by the examined platform's decision in March 2015 to release private ratings in batched feedback scores for workers. In other words, leaving a negative review in private suddenly carried a cost. The result was immediate: private ratings increased, bad feedback became scarce, and "what was mildly negative before became very negative." At the studied rate of inflation, the authors estimated that the average private feedback would reach the highest possible score in seven years.

The problem is obvious: the more consequential ratings are, the less informative they risk becoming. The dynamic is particularly acute in on-demand and "sharing" economy platforms "where both wage penalties for workers and employers' reflected cost coefficients are high." By tying employment status to ratings, companies force users to make tough managerial choices so they don't have to. The researchers suggest that this is ultimately a more powerful motivator for users than fear of retaliation: "reflected costs are due to raters incurring a greater personal cost—or guilt—the greater the harm they impose on the rated worker." Put another way: on-demand platforms are offloading their guilt onto you. Five stars all around!

Sunk.

Uber but-for-taking-your-stuff-to-the-post-office startup Shyp shut down, and honestly it's about time. The company raised $63 million to take the hassle out of shipping, with an app that summoned a courier on-demand to whisk away your package for the low price of $5. The business plan was large-scale shipping arbitrage but the economics turned out to be (shock) not favorable:

Shyp’s goal had never been to build a business on $5 pickups. Instead, it was able to negotiate deep discounts from companies such as Fedex and UPS and then mark up the delivery cost it charged its customers, allowing for a significant theoretical profit margin. But it began recalibrating its operations to make sure the service it offered for $5 didn’t destroy its ability to make money via shipping-cost arbitrage. For example, it decided to charge for packaging, which now starts at $3 an item and can cost up to $75 for an extra-large, fragile item. (It also started letting you opt to do your own packing, which isn’t magical at all.)

Hm, an on-demand company that, after its original unit economics didn't work out, tried to keep advertised costs low while fattening up its margins with extraneous fees… where have we heard that one before? Anyway, Shyp co-founder Kevin Gibbon is sad and sorry:

My early mistakes in Shyp’s business ended up being prohibitive to our survival. For that, I am sorry. I’m sorry to the world-class team who joined me on this journey—together, we boxed so many shipments that we could’ve blanketed San Francisco with cardboard 4.5 times. I’m sorry to the hundreds of thousands of customers who validated our idea by shipping enough packages to circle the earth half a million times over. I’m sorry to all of the investors and partners who have always rooted for us, and whose advice I sometimes ignored.

Also that is a lot of cardboard, maybe he should add the environment to the apology list.

Other stuff.

Uber sells Southeast Asia business unit to Grab. Singapore watchdog says Uber-Grab deal may be anticompetitive. Uber for helicopters startup Blade raises $38 million. CTO of GM's Cruise leaves after complaints from female employees. Otto co-founder Lior Ron leaves Uber. Nvdia suspends self-driving tests after Uber crash. Uber to pay $10 million to settle discrimination case. Seattle considers raising Uber and Lyft rates. Berlin loosens rules around short-term rentals. Airbnb will disclose host information to the Chinese government. Lyft pledges equal pay for women and people of color. Ride-hailing hurting auto-rickshaws in Indonesia. Florida taxi company plans national ride-share push. New York adds "congestion" fees that favor shared rides. Behind-the-scenes vibes at Uber and Lyft. Alphabet's moonshot chief on regulating self-driving cars. Amazon Takes Fresh Stab at $16 Billion Housekeeping Industry. DC has never had more food delivery options. How Grubhub predicts your next order. Handy is lobbying state lawmakers to make its workers not employees. At Uber, a New CEO Shifts Gears. Meituan Dianping in talks to buy Mobike. China's bikeshare surplus, in photos. Elon Musk's April Fool's joke falls flat.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can suggest they sign up here. Send tips, comments, and five star ratings to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.