In non-strictly-sharing economy news, the Quartz tech team tried Soylent at the office yesterday. Spoiler: We didn’t like it.

The dirty secret of Airbnb.

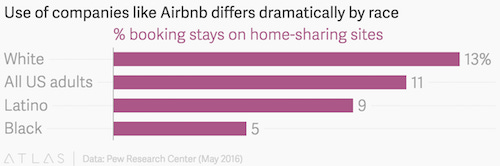

Is that it’s really, really white. I wrote a longish piece about this last week, which I encourage you to read. Alt hed: The Unbearable Whiteness of Airbnb’ing. It tries to synthesize a lot of what’s happened with Airbnb and discrimination in recent weeks. Here’s an excerpt:

Airbnb is no stranger to conflict. It is frequently accused of sidestepping hospitality laws by the hotel industry, which sees its home rentals as a growing business threat. It has clashed with entire cities on matters of data sharing, affordable housing, and short-term rental regulations. In such situations, Airbnb has proven adept at identifying common enemies—from hotel lobbyists to city policymakers—and mobilizing its vast base of users and hosts against them. Home-sharing, the company likes to say, “is both a community and a movement.”

Discrimination is different. It pits Airbnb hosts against Airbnb guests. It creates situations that are legally and ethically ambiguous, because most hosts aren’t professional hoteliers, but rather individuals choosing to rent out their private homes. It suggests that—contrary to all branding—the Airbnb community perhaps isn’t so diverse, and its home-sharing movement not really for everyone.

And a chart, for good measure.

Selling out?

Doug MacMillan reported Monday that Lyft has hired Qatalyst Partners, a boutique investment bank best known for helping tech companies get acquired. (Among other deals that Qatalyst has advised on: LinkedIn’s recent sale to Microsoft for $26 billion.) Frank Quattrone, Qatalyst’s founder and executive chairman, has per the Journal “contacted companies including large auto makers about acquiring a stake in Lyft.”

Lyft’s decision to hire Qatalyst could signal that it is pursuing a sale, or simply that it needs more money. For all that ride-hailing was pitched as an efficient, asset-light business, making it work has proven incredibly cash intensive as companies vie for both riders and drivers. Lyft closed a $1 billion funding round in January, but that money is going fast. The company is spending heavily to compete with Uber in the US, reportedly to the tune of $50 million a month. Uber, meanwhile, has sealed three new funding deals since the start of the year (including a record-setting $3.5 billion investment from Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund) and is said to be looking to raise as much as $2 billion from the leveraged-loan market. Small wonder if Lyft is struggling to keep up.

Upfront fares.

A couple weeks ago, I reported that Uber was quietly ending surge pricing as we knew it by replacing its signature multipliers—those bright blue numbers like 2.1x that consumers have grown to hate—with straightforward price quotes for each trip. Last week, Uber has confirmed that this is indeed the case. It’s branding the initiative “upfront fares” and the core promise seems to be something like “never do multiplication again.” (The actual tagline, in fact, is “no math and no surprises.”) In practice, little is changing. Prices will remain dynamic. Drivers will still see surge in their heat maps.

So what’s this mean for consumers? Uber, not surprisingly, thinks it’s a boon. The company argues that upfront fares are much more transparent than surge multipliers because, as previously stated, people are bad at math and now instead of needing to convert a multiplier into a final price, they are simply being given that final price.

Personally, I feel like this is missing the point. People have always been able get fare estimates on Uber rides if they wanted one, which were accurate within a few dollars. (Even during surge! No math required!) What surge multipliers provided was relative value. They warned you, “Hey, this trip is currently really expensive,” which is a useful thing to know. When prices are surging with upfront pricing, on the other hand, people will just see small text reading, “Fares are higher due to increased demand.” That to me seems less transparent! Yes, I know the final dollar amount, but I no longer have a good idea of whether it’s reasonable. Upfront pricing is good for, like, a box of pasta, because what you’re getting basically doesn’t change and so you know about how much it should cost. It’s much less informative for Uber rides, which are highly variable because of things like route, traffic, and time of day. Most people probably don’t have a good sense for how much the Ubers they book should cost. Surge multipliers warned them that a $44 trip might be a rip-off. Upfront pricing implies that they should trust the amount is fair.

Silicon Valley goes to Washington.

Here is a story from Elizabeth Dwoskin at the Washington Post about how startups are hiring chiefs of staff. It is set, rather delightfully, in “the private dining room of a Michelin-star restaurant in San Francisco,” where a group of such people have gathered to discuss the tech industry “between spoonfuls of caviar panna cotta and shots of liquid nitrogen gin and tonics”:

Silicon Valley likes to thumb its nose at Washington. Tech executives have long derided the nation’s capital as a place where good ideas go to die by a thousand regulatory cuts. But increasingly, one quintessential Washington institution is taking hold: the chief of staff. Its growth in many companies is reflective of the evolution of the start-up boom: Companies have gotten bigger, often very quickly, and they’re seeking more organization and hierarchy as a result.

Sharing economy companies in particular have seemed eager to take a page from Washington. Uber famously hired David Plouffe, Obama’s former campaign manager, in August 2014 to be “a leader for the Uber campaign.” Airbnb last August appointed Chris Lehane, a former Bill Clinton aide, its head of policy. Others, such as Lyft, Handy, and TaskRabbit, have built out their policy rosters, and rightly so. Many sharing economy startups happen to be great businesses because they are also clever regulatory arbitrages. Uber and Airbnb are the best examples, but they’re certainly not the only ones. To succeed in the long run, all of these companies need a lot of rules changed in their favor, and that means they need to be playing politics.

Elsewhere: Obama hints at a future in VC, and Silicon Valley is salivating.

Other stuff.

BREXIT. Instacart cuts hours for cashiers in New York. Airbnb Sues San FranciscoOver a Law It Had Helped Pass. Julia Child Foundation sues Airbnb. Uber files to operate in Sioux Falls. Uber brokers deal in Chicago. Uber awaits deal in Massachusetts. Uber’s Battle for China. Uber, Lyft settle lawsuit over top executives. Judge green-lights $27 million Lyft settlement. Another driver class action. What Uber drivers really make. A Cautionary Note on the Help Wanted Online Data. Uber’s and Tinder’s role in Brexit. Possible Names for EU Exits for All Members of the EU. Happened in an Uber. Happened outside an Uber. Uber for babysitters. Twilio IPO. Pizza robots. “We’re not trying to build a utopia for techies. This is a city for humans.”

Thanks again for subscribing to Oversharing! If you, in the spirit of the sharing economy, would like to share this newsletter with a friend, you can direct them to sign up here. Header art by Maddie Schuette, who is available for hire. Send tips, comments, and never Soylent to oversharingstuff@gmail.com.