Not exactly the sharing economy, but I recently finished Disrupted, the Dan Lyons book about working at Boston-area software firm HubSpot, and it is very dark, very funny, and full of ironic exclamation points. I recommend it, if you like that kind of thing.

Unicorpses?

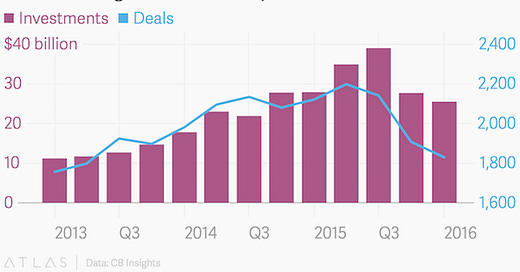

If you ever watched the first Harry Potter movie, perhaps you remember this scene, in which our young protagonist stumbles through a foggy wood to encounter a menacing, hooded figure exaggeratedly slurping the blood of a dead unicorn. I like to imagine that this is how Bill Gurley, a prominent venture capitalist who last week published a doom-and-gloom essay on the state of financing for billion-dollar tech companies, sees Silicon Valley. The essay is very good and I suggest you read it in full, but it can be summarized like this: The macro conditions in the Valley (record inflows to VCs, slowing investments to startups, and a totally stalled tech IPO market) have created an extreme funding climate in which startups that once happily subsidized fantastical growth with massive burn rates are now desperately struggling to secure new funding and ever-higher valuations to maintain said burn rates and fantastical growth. The result is that companies are accepting “dirty terms” such as guaranteed IPO returns and ratchets from “shark” investors that could very well destroy them in the long run, but at least for now will help them hit their fantastical financing targets. The investors are clearly Voldemort, but I’m unclear whether the companies are Quirrell, the unicorn, or both.

Elsewhere, Jessica Lessin of the Information thinks tales of dying unicorns are “greatly exaggerated.” And over at Bloomberg View, Matt Levine thinks this is just more evidence that “private markets are the new public markets” and says you could read the introduction of dirty terms “as a sign of the unicorn market’s maturity.”

Settling up.

Last year, a pair of US district judges issued two rulings that seemed destined to wreak havoc on the sharing economy, if not upend it altogether. In both cases—one against Uber, the other against Lyft—the judges wrote that they could not determine whether drivers were independent contractors or employees, and that the matter would have to proceed to trial. “The jury in this case will be handed a square peg and asked to choose between two round holes,” US district judge Vince Chhabria wrote for Lyft’s verdict, in a much-quoted line.

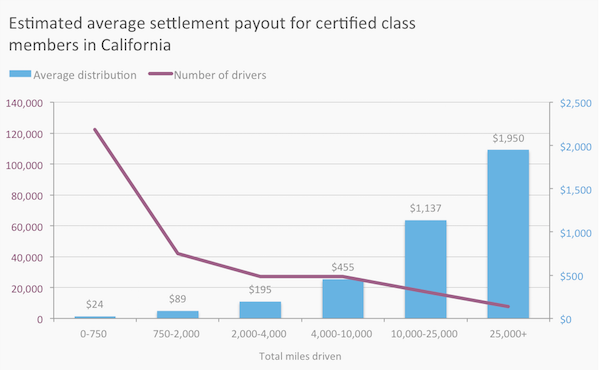

Thirteen months later, it’s looking like a jury will do no such thing. Lyft is attempting to settle and, in the landmark news of last week, so is Uber, which will pay up to $100 million to keep its drivers as contractors and wrap up class actions in California and Massachusetts. The phrase is “up to” because $84 million of that sum is guaranteed, while another $16 million hinges on Uber going public and, within a year of the IPO, multiplying its valuation 1.5 times from the current mark of $62.5 billion (look, a ratchet!). Twenty-five percent is going to attorney’s fees, while awards will be distributed to drivers based on miles worked. In California, the average payout for the most active drivers is nearly $2,000, which could double twice to $8,000 (if they opted out of Uber’s arbitration clause, and if only 50% of drivers claim). In Massachusetts, the top payout estimate is about half of that, according to court filings.

The settlement also contains a whole bunch of “non-monetary relief”—i.e., changes Uber has agreed to make to its service to better accommodate drivers. The biggest set of revisions comes on how Uber deactivates (read: terminates) drivers. Under the settlement, Uber is being forced to explain in writing what gets drivers kicked off the platform. Notably, drivers will no longer be deactivated for accepting too few rides. They’ll also be given at least two warnings before being removed, and be able to appeal Uber’s decisions. In addition to that, Uber will sanction a “driver association” which is explicitly “not a union” and “will not have the right or capacity to bargain collectively with Uber” but will “have the opportunity to meet quarterly with Uber management to discuss, in good faith, issues affecting Drivers and how Uber may address these issues.” Take that as you will. Lastly, Uber will clarify its rules around tips—namely, that they’re not included. Per the settlement, all aforementioned non-monetary relief will expire in two years.

Anyway, it’s a big settlement—“one of the largest ever” for workers claiming misclassification, according to the plaintiffs’ attorney—but my guess is that it’s also a good deal for Uber. One hundred million is expensive, but having its drivers deemed employees could have crippled Uber’s business. Suddenly, it would have to pay benefits for workers, guarantee them a minimum wage, and reimburse their on-the-job expenses (gas, maintenance, insurance, etc.). The settlement doesn’t rule on the employee v. contractors question, but it removes the imminent threat of a trial, and clears Uber to continue building provisions into US bills and regulations that sanction its independent contractor model. Could Uber have won at court? Perhaps. But instead it’s paying $84 million—maybe a bit more—to make it all go away.

Uber for failure.

Starring now in “death to Uber-for-X” is Shuddle, an Uber-for-kids service that shut down earlier this month because it ran out of money. Over at Mashable, Seth Fiegerman has a deep dive on what went wrong, and much of it is what you’d expect: subsidized growth, huge losses, a niche market that was nonetheless threatened by Uber. Also, though, employees who said stuff like this: “He didn’t do anything. He didn’t work on fundraising. He kind of was like this dad figure. He looked like a dad. We were like, ‘Perfect! You look like a dad, you’ll make a perfect face for this company that shuttles kids around.’” Good attitude! Bet that guy was popular with the parents.

Un-united.

Airbnb was reportedly in talks with the Service Employees International Union, one of America’s biggest unions, to endorse the Fight for $15 and to encourage its hosts to work with unionized home cleaners who earn at least $15 an hour. You might think this is a good development in the world of shady sharing economy jobs, but lots of people didn’t like it, because they felt Airbnb was using the SEIU negotiations to win favor for its many other political and regulatory battles. Also, Unite Here, a union that reps hotel workers, was not pleased. The deal has since fallen apart.

Other stuff.

“Will Ferrell will reportedly star in one of two Uber-themed movies.” Woz doesn’t trust Uber. Calgary mayor: “They are honestly the worst people in the world.” Gett’s revenue hits $500 million. Cabify raises $120 million. Uber adds live face checks. Massachusetts bill would restrict ride-hailing. Uber kills off instant food delivery in New York City. Lyft nixes 3X cap on surge pricing. The SEC is worried about unicorns. Theranos subject of criminal probe. Silicon Valley’s laundry bubble hasn’t burst yet. Munchery adds memberships. Uber and the Teamsters.

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can direct them to sign up here. Header art by Maddie Schuette, who is available for hire. Send tips, comments, and darkly funny book recommendations to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.