Flexible and adaptable assets.

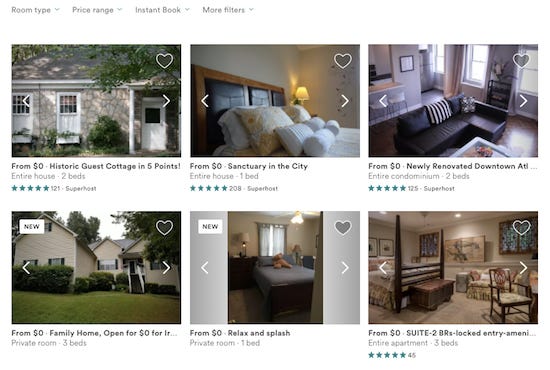

A few days before Irma made landfall in Florida, Airbnb activated its disaster response program in the panhandle, northern Georgia, and parts of South Carolina, encouraging hosts to list their homes for free and inviting evacuees to seek shelter through its peer-to-peer platform. Uber said it would cap fares in south Florida such that no one got “an outrageous, higher-than-usual price.” Elon Musk unlocked the full battery life of Tesla’s 2016 Model X and Model S vehicles, so that drivers attempting to evacuate could get further on a single charge. Facebook activated Safety Check. After Irma changed course, Uber and Lyft offered free rides to shelters near Tampa, publicized through the local office of emergency management.

Meanwhile, in Florida and over in Harvey-ravaged Houston, Texas, people downloaded walkie-talkie app Zello to become makeshift first-responders:

I GOT a two-minute "training" session and a "good luck!" One of the key suggestions of the training session was that when I received a rescue request, I needed to try to call the person making the request if possible to get more details and to ensure that it was a legitimate request…

I took request after request after request. Name...phone number...address...number of adults...number of children...number of elderly...medical conditions. I would then type this information in as fast I could so the dispatchers could send the rescuers out. After submitting the information, I received an ID number that I was supposed to relay to the person requesting the rescue. We asked them to remember the number so they could give it to their rescuers when they were finally picked up. We could then mark them safe in the system, avoiding the dilemma of rescuers looking for people who had already been saved by someone else.

We are entering a new era in which the app-based technology that facilitates our transit, vacations, and social lives is also playing a serious role in disaster relief. FEMA, established in 1979, is still the first name associated with US disaster management, but crowd-based online communities are increasingly positioned to intervene in times of crisis. Airbnb has 4 million listings in 65,000 cities, a housing stock greater than the top five hotel brands combined. Uber has more than 2 million drivers and Facebook 2 billion monthly users.

These are vast and diffuse networks of people and resources that can be called upon with little more than a text, email, or push notification to a phone. Importantly, people underpin these platforms, not corporations. An Airbnb host in Austin doesn’t need to consult with multiple levels of management, as a hotel franchisee might, before opening her doors to a family of Harvey evacuees. They are also not professionals. A driver venturing near flood zones could be endangering themselves and their personal vehicle; a person who downloads Zello and plunges into a firehose of rescue calls, as Holly Hartman did, might not know what to do when a frantic caller reports that a family member has stopped breathing.

In an unpublished paper, currently under review, researchers at UC Berkeley describe the emergence of the sharing economy as “one of the most profound shifts in emergency transportation and sheltering policies.” They point to the nearly 400 Airbnb hosts who offered free housing after Hurricane Sandy—the origin of Airbnb’s current disaster response program—as well as the discounted trips Uber offered to and from Austin’s flood assistance center during flooding in 2015, and again in New Orleans during floods in 2016. “The overarching benefit of sharing economy resources (both transportation-related and housing-related) would be the addition of flexible and adaptable assets,” they write.

The tech world’s disaster response wasn’t always so polished. Uber enraged New Yorkers in October 2012 by doubling prices during Hurricane Sandy, and again the following year when surge rose to 7x during a heavy snowstorm. It came under fire in 2014 in Australia for turning surge pricing on as people fled a hostage situation in downtown Sydney. Facebook has had plenty of mishaps with its safety check feature. Uber’s policy of capping fares during disasters and emergencies came about not because Uber had a change of heart, but through an agreement with the New York state attorney general.

Uber, Airbnb, and other sharing economy apps are no substitute for federal and professional disaster relief, but as the Berkeley researchers say, their “flexible and adaptable” assets are an interesting complement. For companies like Uber and Lyft that are hashing out a variety of public-private partnerships—products that resemble a bus and government-funded rides for areas historically underserved by public transit—offering to work with local officials on emergency planning also might help sweeten those deals.

Hell.

Elsewhere in Uber, the company is facing an FBI probe over a program it used to monitor Lyft drivers:

Federal law-enforcement authorities in New York are investigating whether Uber Technologies Inc. used software to interfere illegally with a competitor, according to people familiar with the investigation, adding to legal pressures facing the ride-hailing company and its new chief executive.

The investigation, led by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s New York office and the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan, is focused on a defunct Uber program, known internally as “Hell,” that could track drivers working for rival service Lyft Inc., the people said.

Some companies insist on naming their projects the worst things. Uber’s roster includes Hell, greyball (to obscure operations from law enforcements), operation SLOG (also against Lyft), and God View (master access to user location and other info). Uber also had a War Room, which, in an effort to reform the culture, has since been renamed the Peace Room. Enron had the “Death Star” trade and mail-order pharmacy Philidor an “End Game LLC.” Parmalat, the Italian dairy and food corporation that engineered its financial statements, used a special vehicle named Bucanero, Italian for “black hole,” to hide its debt.

In Uber’s case, a program named Hell was only ever bound to be trouble. Newly appointed CEO Dara Khosrowshahi has a lot of things to do, but to play it safe he should probably fast-track a new Uber nomenclature. Go with something boring, like mountains. Or cities. Uber is in a lot of those, and project Miami rolls off the tongue a lot better than operation Hell in a deposition.

Low-value tech, high-value earrings.

What did you do in July and August? Anthony Levandowski tracked down a pair of earrings:

From 2011 to 2014, Seval Oz was head of Global Partnerships and Business Development for Google’s self-driving car program. When she left the company that August to run Continental’s Intelligent Transportation Systems division, Google threw her a going-away party at which it presented her with distinctive, custom-made earrings.

The nature of these earrings was revealed last week in a deposition of Pierre-Yves Droz, a long-time engineer on the self-driving team. A lawyer for Otto Trucking handed Droz the earrings and asked if he recognized them. “Those… are early version of the GBr2 transmit boards,” replied Droz.

Waymo, the driverless car maker spun out of Google, has spent months and a truly daunting number of pages of legal documents suing Uber for allegedly stealing trade secrets. A key part of its case has been emphasizing the confidentiality and security of the documents Levandowski reportedly downloaded before he quit Waymo and went over to Uber. So it’s not a great look for Waymo that a few years before bringing this case against Uber, it took a version of the top-secret designs that are central to its complaint and turned them into a pair of earrings.

Perhaps the earrings themselves were top secret. ENCRYPTED. MADE IN WAYMO HQ. POLISH GENTLY. WEAR ONLY AMONG COLLEAGUES. At any rate, Levandowski, who suddenly seems to have found out or remembered that these earrings existed, spent three weeks in July and August trying to obtain them, according to text messages included in court filings. “I could meet you in Fremont or do dinner your call,” he wrote Oz at one point. “Just want to make sure I don’t forget to grab the ear rings.”

Elsewhere, a Google engineer told a Google lawyer that the files accessed by Levandowski were “low-value” and don’t “ring the alarm bells for me.” “It’s all electronics design—schematics and PCB [printed circuit board] layouts—and the component library for their creation,” the engineer wrote. “It was considered low-value enough that we had even considered hosting it off of Google infrastructure.” If the lawsuit against Uber doesn’t work out, Waymo could always pivot and start an entire PCB-inspired jewelry line.

A messaging medium to millennials.

Meal-Kits Are Probably Overvalued, So Why Does Big Food Keep Buying Them? asks this article from Fortune. Unfortunately it doesn’t answer the question but it does quote Howard Waxman of Packaged Facts on kits as “a messaging medium to millennials with money to spend.” Not a message, mind you, but a messaging medium. My sample size is admittedly small but I am a millennial and I don’t know too many millennials with $60 a week to spend on a Blue Apron meal plan or $69 on Sun Basket or $72 on Purple Carrot and so on. (Clearly all that money is going toward boozy brunch and avocado toast—now available in “adult treehouses”!) What the millennials probably do want is the free or heavily subsidized trials they can get of meal kits, which might explain why retention rates on these services are so bad (“anti-stickiness,” to quote this professor on LinkedIn).

Who is still interested in Blue Apron? Lawyers!

That’s only the latest ones, there are many more. Blue Apron’s stock is holding steady at just over $5.

Other stuff.

Chinese-backed Taxify takes on Uber in London. Taxify forced to suspend London operations after just three days. Turo raises $92 million for car-sharing. Volvo acquires car valet startup Luxe. Stealth startup Zoox in funding talks with SoftBank. Airbnb “100% committed” to protecting Dreamers. Airbnb mulls $100,000 donation to SF small business group. Airbnb extends olive branch in San Francisco. Lyft brings in Jeff Bridges. Uber plans to electrify London fleet. Canadian Man Wrecks “Charming” Paris Pad. Former NFL lineman drives an Uber when he’s bored. SF cab company crowdfunds competition with Uber and Lyft. Taxi medallions drag owners into debt. Get Free or Discounted Food With Lyft This Month. Lyft ends “fake” tax deductions. Uber pledges $500,000 to DACA legal fund. Seattle’s Uber-Lyft union law delayed again. Can Lyft be the Android of self-driving cars? How Waymo cars learn to navigate tricky intersections. Google tries to make peace with Detroit. Cities line up for HQ2. Week one of Grubhub’s employment trial. Lessons from scaling Airbnb. McKinsey on the auto revolution. Good people, good things.